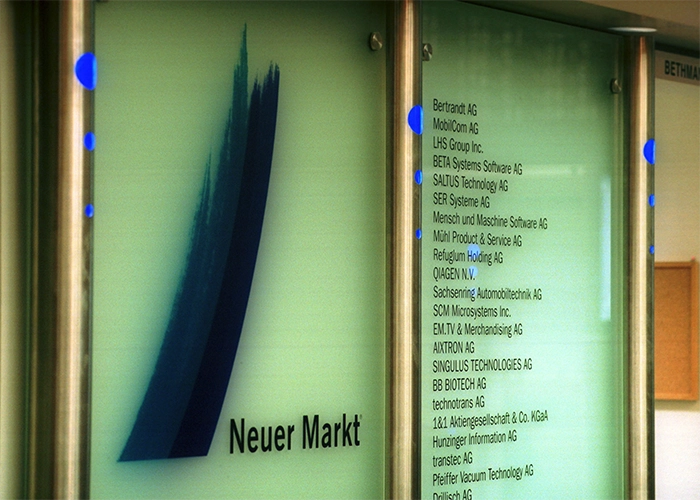

In 1999, the stock market was ablaze with excitement: the Nemax 50, the leading index of the Neuer Markt (a segment of the Frankfurt Stock Exchange created for high-growth, high-tech companies, similar to the NASDAQ in the U.S.), made its debut. This period marked an era of fervent enthusiasm, with the dream of rapidly accumulating wealth through stock gains drawing many to invest, their imaginations captivated by the burgeoning possibilities of mobile communication and the internet.

Optimism Unchecked by Reality

There was a prevailing sentiment that the digital revolution’s surge in innovation could somehow bypass traditional economic cycles, rendering recessions obsolete. Towards the end of the 1990’s, this optimism led to a startup boom in Germany, where nearly every idea related to new media or the internet received funding, with investors and corporations eagerly backing these nascent companies in anticipation of rapid growth. Expectations of quick growth overrode rational caution.

Germany’s Startup Mania

Taking inspiration from the American Nasdaq’s record-breaking performance, the German Nemax aspired to replicate this success. Indeed, initial expectations were met when the Nemax 50 hit an all-time high of 9,631.53 points on March 10, 2000. Government statistics highlighted the registration of around 300,000 “innovative, business-related service companies” at the millennium’s turn, facilitated by the expansion of necessary infrastructure like high-speed internet. Many of these start-ups simply relied on the digital transformation of “old economy” business models.

The Bursting of the Bubble

Skeptics of the market’s irrational exuberance were few and far between. Stock market expert André Kostolany, for example, voiced his concerns as early as 1998 on an NDR talk show, calling the new economy a “scam with marked cards and cheats.” The inflated valuations of dotcom companies, which propelled their stock prices, lacked grounding in solid economic fundamentals. This disconnect led to the Nemax’s dramatic collapse. From being valued at 235 billion euros in 2000, the companies on the Neuer Markt plummeted to less than 30 billion euros by 2002, as their ambitious growth projections failed to materialize.

A Tenuous Edifice of Market Fantasies

The case of Daniel David, a pop singer turned entrepreneur, illustrates this folly. On August 11, 1999, the day of a total solar eclipse, his company Gigabell went public. Despite heralding a new dawn for his company during its launch party, Gigabell, which started as a simple internet provider and operated at a loss, soared to a market valuation of 800 million euros without ever turning a profit. In November 2000, Gigabell was insolvent and was the first company to be excluded from the Neuer Markt. It declared bankruptcy in November 2000, becoming the first company to be delisted from the Neuer Markt. Other firms resorted to fraudulent financial reporting and deceptive announcements to maintain their facade for a time.

Failed business plans led to the collapse of over-hyped companies not just in Germany, but globally, catching inexperienced investors off guard with their rapid downturns. Many missed the chance to sell their shares in time, suffering significant financial losses. Similarly, the American Nasdaq took a dramatic plunge, falling from 5,048 points on March 10, 2000, to just 1,114 points by October 9, 2002.

The Legacy: A Surge in Innovation

Despite the market crash wiping out numerous companies and vast sums of investor money, the march of the internet and digitalization remained unstoppable. Today, giants like Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon demonstrate the enduring impact of the new economy, having revolutionized both our personal and professional lives.