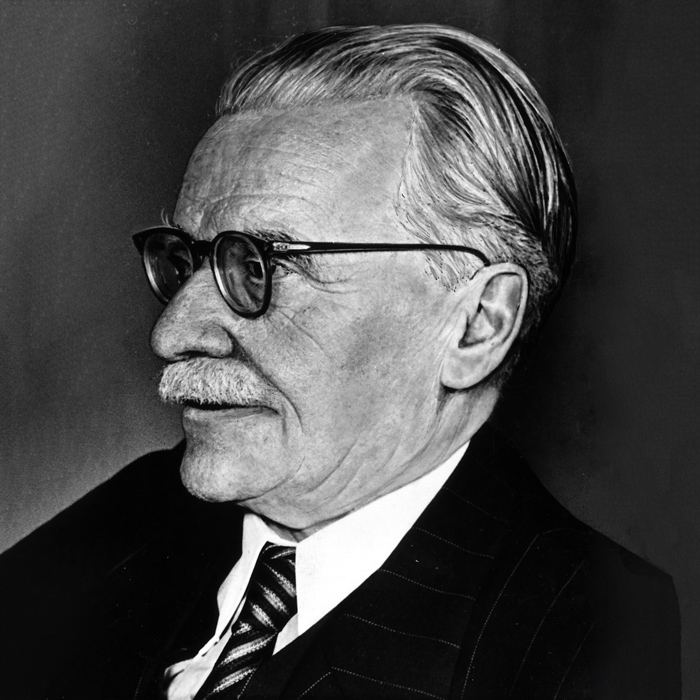

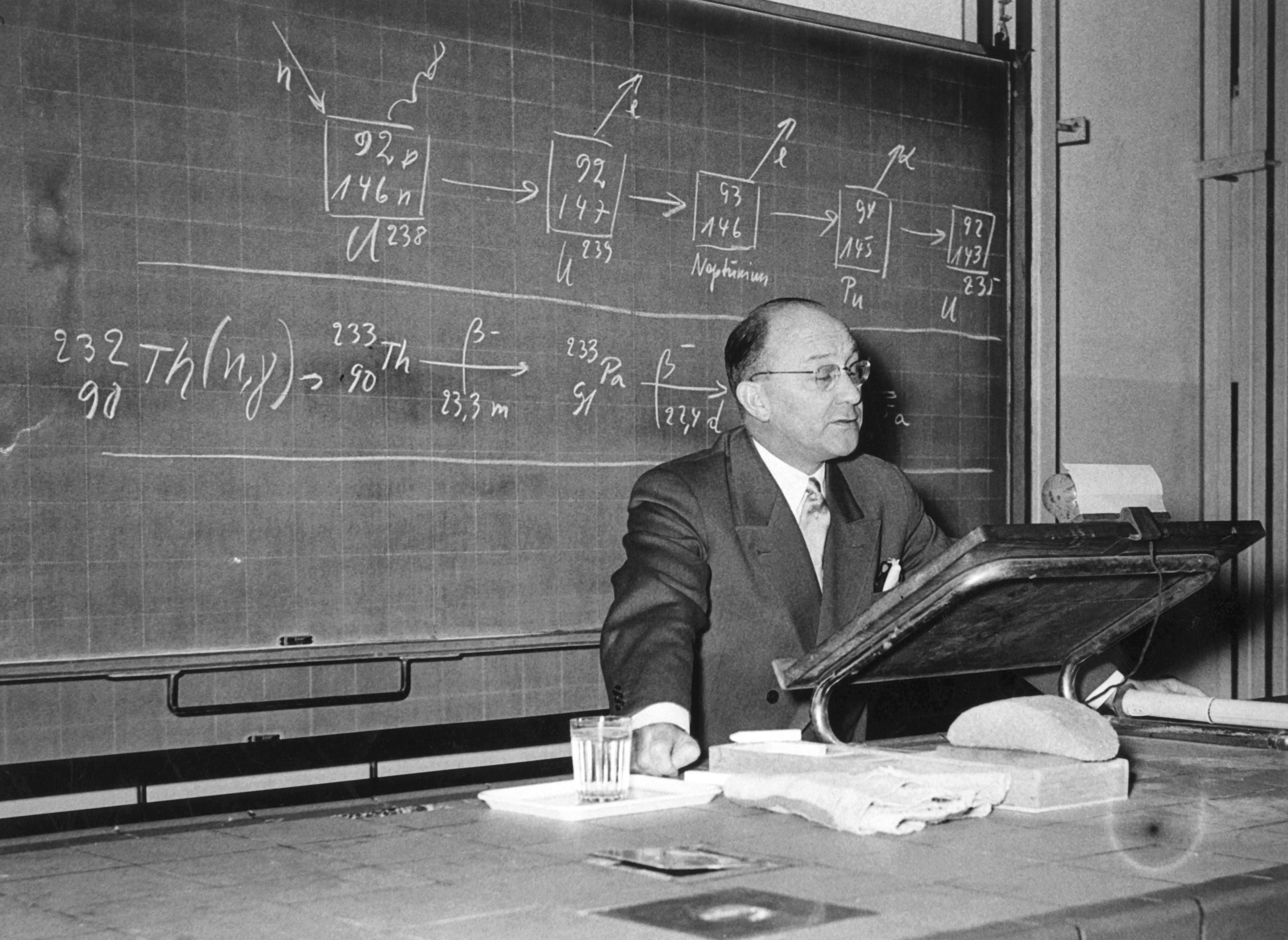

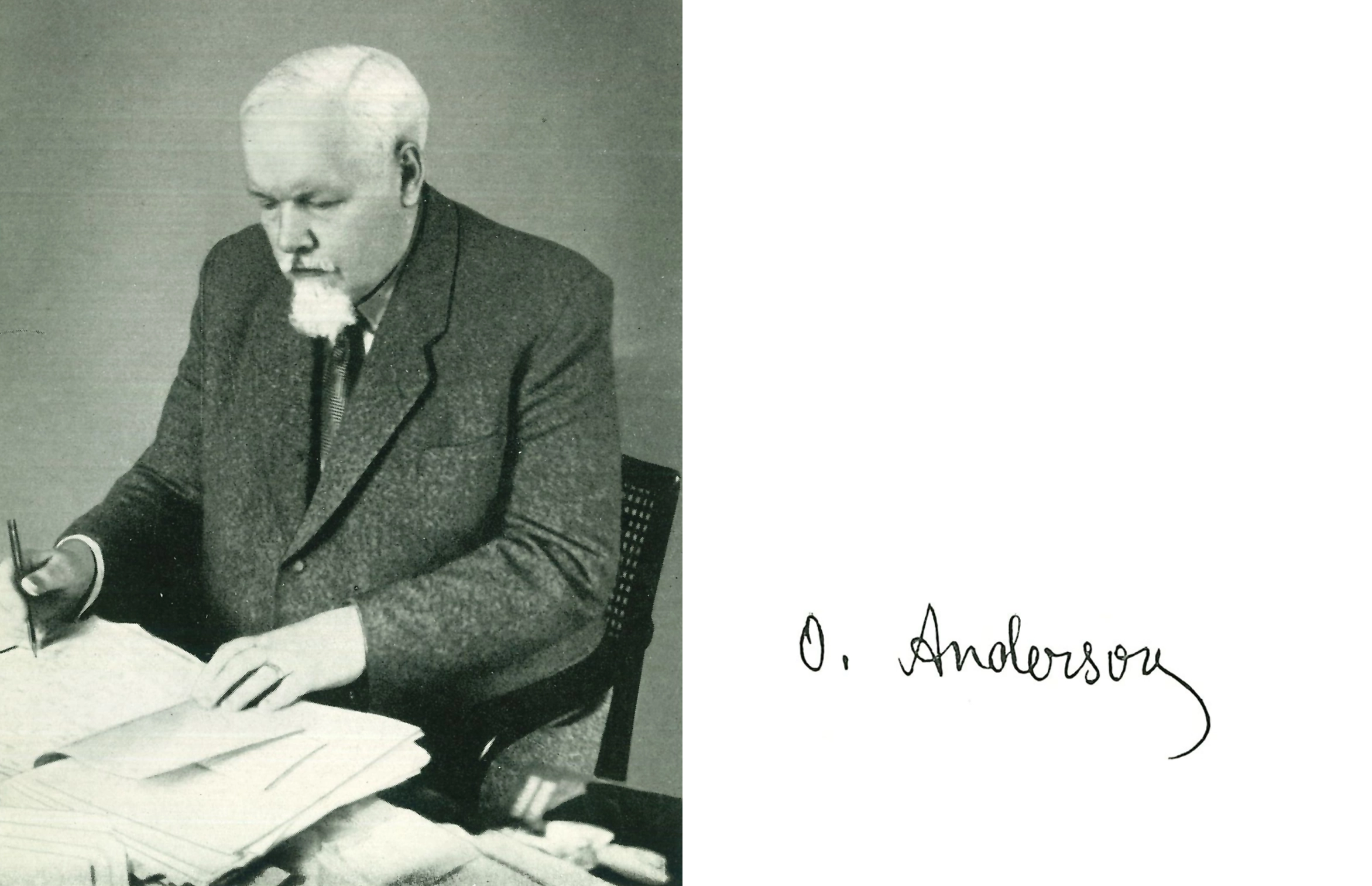

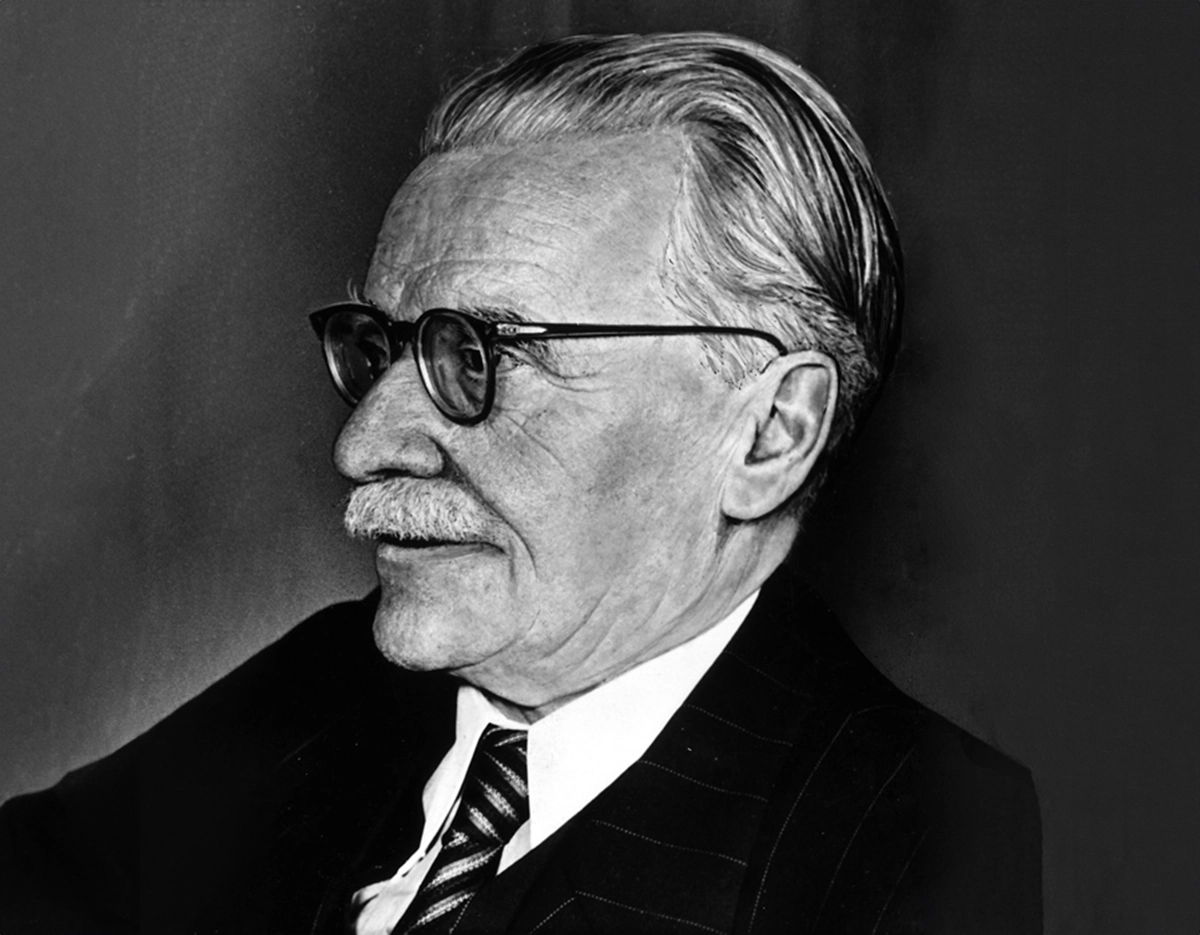

Adolf Weber: Pioneering Influence at the ifo Institute

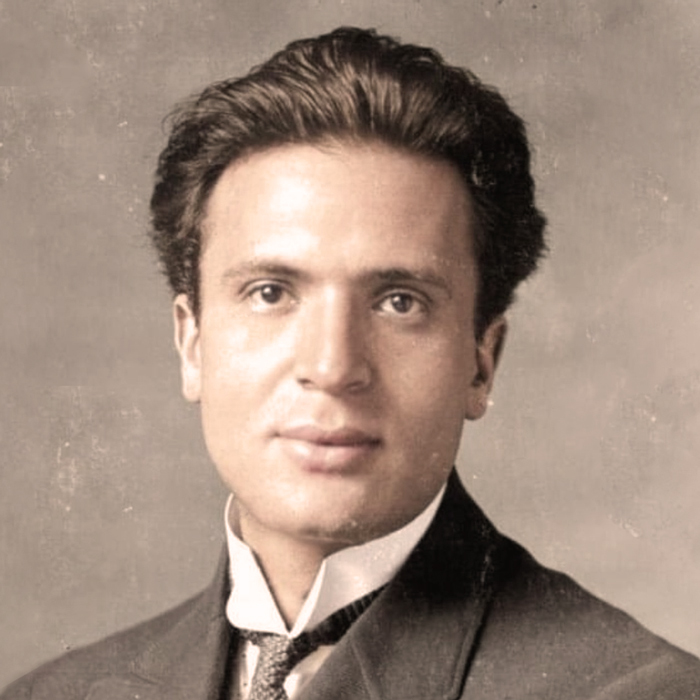

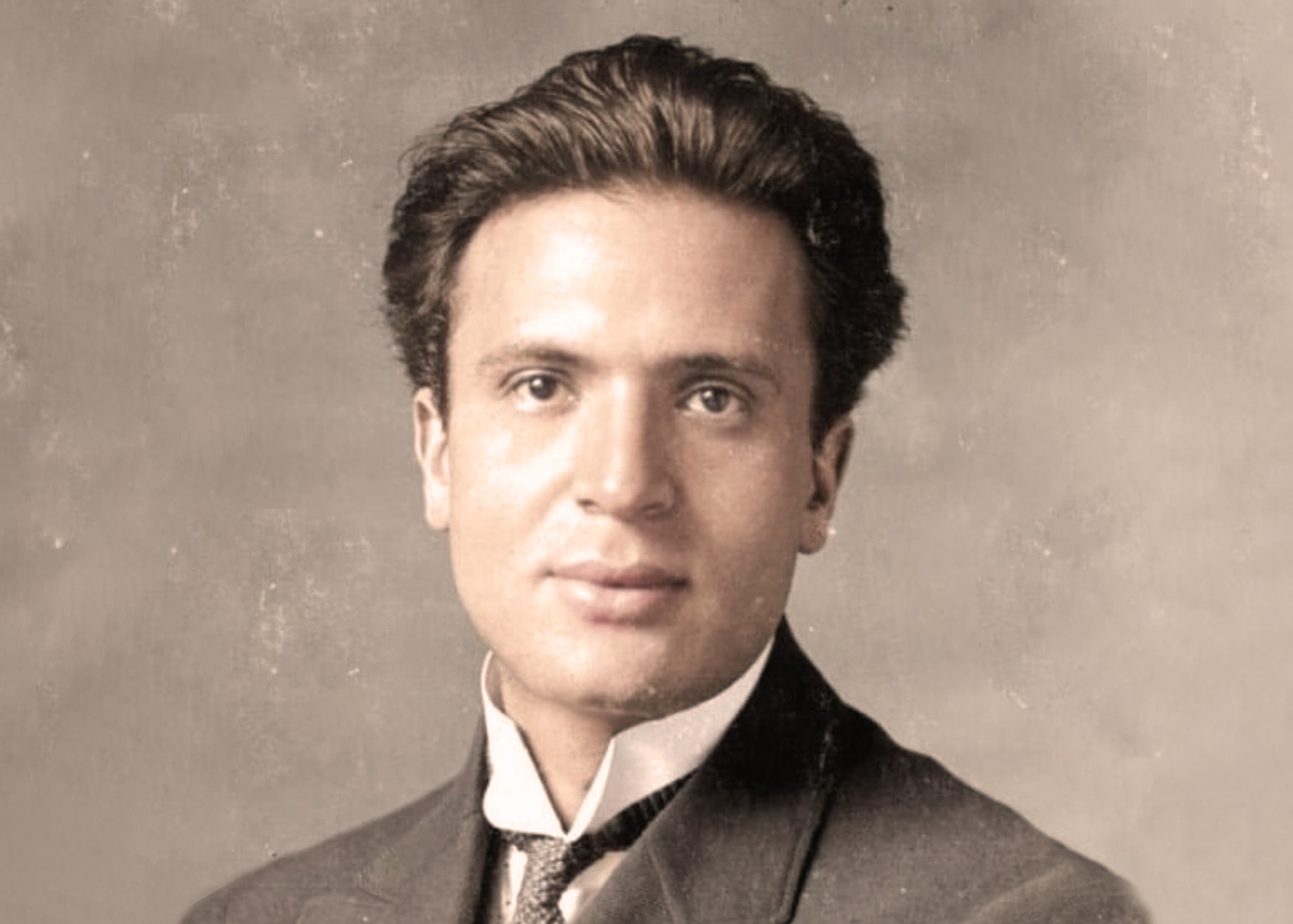

Adolf Weber was one of the most influential German economists of the 20th century and a prominent figure, not only within the Faculty of Political Economy but also across the entire University of Munich. His legacy is honored at the ifo Institute in Munich, where since 1999, the main office building at Poschingerstrasse 5 has been named in his honor.

Education and Early Academic Career

Born in 1876 in Mechernich in the Eifel region, Weber began his studies in law and political science in Bonn, where he earned his doctorate in law in 1900. However, his true passion lay in economics, and just two years later, he completed a second doctorate in this field at the University of Bonn. His first major academic appointment came in 1908 at the Commercial College in Cologne, where he quickly rose to lead the College for Social and Municipal Administration.

A Distinguished Professorial Career: From Wroclaw to Munich

Weber’s academic journey took him from Wroclaw, Poland between 1914 and 1919, to Frankfurt am Main from 1919 to 1921, and finally to the University of Munich. There, from 1921 to 1948, he held the Chair of Economics and Finance, and authored influential textbooks on general economics, trade, and transport policy, which reached high print runs. His research covered a wide range of topics, including social policy, banking, land reform, housing, and foreign trade.

Strategies for Post-War Economic Reconstruction

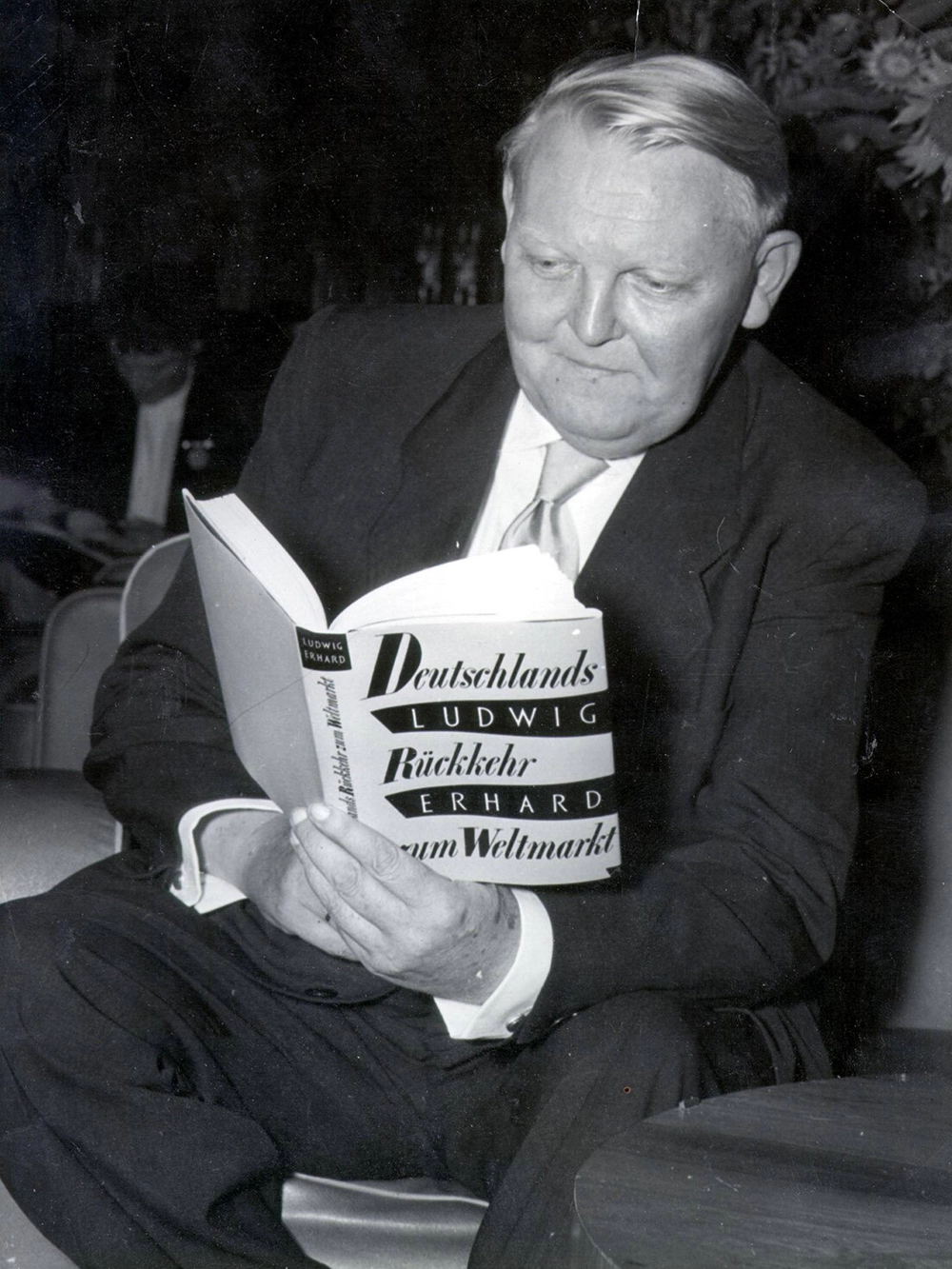

During World War II, Weber critically analyzed both the Soviet planned economy and the Nazi command economy. Following the war, he established the “Economic Working Group for Bavaria” in Munich, bringing together leading figures from academia and practice to pool economic knowledge for the country’s reconstruction. After stepping down as Bavarian Minister of Economic Affairs, Ludwig Erhard collaborated closely with Weber in this group. Together, they laid the groundwork for applied, politically-oriented economic research in Munich, which allowed the ifo Institute to thrive from 1949 onwards.

To emphasize its independence from political parties, the working group was affiliated with the Department of Political Economy at the University of Munich, under Weber’s leadership. The group’s activities resulted in numerous publications on economics and economic policy. Weber himself published the memorandum “Transition Economy and Monetary System” in 1945 and followed up with the essay “Where Is the Economy Heading?” in 1946. Thanks to his exceptional expertise, Weber became one of the most influential advisors to the Bizonal Economic Administration, which was responsible for managing the British and American occupation zones.

Economic Philosophy and the Munich School of Economics

Weber was not only a leading economist but also a charismatic teacher and founder of the Munich School of Economics. Rooted in the liberal economic traditions of the German Empire (Kaiserzeit), he advanced a “dynamic business cycle theory,” explaining economic crises not as inevitable outcomes of cyclical economic laws but as the result of overinvestment in relation to national savings. While the production of consumer goods remained relatively stable, irregularities in the production of capital goods triggered economic downturns. Weber argued that economic policy should focus on ensuring long-term capital formation by companies through real savings rather than excessive borrowing.

Adolf Weber and Ludwig Erhard: Key Figures in the Foundation of the ifo Institute

Following his time as Bavarian Minister of Economic Affairs, Ludwig Erhard — now head of the Institute for Economic Observation and Economic Consulting, as well as the South German Institute for Economic Research — continued his close collaboration with Adolf Weber. This partnership during the challenging post-war years helped foster a robust environment for applied, politically-oriented economic research in Munich, which laid the foundation for the ifo Institute’s success from 1949 onwards. Adolf Weber passed away in Munich on January 5, 1963.

People

Alfred von Heymel: Publisher, Patron of the Arts, Bon Vivant.

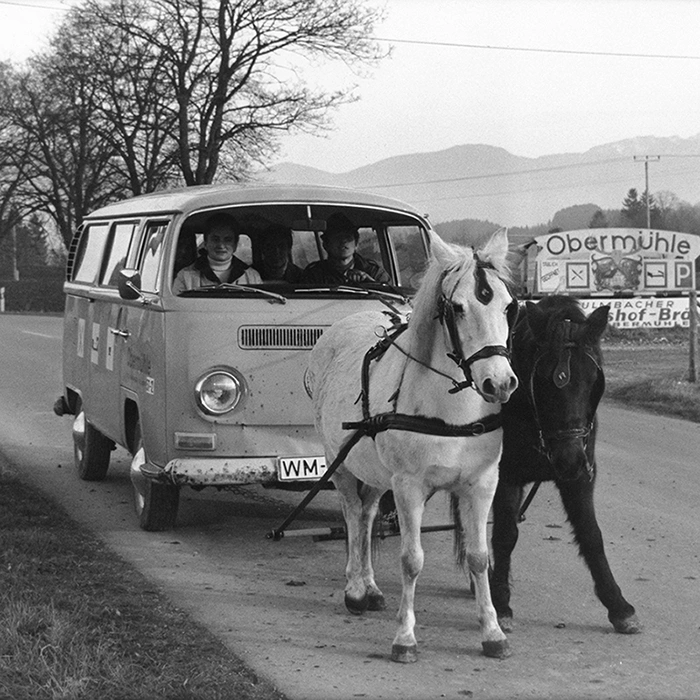

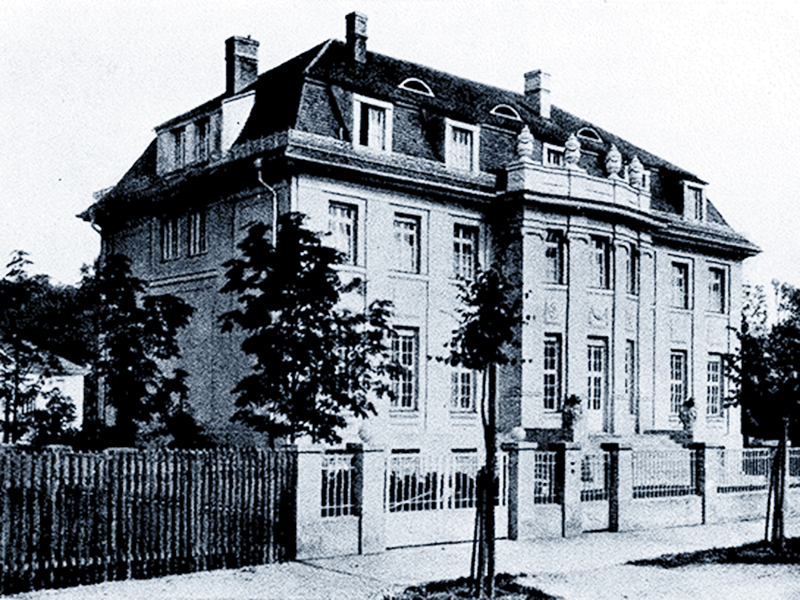

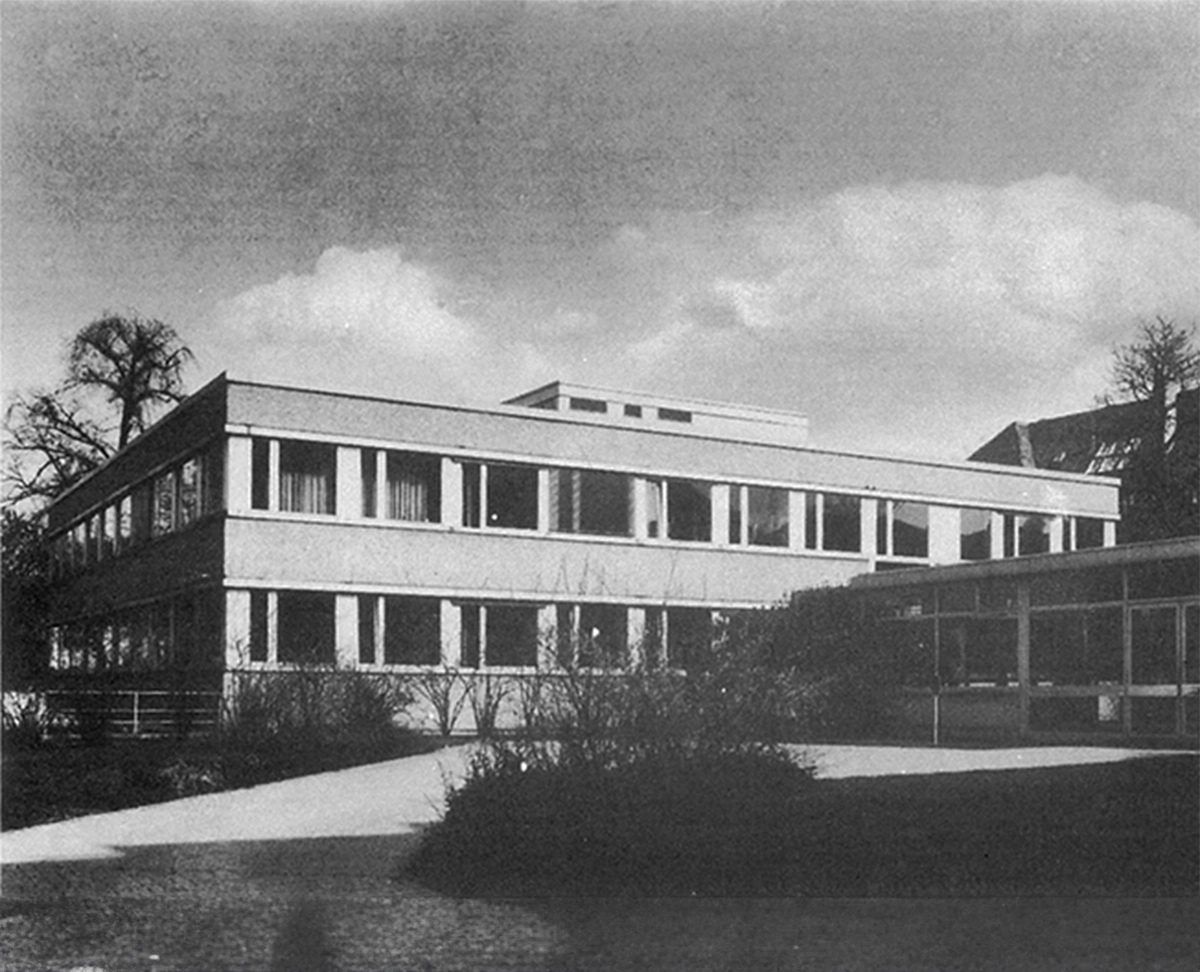

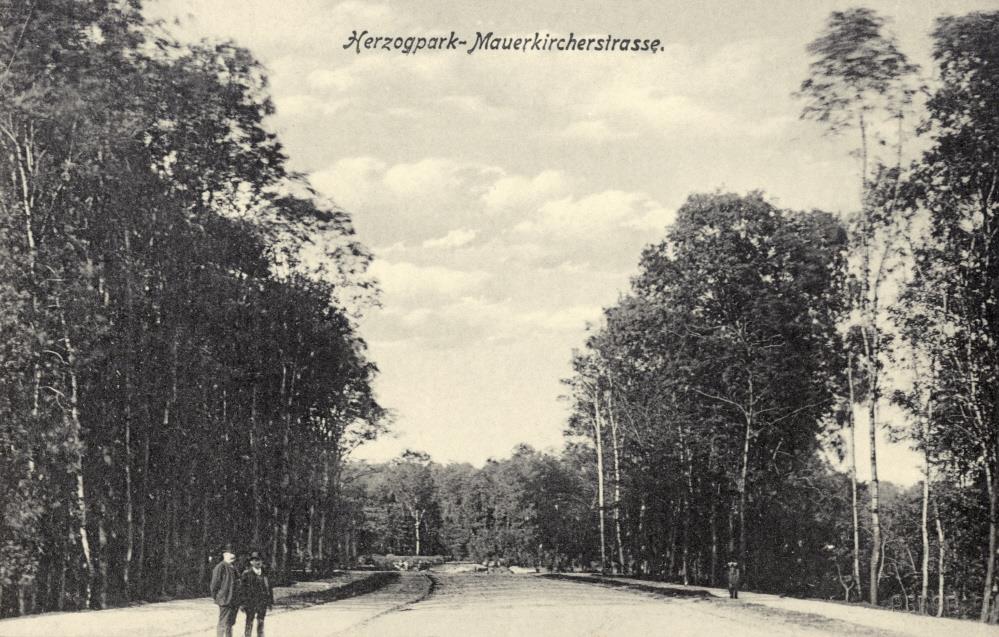

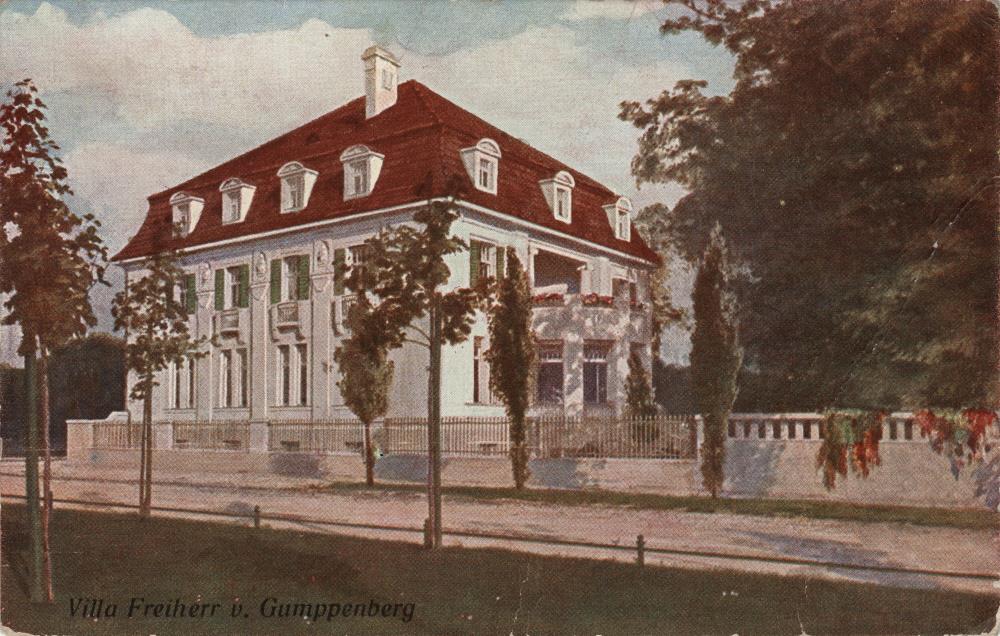

Munich, 1909: What does a well-known bon vivant do when he comes into a fabulous inheritance? He buys an exclusive 4,400 square meter plot in Herzogpark for 96,000 German marks and commissions on of the city’s most sought-after architects, Karl Stöhr, to build an opulent neoclassical-style house for him for another 180,000 marks. Fast forward to today, the impressive building at Poschingerstrasse 5, which was completed in 1910, is now home to the ifo Institute. Its first owner, Alfred Walter von Heymel, was indeed a colorful personality.

“Beautiful Women, Beautiful Horses, Beautiful Flowers ...

... English books in supple leather bindings, lots of good food and drink, accompanied by a host of friends, some closer than others – this was how the young men from Bremen, Alfred von Heymel and his cousin Rudolf Alexander Schröder, spent their days and nights,” described writer Rolf von Hoerschelmann, painting a vivid picture of their lifestyle.

“Die Insel” – A Beacon of Literary Modernism in Germany

Heymel’s most important patronage was the literary magazine “Die Insel”, which he founded together with Rudolf Alexander Schröder in 1899. Contributors included literary greats such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Rainer Maria Rilke and Robert Walser and the illustrations were by none other than Heinrich Vogeler.

Rolf von Hoerschelmann reminisces, “It featured modern poems, literary gems from all eras and countries, and witty essays, all printed on heavy floral paper and bound in exquisite designs, thanks to its connection with the Insel Verlag book publisher.” This book publisher, also founded by Alfred von Heymel and Rudolf Alexander Schröder in 1901, still exists today, unlike the magazine, which ceased publication just three years after its founding. There were simply too few buyers and the financial burden eventually became too much for even a wealthy patron like Heymel to bear.

The End of a Magazine, The Start of a Dramatic Life

In 1904, von Heymel married Gitta von Kühlmann, a “blonde aristocratic beauty,” as von Hoerschelmann puts it. In 1910, the couple moved into their new villa at Poschingerstrasse 5, but the marriage failed. Seeking a fresh start after his divorce, von Heymel travelled extensively in Africa before settling in Berlin in 1912, where he died two years later after suffering from tuberculosis.

From the 1920s, the consulates of the then Kingdom of Siam and Argentina, among others, resided in the Villa Heymel. The first employees of what is now the ifo Institute moved into the imposing building in 1952. If you take a walk through Bogenhausen district, you can see it up close.

Note: For the sources used in this text, click on the imprint.

People

Local History

Artificial Intelligence: Opportunity or Danger?

It is undisputed that the use of artificial intelligence is changing society, especially the world of work. However, there is great uncertainty about the “how.” Is its use more of an opportunity or more of a threat? On the one hand, there are expectations of greater efficiency, dynamism, and new business models. On the other hand, there are fears associated with these opportunities – for the economy as well as for society. Will AI become a job killer? Will AI even become uncontrollable due to its lack of traceability? A suitable framework for dealing with AI technologies is essential.

AI, Cloud Computing, and Blockchain – Where Does the German Economy Stand?

Digital technologies are not only changing the efficiency and flow of production processes. They are also having a profound, disruptive impact on our economy in a process often called “digital transformation.” This digital transformation refers to the integration of digital technologies into economic workflows, as well as their impact on living conditions and society as a whole.

The numerous new technologies that have seen considerable progress and widespread acceptance in recent years include digital platforms, the Internet of Things (IoT), robotics, cloud computing, blockchain, and, last but not least, artificial intelligence.

Their wide-ranging application and far-reaching dissemination are giving rise to innovative products, services, and business models that are used in a variety of industries, from logistics and energy to agriculture, trade, telecommunications, financial services, manufacturing, and healthcare. They even have the potential to change people’s lives and society in the long term.

All three technologies have the capacity to significantly change existing business models and the way in which knowledge, products, and services are created and exchanged.

ChatGPT Brings AI to the Center of Society

AI-based systems use techniques such as machine learning and deep learning to automate complex tasks such as pattern recognition, language processing, trend analysis, and decision-making with the help of large amounts of data. Increased computing power, the availability of large amounts of data, and new algorithms have led to the rapid development of AI technology and enabled its broad application across all economic sectors. Most recently, the spread of chatbot applications, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, has brought AI to the forefront of public interest.

AI in Companies: HR Managers Have Concerns about Its Use

Fully 86 percent of German HR managers have concerns about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in their company. This is according to the latest Randstad-ifo Personnel Manager Survey. The most common reason given by HR managers was a lack of expertise (62 percent). Legal aspects are an issue for 48 percent. A lack of trust in AI was cited by 34 percent. For one-quarter of HR managers, a lack of acceptance is an obstacle to the use of AI. For 22 percent, no added value is evident from AI. The high cost of AI is viewed critically by 19 percent, high costs by 18 percent.

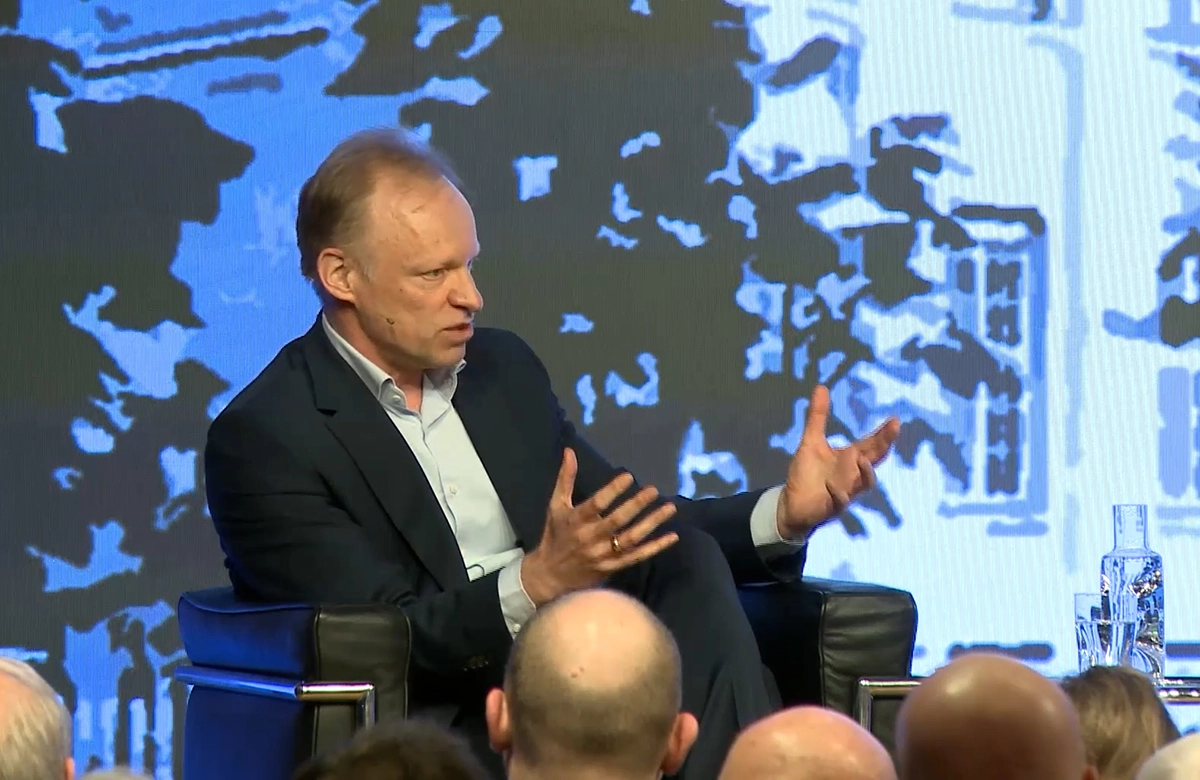

AI Takes Center Stage at the Munich Economic Debates (MED) 2024

At the Munich Economic Debates (MED), we continuously explore the profound impact and burgeoning potential of artificial intelligence (AI) across various sectors. Throughout the year, we bring together leading experts from academia, industry, and society to delve into the vast opportunities and challenges presented by this transformative technology. To stay updated on event schedules and access livestreams, visit our ifo website. We invite you to join the conversation and help shape the dialogue about AI’s role in shaping our future.

Events

Impulse

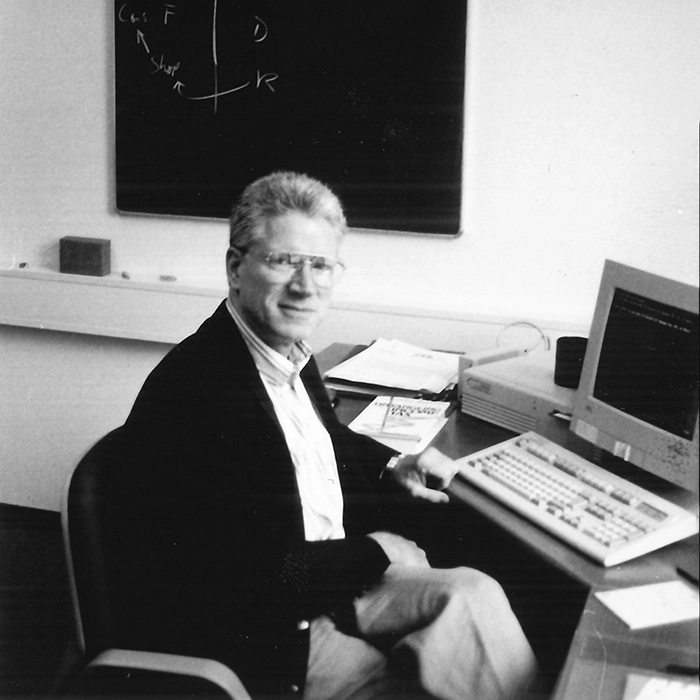

Big Data Economics at the ifo Institute

Big data – a buzzword: What does it mean for economics? How do you make masses of unstructured data usable for economic research? Sebastian Wichert is the director of the LMU-ifo Economics & Business Data Center, or EBDC for short. In the ifo podcast “Economy for All”, he provides insights into his work with big data economics and the significance of his department within and outside of ifo.

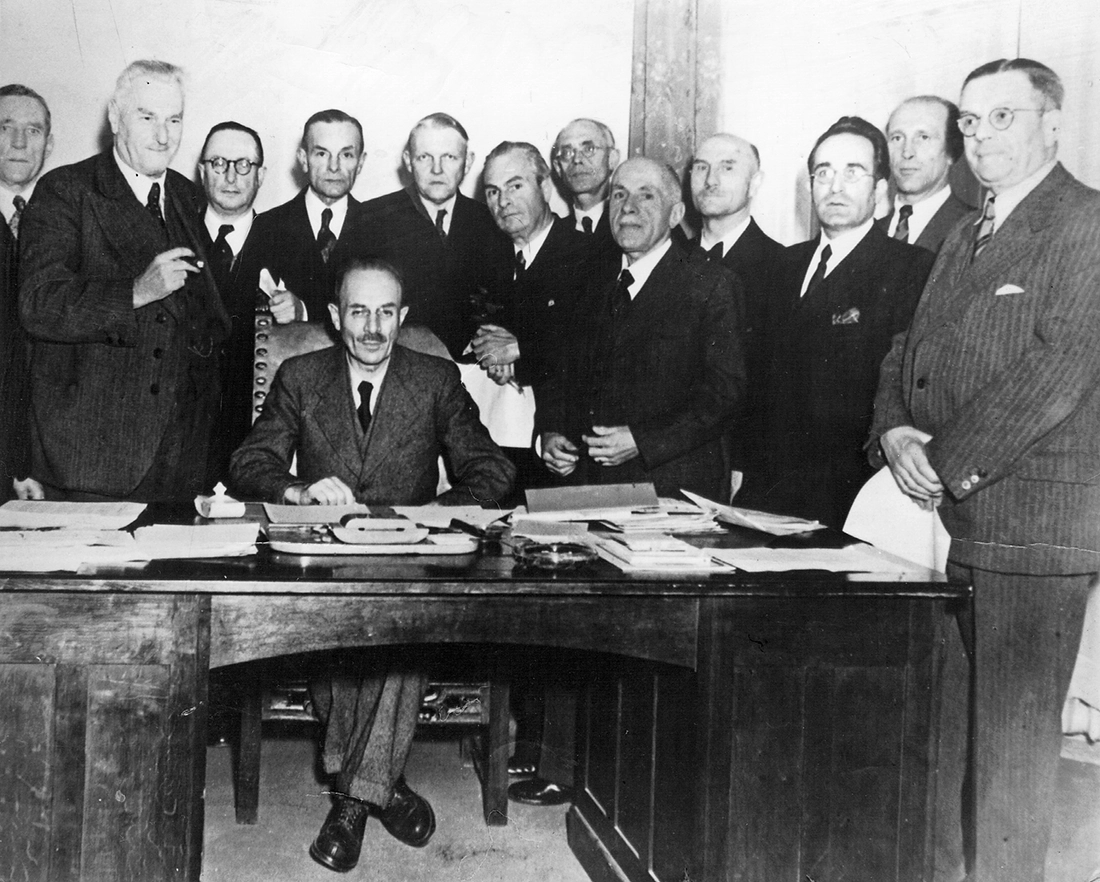

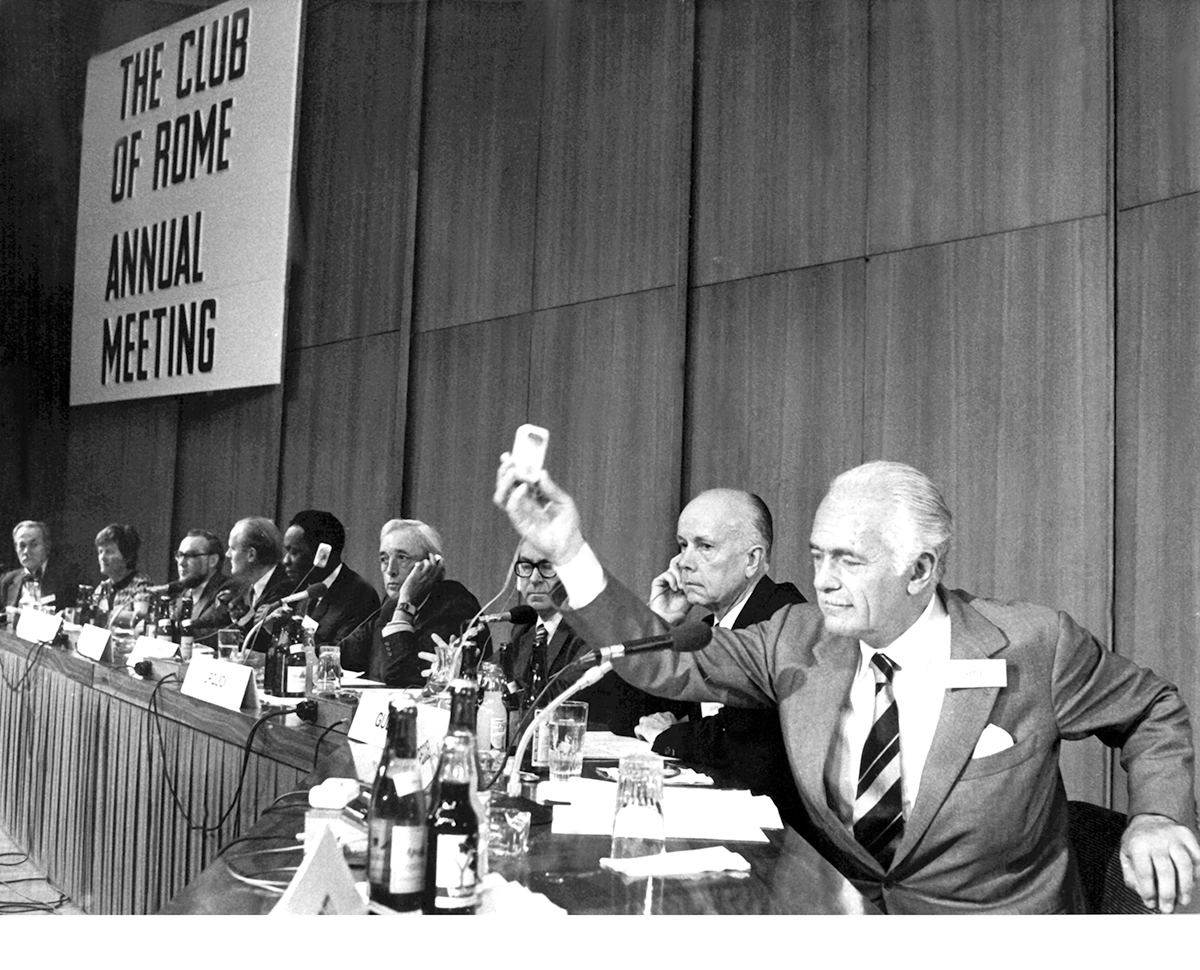

Board of Trustees and Administrative Council: From the Inaugural Meeting to Today

From the outset, the Board of Trustees and the Administrative Council played a decisive role in the development of the ifo Institute. On January 24, 1949, the inaugural meeting adopted the Institute’s Bylaws. The role of the two bodies, then still called the Board of Trustees and the Administrative Committee, is defined as follows: “The Board of Trustees shall support the Executive Board in the fulfillment of its tasks.” And further: “It shall make use of an administrative committee and the Research Advisory Board to carry out its tasks.” 75 years have passed, and definitions and tasks have changed. A look back and at current activities.

Ludwig Kastl – Chairman From the Very Beginning

The Administrative Committee was a body that was assigned to the Board of Trustees. Ludwig Kastl, who Ludwig Erhard had already recruited for the position of Chairman of the Board of Trustees in 1946 when he founded his Institute for Economic Observation and Consulting, was the first to chair the Administrative Committee and the Board of Trustees.

Kastl had begun his career as a civil servant in the Colonial Department of the Foreign Office and worked in German South West Africa from 1906 to 1920. After returning to Germany, he left the civil service in 1925 and became a managing member of the Presidential Board of the Reich Association of German Industry. After the RDI was ‘brought into line’ by the National Socialists in 1933, Kastl was forced to resign because of his Jewish heritage. During the Second World War, he worked as a lawyer. After the war, and with a clean political record, he took on a leading role at MAN in Nuremberg, and between 1946 and 1947 was President of the Bavarian Economic Council.

His extensive professional experience and large network in politics, business and society made him extremely valuable to the ifo Institute and one of the central figures in its foundation and development. He remained active on the Board of Trustees of the ifo Institute until 1962, when he retired from all offices at the age of 84.

The Board of Trustees: A Strong Network

The composition of the Board of Trustees was clearly defined in the ifo Institute’s founding statutes in 1949. Its aim was to establish contact with the Institute’s most important stakeholders from business, academia, politics, and public administration, and thus network the ifo Institute with key social groups. As it primarily had to elect the members of other statutory bodies and committees and perform support tasks, only natural persons were represented here. Neither has changed to this day.

The tasks of the Board of Trustees were to elect the Board Council, the Executive Board and the Research Advisory Board, and “support the Executive Board with regard to the purpose of the association”. The position of the Chairman was further strengthened by assigning him not only the chairmanship of the Board Council but also the chairmanship of the Research Advisory Board and the members’ meetings.

Administrative Council – A Key Role

In 1956, following an amendment to the bylaws, the Administrative Committee became the Administrative Council and an independent statutory body. As was already the case since the adoption of the founding statutes, key strategic management decisions were made here. In addition to personnel policy issues, this included responsibility for finances, which was divided during the ifo Institute’s start-up phase between the Administrative Committee and the Executive Board. The Administrative Committee also approved the budget, was responsible for procuring the approved funds, and audited the financial statements. In the early years of the Institute, the Chairman of the Administrative Committee, Ludwig Kastl, thus had prominent responsibility for ifo’s finances. His position was even strengthened further with the amendment to the bylaws in 1956, when he was assigned the chairmanship of the Research Advisory Board and the members’ meetings.

The New Beginning in the 1990s

Following the extensive reorganization of the ifo Institute in the 1990s, the Institute’s bodies and their functions were also redefined. The position of the Executive Board was strengthened as a steering body with overall responsibility for the development of the institute, and this increase in power was balanced by the expansion of the supervisory and advisory functions assigned to the other ifo bodies.

The Board Council was replaced in 1997 by the Administrative Council. The latter was authorized to appoint and dismiss the Executive Board members, and has a supervisory and advisory role vis-à-vis the Executive Board. In order to ensure the supervisory function through efficient work in a manageable group, the new bylaws limited the number of members of the Administrative Council to eleven. The responsible departments of the German Government and the Free State of Bavaria as well as the Faculty of Economics and the Faculty of Business Administration at LMU were each granted the right to appoint a representative to the Administrative Council. Other members of the Administrative Council who were appointed from the outset were the Chairman and Deputy Chairman of the ifo Board of Trustees and the Chairman of the Scientific Advisory Council. The remaining four members of the Administrative Council were elected by the members’ meeting.

The Bodies of ifo Today

Essentially, the tasks of the ifo Institute’s bodies have not changed: The Administrative Council has a supervisory and advisory role vis-à-vis the Executive Board. It consists of the Chairperson of the Board of Trustees and their deputy, a professor from the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration at LMU Munich, a representative of the federal government department and the department of the Bavarian State Government, the Chairperson of the Scientific Advisory Council, and up to five further members elected by the members’ meeting. The term of office of the elected members of the Administrative Council begins on July 1 of the year of election and lasts three years. Since 2023, Nina Hugendubel, Managing Partner of the book retailer H. Hugendubel in Munich, has been Chairperson of the Board of Trustees and the Administrative Council, with Christine Bortenlänger elected as her deputy.

People

Brexit 2016: A Shocking Turn of Events and Its Consequences

Britain‘s relationship with the European Union has always been at arm‘s length. In the 2016 Brexit referendum, 72.2% of eligible voters participated, with 51.9% voting in favor of leaving the EU. This event marked the United Kingdom as the first country to exit the EU, leading to immense economic consequences, according to the ifo Institute. After a year of intensive negotiations, a new trade and cooperation agreement between the EU and the UK was enacted in 2021.

The Road to Brexit: A Closer Look

Brexit promised better control over immigration, an end to payments to the EU, and full sovereignty for the UK. Conversely, there were warnings that leaving the single market could jeopardize the economic stability of the island. Politicians from various camps engaged in heated debates – in parliament, newspapers, talk shows, and on social media. The sentiment for Brexit was already noticeable in 2014 when Prime Minister David Cameron announced his intention to renegotiate the UK’s treaties with the European Union. Following the Conservative Party’s election victory under Cameron in 2015, the Brexit referendum was scheduled for 2016. Cameron also negotiated further special arrangements for the UK in the EU, contingent on the vote against Brexit.

The United Kingdom Divided

The Brexit referendum results laid bare the deep divisions within the United Kingdom. In England and Wales, the majority voted in favor of Brexit; however, in Northern Ireland and Scotland, as well as among London’s electorate, the majority voted to remain in the EU. The divisions were not only regional but also generational. A significantly larger proportion of young Britons voted to stay in the European Community compared to their older counterparts. In November 2018, Theresa May, David Cameron’s successor, reached a provisional withdrawal agreement with the EU. The final exit, initially planned for March 29, 2019, was postponed to April 12 and ultimately to October 31. The complexity and lengthiness of the negotiations between the parties proved too great.

The Protracted Conclusion

Facing heavy criticism from the public and her own party, Theresa May announced her resignation in the summer of 2019. Her successor, Boris Johnson, braced the nation for a hard Brexit with no agreements in place. However, after the British parliament passed a law against a no-deal Brexit, the EU postponed the exit date once again to January 31, 2020, when it finally occurred. A trade agreement, which also included a free trade deal, was still absent. After lengthy negotiations, it came into force on January 1, 2021. While bilateral trade now enjoys exemption from customs duties, UK exports are subjected to extensive customs formalities. Further cooperation agreements were signed in areas such as crime fighting, climate policy, and energy supply, ensuring that collaboration in critical areas continued and the UK was not completely severed from the EU.

Economic Consequences of Brexit

As opponents of Brexit predicted, the negative economic consequences have been less severe for EU countries than for the UK. By 2021, the UK had fallen from being Germany’s third most important trading partner in 2015 to tenth place. In 2022, the ifo Institute updated its initial study on Brexit’s consequences from 2017. Key findings include:

• Since the Brexit referendum on June 23, 2016, the British pound has depreciated by around 13%.

• German exports of goods to the UK have dropped in nominal terms from 90 billion euros to 84 billion euros since 2016.

• In many sectors, the UK’s share of German imports and exports has decreased significantly, particularly in chemicals, vehicles, paper, and mineral products.

• The impact varies among EU member states, with economic size, geographical, and cultural proximity playing significant roles – the closer a country is to the UK, the greater its losses.

Despite the EU and Germany experiencing fewer economic losses from Brexit than the UK itself, the consequences are serious. Both sides are suffering from the uncertainty surrounding the future development of economic relations.

Milestone

Bridging the Divide: Germany’s Economic Union

In 1990, Chancellor Helmut Kohl made a bold promise to transform the regions of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony-Anhalt, Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia into thriving landscapes where people would want to live and work. Despite these aspirations, even three decades after the Berlin Wall came down, the economic vitality of former East Germany remained markedly below that of the West. The ifo Institute’s Dresden branch has been tracking this structural transformation since 1993.

Merging Economic Landscapes

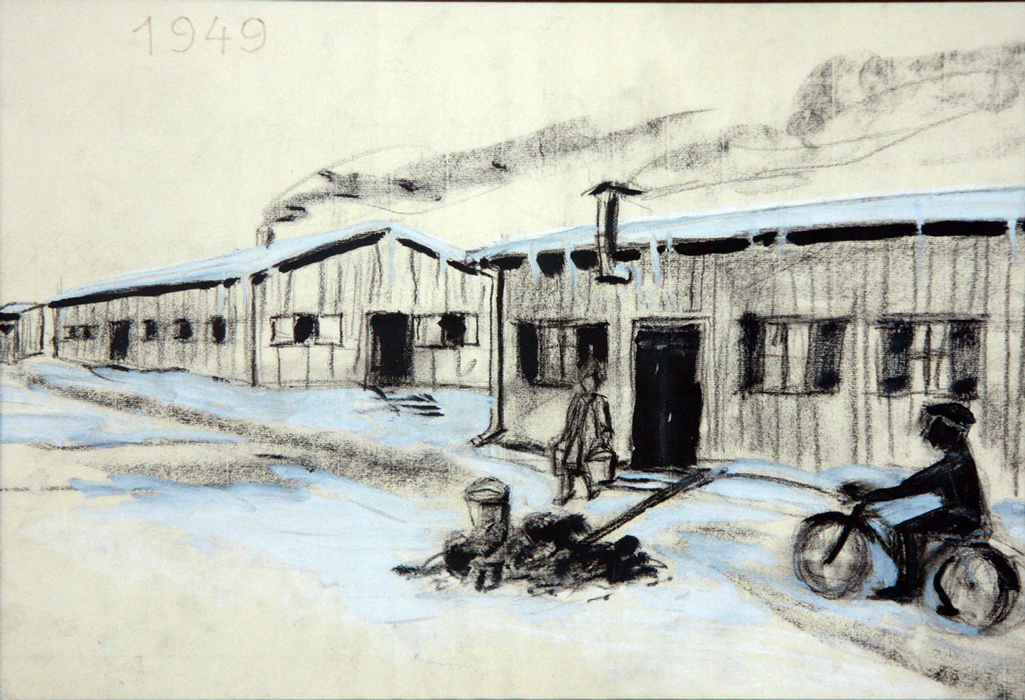

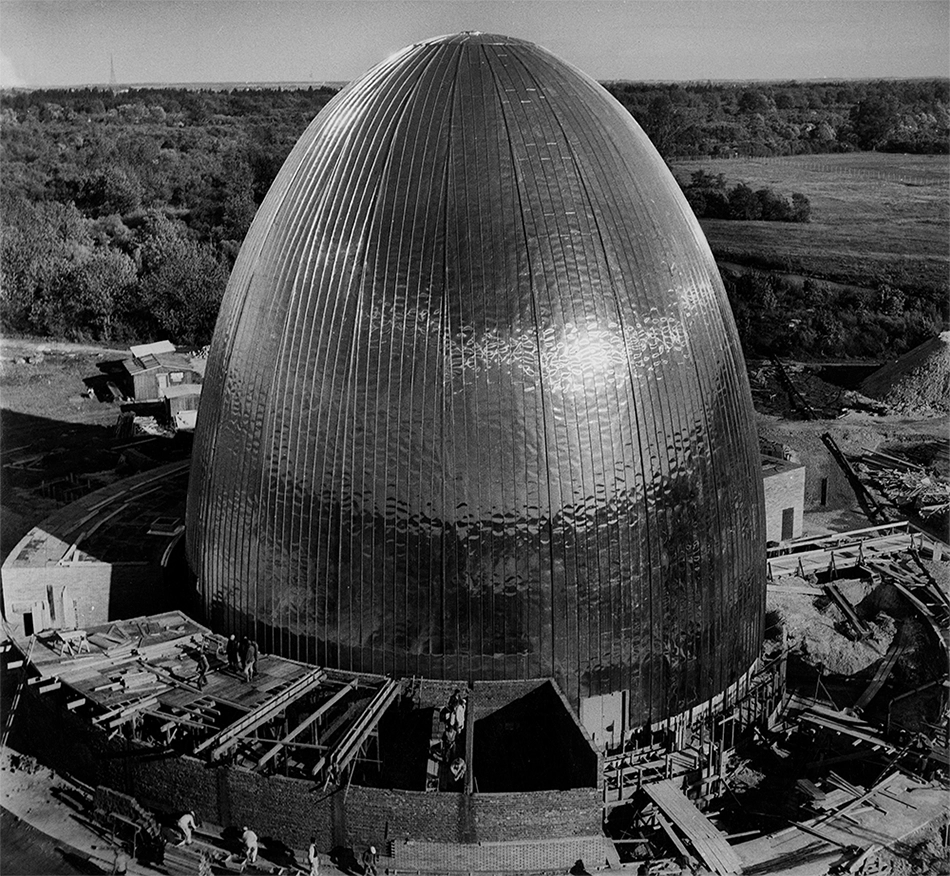

The Berlin Wall’s fall in 1989 paved the way for the State Treaty on Economic, Monetary, and Social Union in July 1990, heralding the economic merger of Germany. The Deutsche Mark became the national currency across both East and West Germany, extending the social market economy’s principles to the newly incorporated federal states. This transition placed immense pressure on East German enterprises to adapt quickly. The Treuhandanstalt, a public agency tasked with privatizing over 12,000 state-owned businesses, failed to find buyers for about 3,000, leading to their closure. To stave off an economic downturn, the federal government launched the “Gemeinschaftswerk Aufschwung Ost” (Joint Initiative for East Germany) in 1991, introducing the solidarity surcharge among other tax increases to fund this support.

Economic Progress Since 1989

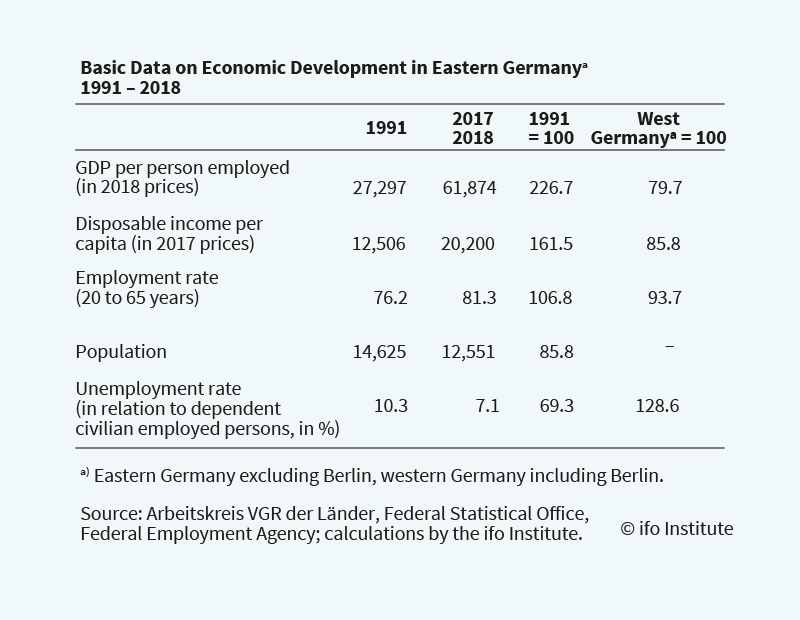

By the late ’80s, East Germany’s economy lagged in competitiveness. The conversion rate between the GDR Mark and the Deutsche Mark was unfavorably high. Overnight, West German laws took effect in the East, further straining its struggling economy. “Looking at East Germany’s economic trajectory from the initial years post-reunification, the strides made are impressive,” notes Joachim Ragnitz, Deputy Director of the ifo Institute’s Dresden branch. Following reunification, East Germany saw a significant population decline due to lower birth rates and mass emigration, reducing the population by over 2 million since 1991 and those of working-age by more than 10 percent.

Yet, by the end of 2023, unemployment had drastically fallen from highs of around 20 percent to just 7.1 percent, after having averaged 7.6 percent in 2018. Economic output, risen by 127 percent, real disposable income, risen by 62 percent, and job numbers per working-age individual had seen substantial increases by 2018.

Comparison with the West

Residents of the eastern states often measured their progress against the West, feeling dissatisfied despite considerable advancements. Economic output and wages in the East only reached about 80 percent of the West’s average, with disposable income just catching up to the levels of Bremen and Saarland.

“Public perception of wage disparities fuels discontent,” Ragnitz explains. In 2018, the median wages for full-time workers in the East were 79 percent of those in the West, partly due to structural differences, such as a higher percentage of workers in low-wage sectors, 38.1 percent in the West and 42.9 percent in the East, and a scarcity of large corporations in the East, affecting overall wage averages.

Addressing Structural Shortfalls

Three decades post-reunification, East Germany had only managed to match West Germany’s economic output from the mid-80s. Persistent structural challenges – like fewer large firms, limited headquarters presence, a shortage of skilled professionals, and reduced research and development activities – continued to impede the East’s growth. “Considering these challenges... it’s notable that the East has managed to keep pace with the West’s economic growth in recent years at all and not falling further back,” Ragnitz points out. He suggests that the general sentiment might be gloomier than the actual circumstances, advising politicians to navigate beyond perceived public moods.

Milestone

Can We Do It? – Flight and Migration in 2015

At the Federal Press Conference on August 31, 2015, Chancellor Angela Merkel left no room for doubt: “We can do it.” Hardly any other sentence is so strongly associated with her term of office. The situation was critical: Shortly beforehand, the Federal Ministry of the Interior had announced that the number of migrants would rise to 800,000 by the end of the year. Merkel tried to brace the country for this huge challenge: “Whenever it matters, we – the federal government, federal states and municipalities – are able to do what is right and necessary. Germany is a strong country. The spirit we need to tackle these things must be: We have managed so much – we can do it!”

Fleeing from Dictatorship and Terror

The war in Syria was the main cause of the large flow of refugees in 2015. Most of the populace simultaneously faced existential threats from two sides, as the terrorist organization Islamic State grew in strength Syria and Iraq in 2014 and the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad sought to maintain his draconian rule. Fleeing from Syria to Turkey and from there to the Greek island of Lesbos seemed to be the last resort for many people who feared for their lives. The Greek authorities refrained from registering the refugees in an orderly manner and channeled the flows to Hungary and Austria through the Western Balkans.

The Background

Between 2003 and 2013, around 34,000 people a year applied for political asylum in Germany. That figure was 173,000 in 2014 but soared to 800,000 in 2015. Most of them came from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. Initially, their escape route took them through the Balkans, in other words, via Greece, North Macedonia, Serbia and Hungary to Austria. By mid-2015, around 150,000 people had reached Hungary and were accommodated in camps there. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán ordered the borders to Serbia to be closed in June. In addition, television pictures flashed around the world showing the harsh treatment meted out by the Hungarian police to refugees. In view of these events, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees decided to allow people from Syria to enter Germany – even if they had not registered in another EU country.

Germany as a Safe Haven

The upshot was that many refugees no longer wanted to register in Hungary at all, but instead tried to travel directly to Germany. Riots broke out in some camps. In Burgenland, a truck was found containing more than 71 refugees who had suffocated after apparently being packed inside by smuggling rings and abandoned. The picture of the young Alan Kurdi also provoked outrage. The child drowned during the onward journey from Turkey to Greece. Angela Merkel’s decision to help those affected as quickly and comprehensively as possible should also be understood in light of the enormous pressure from the media.

Since 1949: The Fundamental Right to Asylum

The right to political asylum in Germany is governed by Article 16 of the Basic Law. In paragraph 1, it states: “Persons persecuted on political grounds shall have the right of asylum.” And paragraph 2 reads: “Paragraph (1) of this Article may not be invoked by a person who enters the federal territory from a member state of the European Communities or from another third state in which application of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms is assured.” That prompted critics of unrestricted admission of refugees to ask who was regarded as politically persecuted and why those coming from safe third countries such as Hungary and Austria should also enjoy a fundamental right to asylum.

The historical background to the right to political asylum being enshrined in the Basic Law was the expulsion of German Jews during the National Socialist regime. These refugees often had great difficulty obtaining political asylum in other countries, such as Switzerland.

What is the Situation 10 Years On?

Around 55 percent of refugees who came to Germany in 2015 are now in employment. Integration into the labor market appears to be working and that percentage is expected to increase significantly in the coming years. The economist Jan Kluge pointed out the importance of integration back in 2015 in a publication by the ifo Institute. The considerable increase in immigration would counteract population decline in Germany, but the positive effects on the business location

could only be achieved through comprehensive integration into the labor market. Immigration and the successes and problems of integration will continue to spark a passionate political debate in the coming years, including in other EU countries. Some observers see the events of 2015 as the basis for the growing success of right-wing populist parties such as the AfD.

Milestone

Celebrating Excellence: CESifo‘s Nobel Laureates

Today, marking 25 years since its inception, the CESifo network stands as one of the largest economic research collectives globally. Regular gatherings in Munich and around the world foster an exchange of ideas among international researchers, enhancing their understanding of complex economic issues. The prestige of this network is underscored by the exceptional caliber of its members, including 13 Nobel laureates from its ranks of over 2,000 members.

Tracing Women in the Labor Market

Among the distinguished is Claudia Goldin, Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University, who became only the third woman ever to receive the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2023. And she won it for her research in a field that, for a long time, also received little attention. Her work explores the historical role of women in the labor market, tracing back to the 18th century to uncover roots of present-day wage disparities, family structures, and educational inequalities. Claudia Goldin has been a member of the CESifo network since 2022 and is one of six CES Fellows to receive this coveted award by the Royal Swedish Academy.

Labor Market Dynamics

David Card, another notable CESifo member since 2024, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2021, together with Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens. His empirical research in labor economics, particularly his findings that increased minimum wages do not necessarily reduce employment, challenges long-standing economic assumptions.

He deals with central and real-life questions – why do people succeed or fail in the labor market? What factors drive wage inequalities? Given his wealth of publications and findings, it is all the more astonishing that David Card originally studied physics and only later switched to economics.

Development Economics and Poverty Reduction

Before Claudia Goldin, Esther Duflo was the second woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences from the Royal Swedish Academy. Awarded in 2019, she shared this honor with her husband, Abhijit Banerjee, and Michael Kremer. Duflo stands out as the youngest economist to receive this distinction. Specializing in development and social economics, her passion for addressing poverty, hunger, and social inequality was influenced by her mother, a pediatrician who worked with humanitarian organizations. It seems almost destined that Duflo would earn the Nobel Prize for her groundbreaking work in poverty research. Since the 1990s, she and her research partners have been using field experiments to devise effective strategies to combat global poverty. Esther Duflo has been a valuable member of the CESifo Network since 2013, contributing her expertise and experience.

Principles of Human Behavior

Many people see contracts as one thing above all else: Sheets of paper and tedious bureaucracy. The Finnish economist Bengt Holmström, however, who joined CESifo in the same year he won the Nobel Prize in 2016, has significantly advanced the understanding of contract theory, particularly in how companies can optimize CEO contracts. His work has broader implications for corporate governance and legal frameworks, offering new perspectives on human behavior and economic incentives within corporate structures. As he comes from the Swedish minority in Finland, he is probably one of the few laureates who could follow the ceremony in his native language.

Practical Insights in Contract Theory

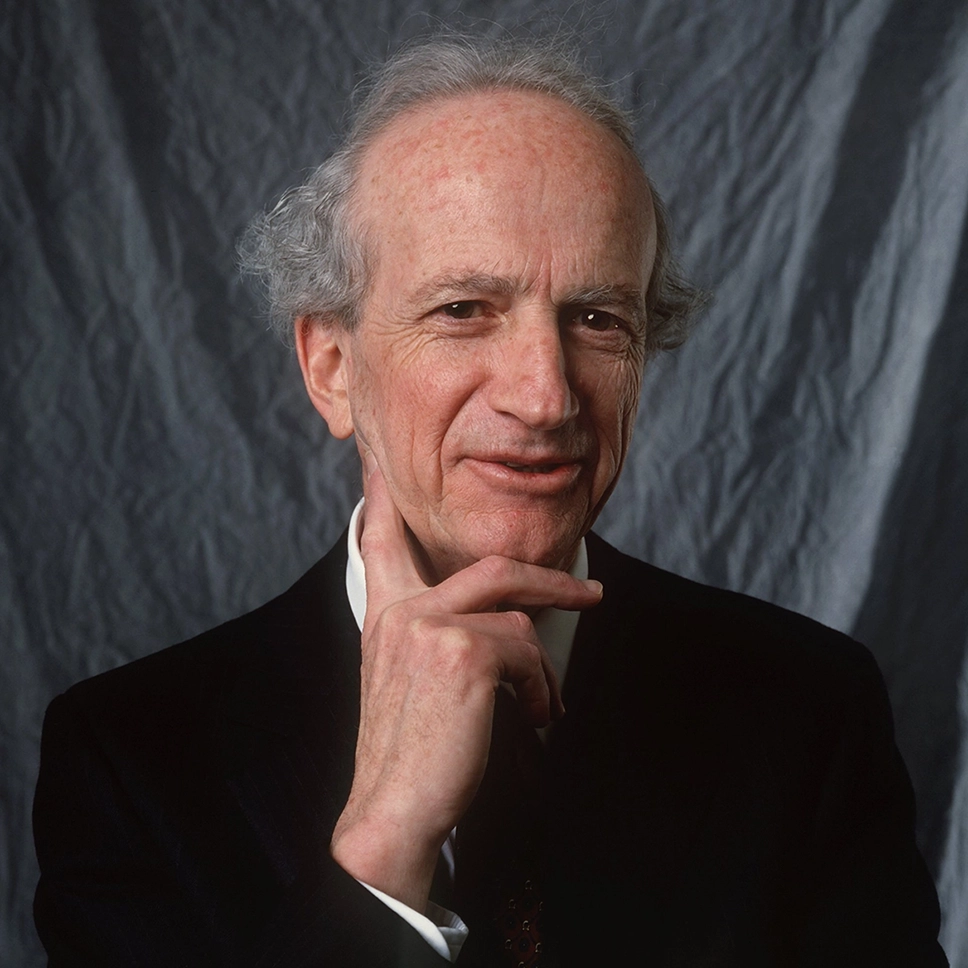

2016 was a good year for Nobel Prize winners in the CESifo network. In addition to Bengt Holmström, the jurors decided to award the prize equally to Oliver Hart from Harvard University and his contribution to contract theory. A foundational figure in contract theory, Hart’s innovative work has profoundly influenced both academic thought and practical policy. Journalists, for example, maintain the conviction that Hart influenced the U.S. government in its decision to no longer leave the management of prisons to private contractors. An active member since CESifo’s inception year 1999, his insights have shaped our understanding of how contracts are utilized within and outside the marketplace. Hart’s contributions were recognized with a Nobel Prize, and his ongoing impact was further acknowledged with a knighthood by King Charles III in 2023.

Leaving Poverty Behind

Scottish economist Angus Deaton delves into whether wealth equates to happiness, applying a rigorous economic perspective. Deaton, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2015 – a year before Hart and Holmström – received this honor for his lifetime contributions, as noted by the committee. His profound insights into need may stem from his own humble beginnings. Deaton’s research focuses on how individual spending patterns influence societal economic development. Throughout his fieldwork, he repeatedly encounters individuals who have remarkably overcome dire poverty, reinforcing his belief that escaping poverty is always possible. Since 2004, he has been sharing these inspiring stories within the CESifo Network, and in 2016, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, becoming Sir Angus Deaton.

The “Application-Oriented Theorist”

A Nobel laureate in 2010, Diamond’s research into markets with search frictions has clarified the dynamics between policies and economic outcomes like unemployment and wages. With him, Dale T. Mortensen and Christopher A. Pissarides also received the prize. An “application-oriented theorist”, as Nobel Prize winner Eric Maskin once called him, Diamond‘s analysis of pension structures contributed to the reform of the U.S. system and the reconstruction of the Polish pension system. Peter A. Diamond, CESifo member since 2000, strives to get to the bottom of things – a fact that is also shown by his subsequent studies at Harvard Law School. Diamond is now Professor Emeritus at MIT, where he taught from 1966 to 2011.

The Human Factor

His own website describes Edmund S. Phelps‘ life‘s work as a project to embed “people as we know them” in economic theory. Phelps received the Nobel Prize in 2006 “for his analysis of intertemporal tradeoffs in macroeconomic policy”. His pioneering research began in the 1960s, challenging the then-prevailing assumptions about correlations between inflation and unemployment. During his career, he worked on various theoretical approaches and always added the human factor. In his analyses, Edmund S. Phelps recognized that the models failed to take into account ill-considered decisions or decisions made in the absence of better information. He has been sharing his approaches as a member of the CESifo network since 2000.

Conflict Theory in the Cold War

As a former classmate of Edmund S. Phelps, it‘s a striking coincidence that Thomas Schelling was awarded the Nobel Prize just a year before him. In 2005, the Royal Swedish Academy recognized Schelling, along with Robert J. Aumann, for advancing our understanding of conflict and cooperation through game theory analysis. During World War II and the early 1950s, Schelling contributed to politics, notably helping to craft the Marshall Plan. His 1960 publication, “The Strategy of Conflict,” remains one of his most renowned works, considered one of the 100 most influential books in the West since 1945. During the Cold War, his studies became particularly influential: Schelling viewed war as a bargaining process and argued that the best defense against a nuclear attack was to safeguard one’s own nuclear arsenal. Thomas Schelling was a valued member of the CESifo Network from its inception in 1999 until his death in 2016 at the age of 95.

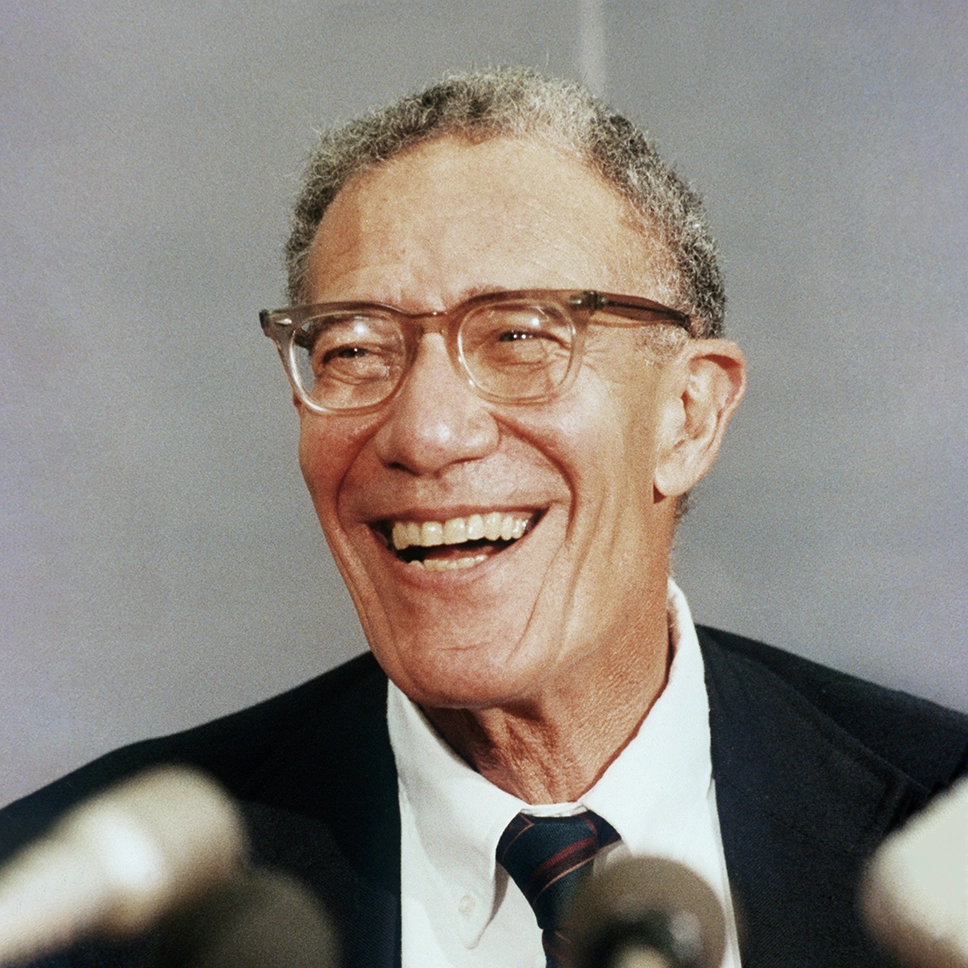

The Heckman Correction

James Heckman's areas of expertise lie in political economy and statistics. He takes a deeply analytical approach to finding where economics and other sciences intersect in order to grasp the essential problems of society. Together with Daniel McFadden, he succeeded in developing “Theories and Methods for the Analysis of Selective Sampling”, which earned them both the Nobel Prize in 2000. His “Heckman correction” technique has enabled economists and policymakers to make more accurate interpretations of data where sample selection is biased. A member of CESifo since 2003, Heckman’s work has bridged the gap between theoretical economics and practical application in fields such as education and labor economics.

Gary Becker

Robert M. Solow

Reinhard Selten

From sociology in economics to game theory

Recognized with the Nobel Prize in 1992, Gary Becker (1930-2014) was a pioneer in extending economic analysis to domains traditionally considered outside economics, such as sociology. A CESifo member since 1999, his approach has influenced broad areas of human behavior and interaction. Awarded the Nobel Prize in 1987, Robert M. Solow‘s (1924-2023) models of economic growth have been fundamental in the study of how economies evolve over the long term. His work emphasizes the role of technological progress and its impact on growth. As a member of CESifo since 1999, the success of Solow’s work also shows in the fact that four of his students, including Peter A. Diamond, were also able to claim the Nobel Prize. As the only German Nobel laureate in Economics, awarded in 1994, Reinhard Selten (1930-2016) was renowned for his refinements of game theory. His work has provided deep insights into economic behavior and strategy, which have had profound implications across various fields. A member of CESifo from 1999 until his death in 2016, Selten’s contributions continue to resonate within the network.

Network

People

Celebrating Milestones: 25 Years of CESifo and 75 years of the ifo Institute

Marking a century of combined knowledge, the ifo Institute and CESifo are celebrating 75 and 25 years respectively – 100 years of scientific rigor influencing and shaping policy across generations. This year, under the banner “75 years of ifo - lots of exciting stories,” we invite you to explore the rich history of economic research and policy advice. Throughout the anniversary year, we will spotlight key events, delve into the institute’s past, present, and future, and introduce the personalities, places, and pivotal moments that have defined our journey.

A Beacon of Economic Thought in Europe

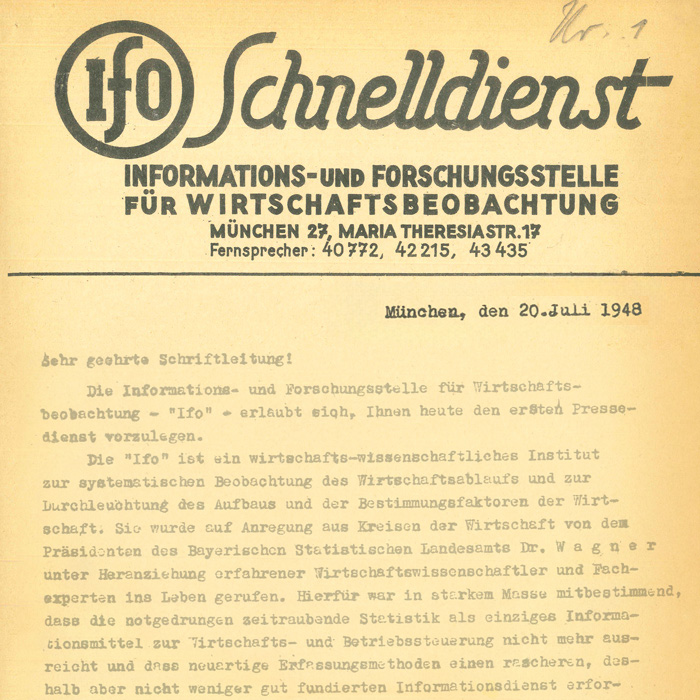

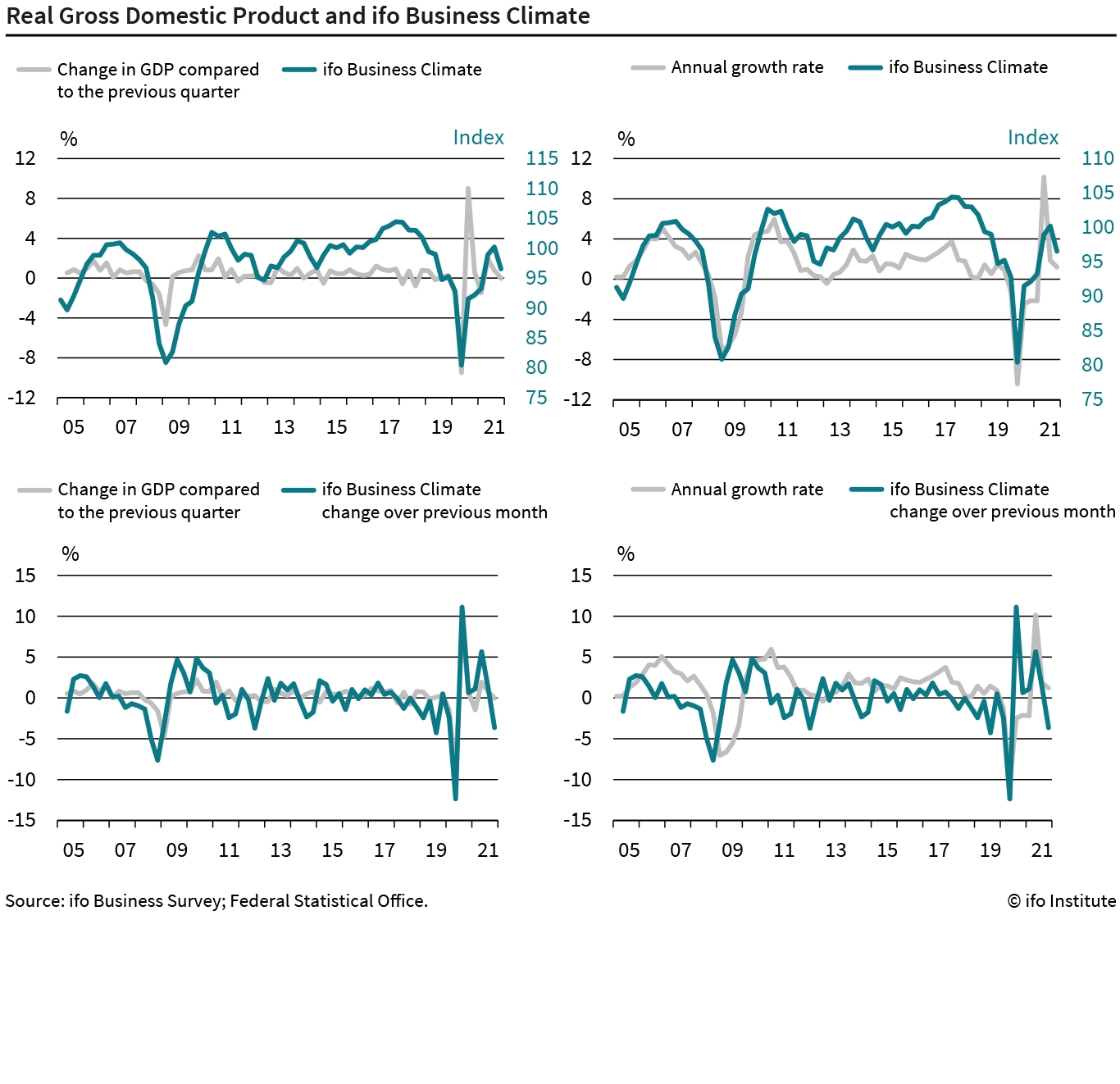

Founded in the aftermath of World War II, the ifo Institute arose from the union of the Information and Research Center for Economic Observation and the South German Institute for Economic Research, established by Ludwig Erhard in 1946. Today, it is renowned for its top-tier economic research and policy advice, boasting an international reputation. “Our research provides the foundation for reliable analyses and data, empowering politicians, businesses, and the public to make informed decisions,” says ifo President Clemens Fuest at the start of the anniversary year 2024. “Our history began with economic monitoring via our own surveys. Today, for example, we are tapping into new data sources – big data – to be able to analyze and interpret economic developments more quickly.”

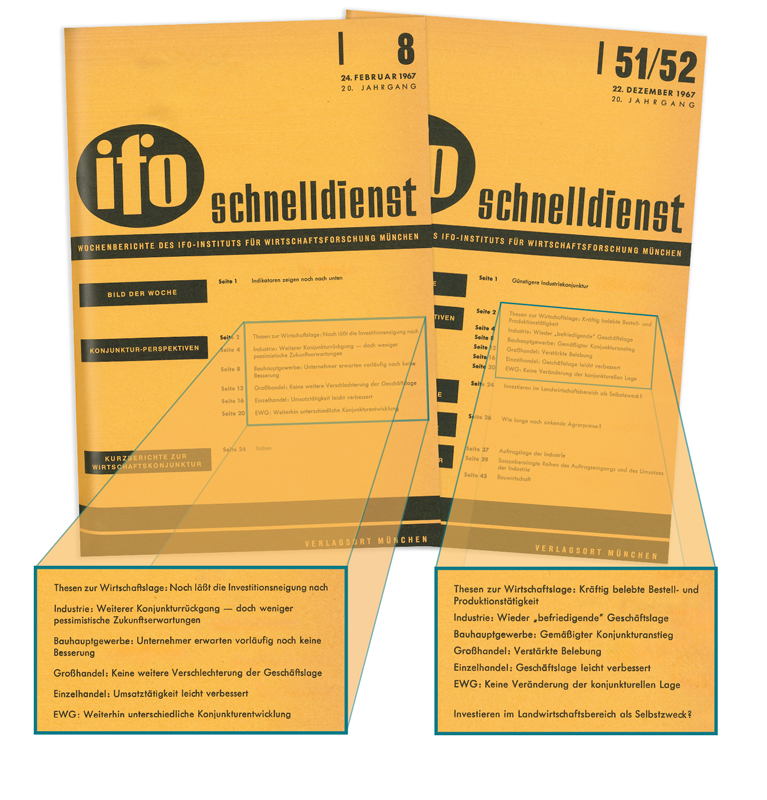

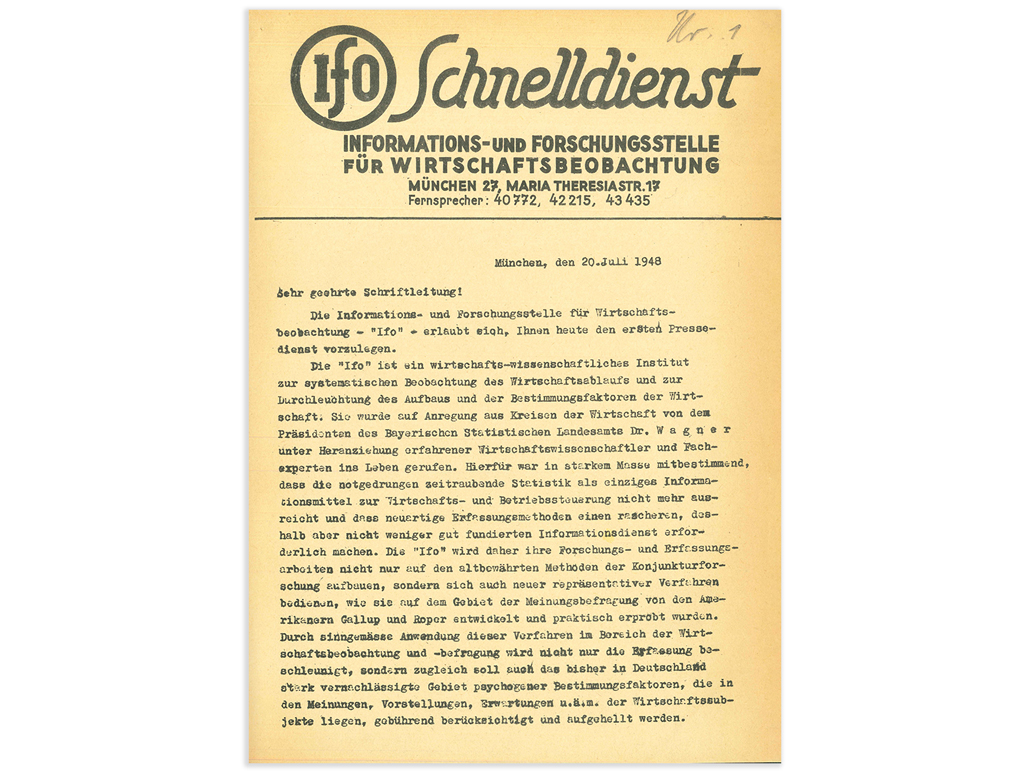

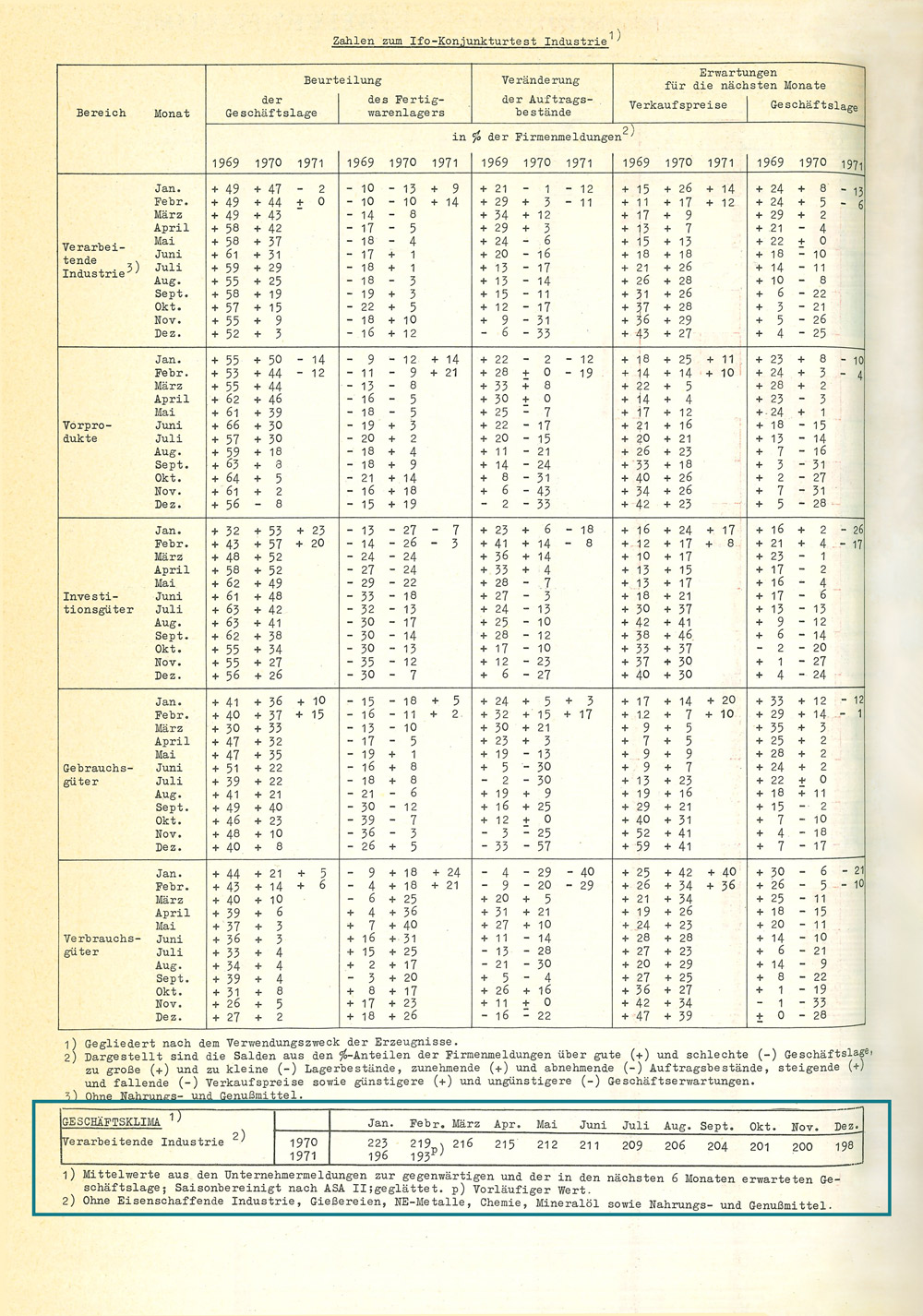

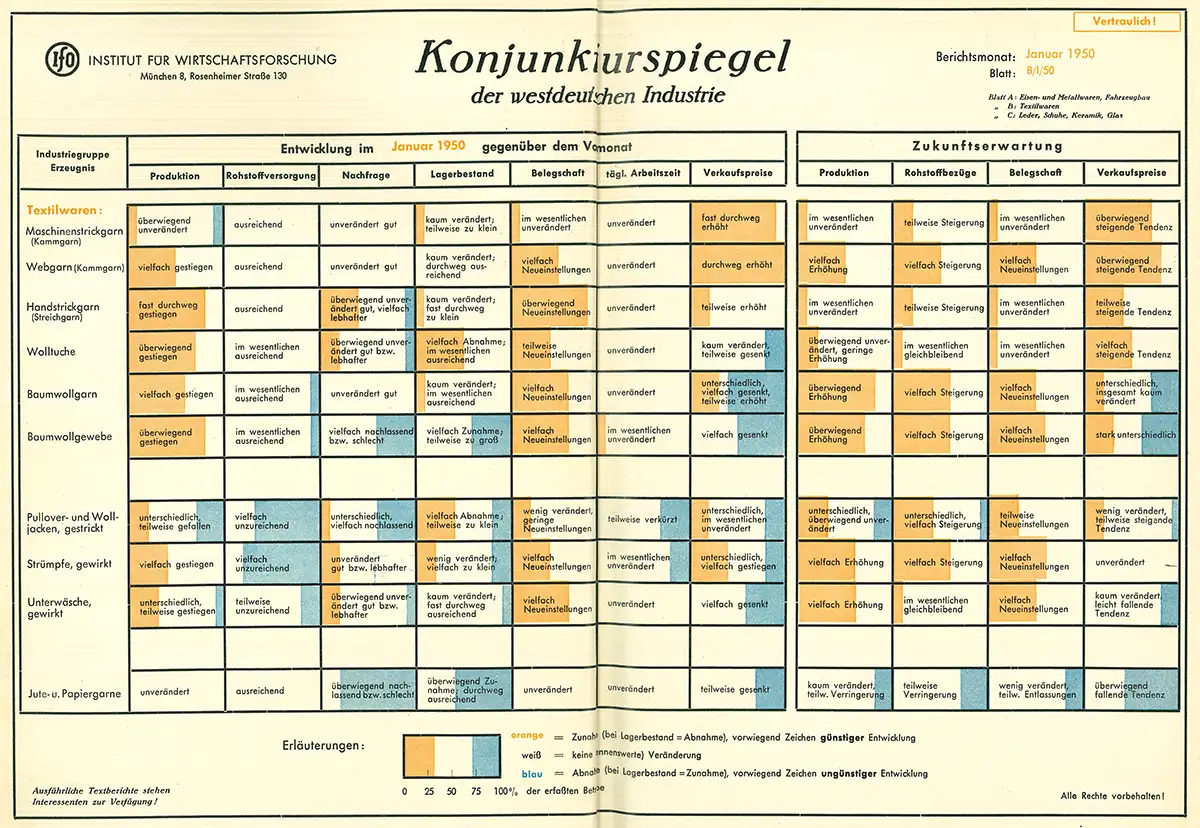

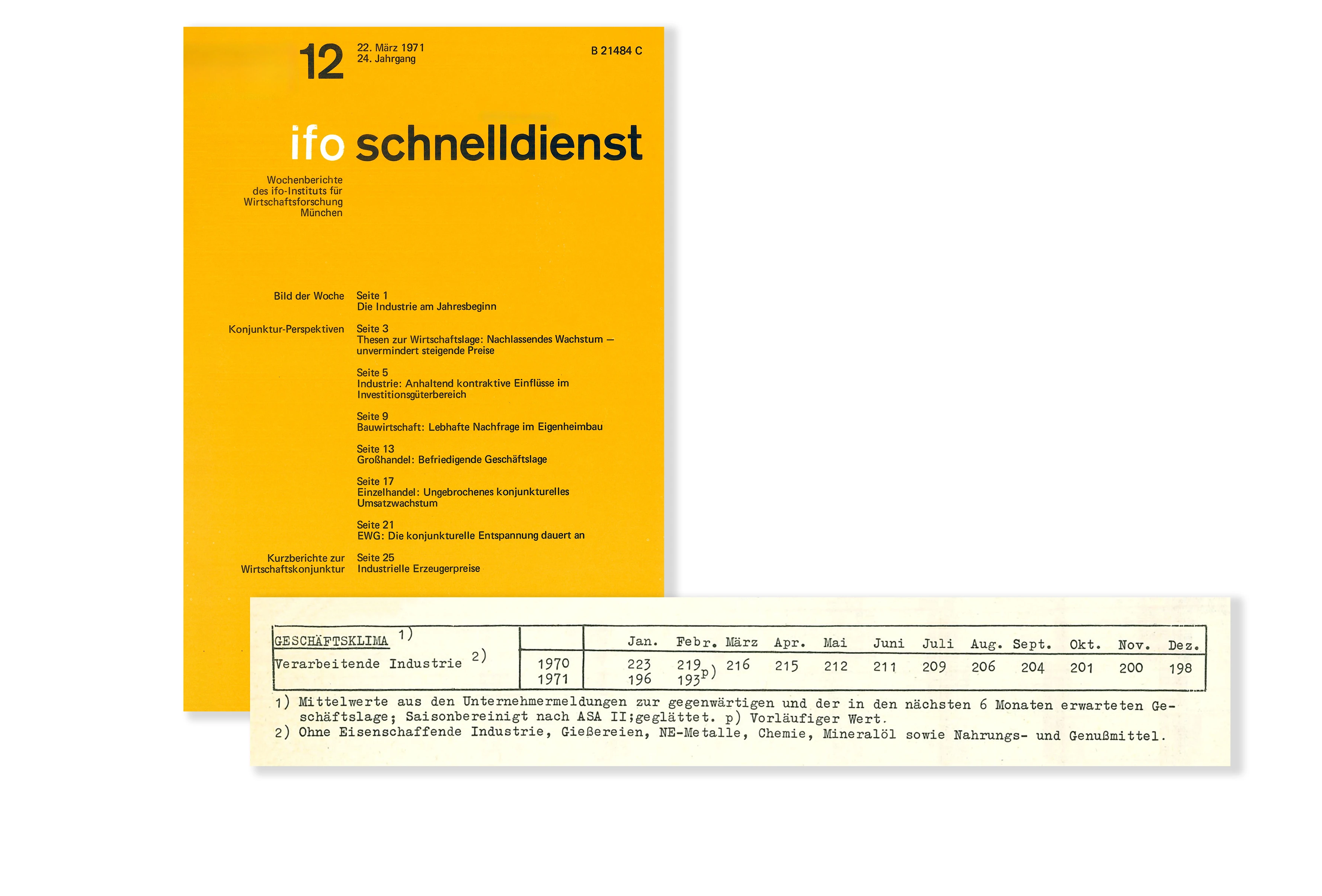

Legacy of the Founding Fathers Erhard, Schlesinger, Pohl

The institute’s operations began on March 1, 1949, with six full-time and twenty part-time employees, including future Bundesbank presidents Helmut Schlesinger and Karl-Otto Pöhl. The current name “ifo,” which stands for “Information und Forschung” (information and research), was added to the institute’s name only in 1950. By the autumn of 1949, the institute had launched its company surveys as an innovative method of economic and business cycle observation. These surveys would become the most important service and hallmark of the institute over the years: even today, they form the basis for the monthly published ifo Business Climate Index, a globally recognized indicator of Germany's economic development.

Expansion and Innovation

Since the German reunification, the ifo Dresden branch, established in 1993, has focused on the structural policy issues of the new federal states, particularly Saxony. In 1999, then-president Hans-Werner Sinn founded CESifo GmbH, creating a global network of over 2,000 economists, including several Nobel laureates. Affiliated with Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München since 2002, the institute recently opened the Ludwig Erhard ifo Center for Social Market Economy and Institutional Economics in Fürth in 2022. In 2023, the ifo Institute revamped the LMU-ifo Economics Business Data Center (EBDC), enhancing its focus on Big Data Economics, which serves as a central research hub for all ifo Centers, their research partners and guest researchers.

“Shaping the Economic Debate”

In addition to economic trends, the institute’s nine research divisions now explore contemporary issues such as climate change, geoeconomics, new technologies, and inequality. The insights gained resonate widely. They are not only discussed within the academic community and published in leading scientific journals, but we also make a concerted effort to cultivate our emerging scholars to ensure research remains at a high level. Moreover, we distill these insights for public discourse. Through media reports and other channels, the ifo Institute’s analyses provide vital information to engaged citizens, business leaders, and association representatives. Additionally, policymakers frequently consult the institute when making significant decisions, underscoring the practical impact of our research.

Beginnings

Impulse

CESifo: 25 Years of Growth

What underpins truly excellent research? Certainly, it involves engaging in meaningful exchanges with peers and effectively disseminating impactful findings. Such were the thoughts 25 years ago that, fueled by a vision from former ifo president Hans-Werner Sinn, gave rise to one of the largest research networks in economics. Today, as CESifo marks its silver jubilee, it continues to thrive and expand.

The Origins of CESifo

Every significant achievement begins modestly. A quarter-century ago, Munich wasn’t yet recognized as a hub for economic research. However, the Center for Economic Studies (CES) at LMU Munich attracted attention; its working papers grew in influence, drawing diverse groups of visiting economists. Inspired by this burgeoning interest, former ifo President Hans-Werner Sinn envisioned a network that would harness this momentum. The participation of 230 guest researchers, the burgeoning publication efforts, and the organization of pivotal research conferences became the cornerstones of what CESifo would represent. These foundational elements are still evident in CESifo’s operations today.

CESifo Today: A Synopsis of Growth and Influence

With over 2,040 economists from 46 countries, more than 11,000 working papers published, and upwards of 800 events attracting over 40,000 participants, CESifo has evolved into a premier, independent global research network in just over two decades. The network brings together distinguished economists across various specialties, each contributing years of experience and expertise. Its mission extends beyond fostering global knowledge exchange on economic topics; it aims to fortify the collaboration between the ifo Institute and LMU Munich and to sustain Munich’s role as a dynamic hub of economic dialogue in Europe.

Interested in learning more about CESifo and the team driving its success? Click below to watch our anniversary video, which offers a glimpse into the network’s events and highlights and introduces the people who are integral to CESifo’s operations. For further details, visit us online.

Network

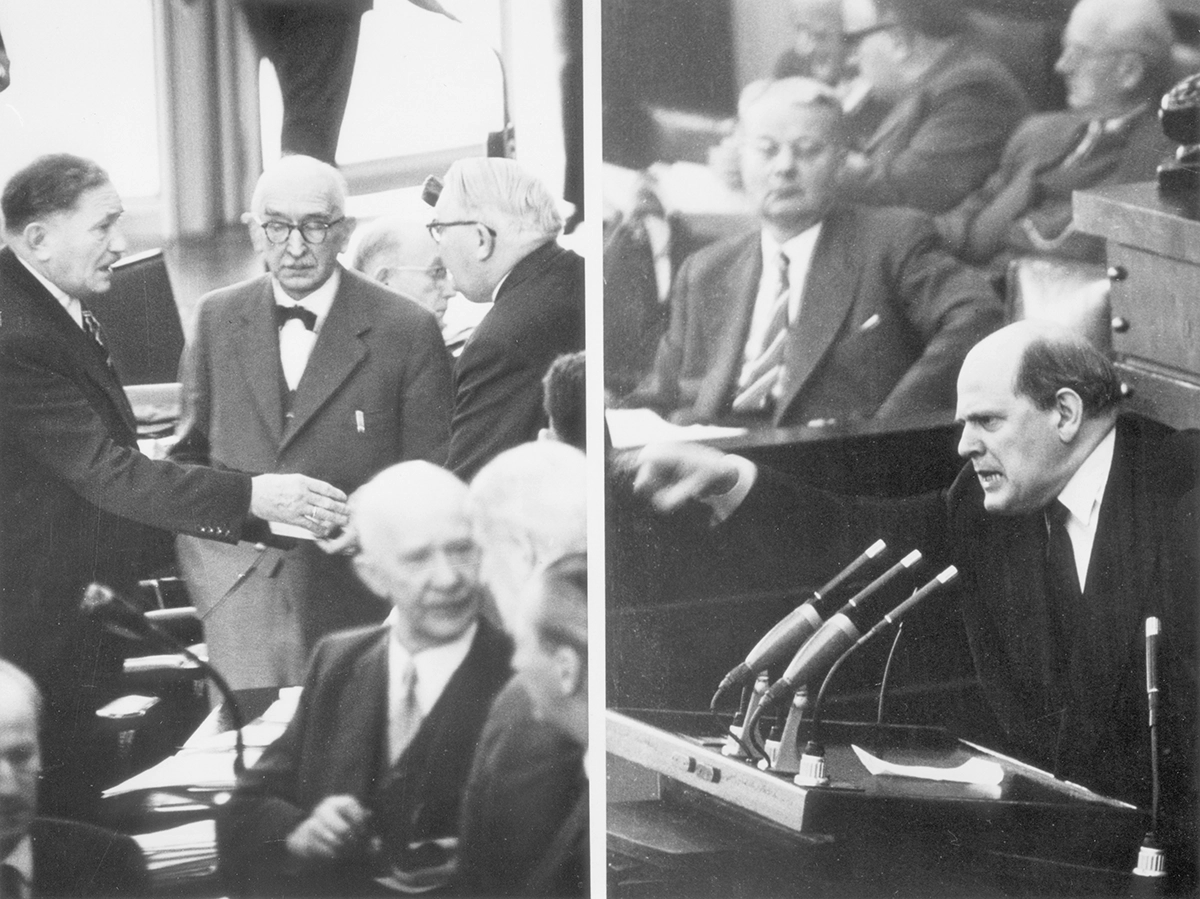

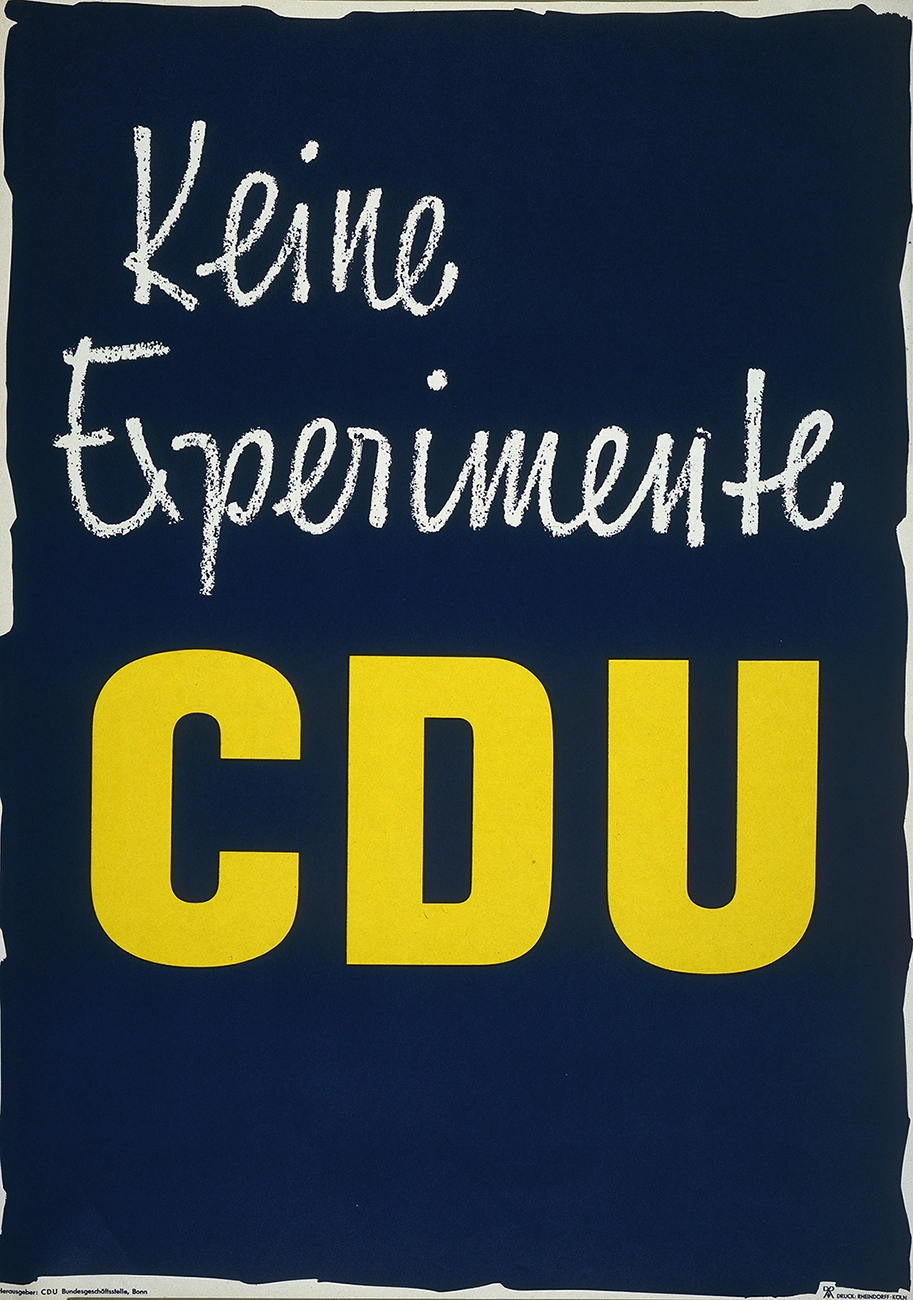

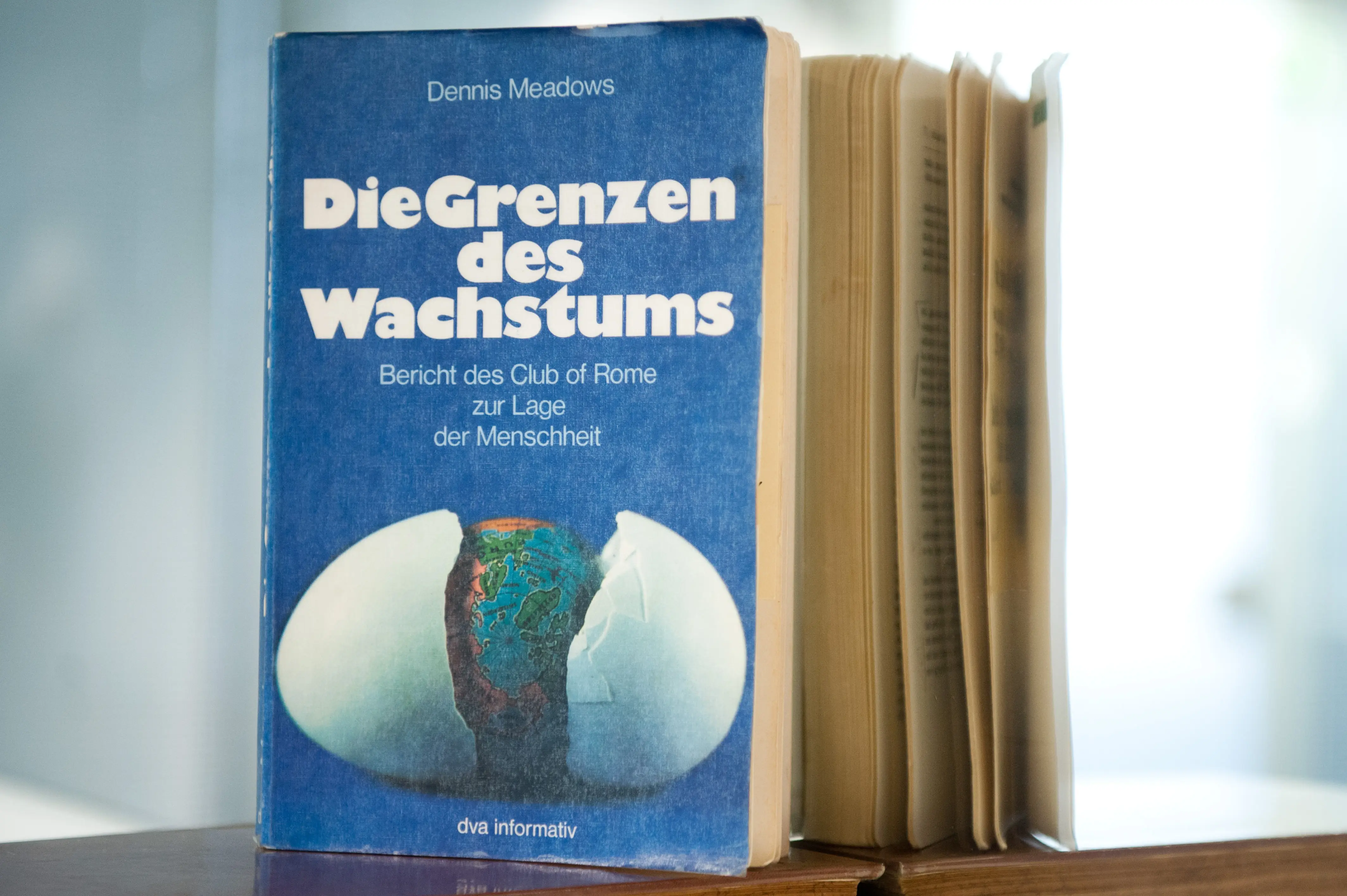

Combating Poverty in Old Age: The 1957 Pension Reform

In the wake of the 1950s’ economic boom, a significant portion of the population, notably the 4.5 million pensioners, found themselves overlooked. In 1957, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer recognized an opportunity to engage a generation that had been previously overlooked, using comprehensive pension reform as a key strategy ahead of the upcoming Bundestag elections. Critics of the reform warned that the central feature – a solidarity-based intergenerational contract – would lead to significant financial challenges for future politicians, especially if birth rates declined, effectively creating a form of hidden national debt. However, Adenauer famously brushed aside these concerns, asserting that “People always have children.” The ifo Institute has actively participated in these discussions, tracing from the initial pension debate in 1956 through to contemporary analyses.

Urgent Calls for Reform

The Invalidity and Old Age Insurance Act, a piece of Bismarck’s social legislation introduced in 1889, provided basic security in old age or in case of occupational disability. However, to meet the full cost of living, individuals often had to dip into their savings or depend on family support. Despite the changing economic landscape, this pension system’s core principles remained unchanged through the post-war period, not accounting for rising prices and wages. Many lost not only their loved ones and savings during the war but also found pensions as their sole income source. The need for reform was clear, yet after initial promises in 1953, Konrad Adenauer’s government faced criticism for its slow action.

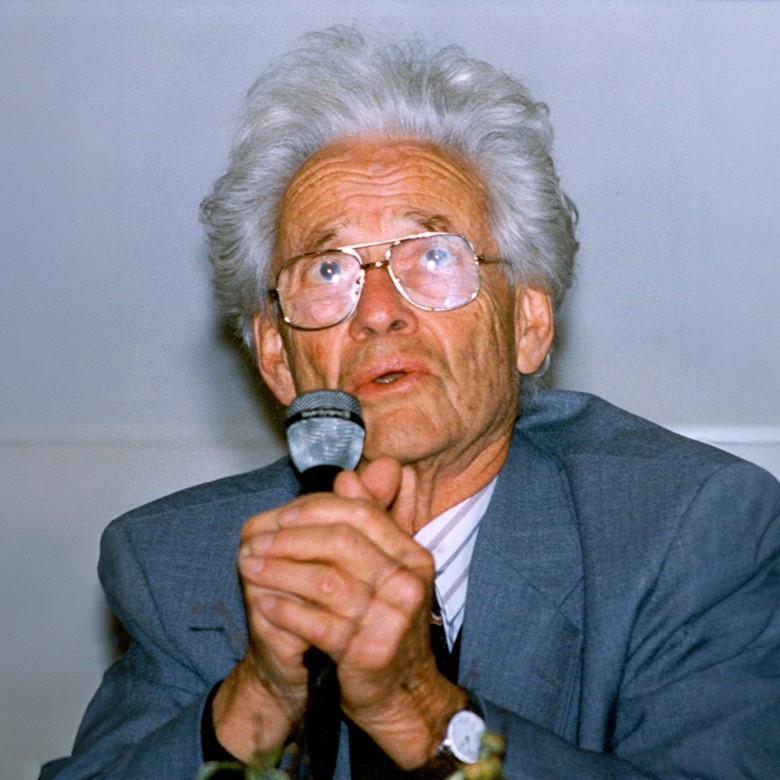

The “Schreiber Plan”

A study by the Federal Statistical Office, commissioned by the Federal Ministry of the Interior on the social conditions of pensioners and benefit recipients, catalyzed the push for significant reform. With the average net pension at 62.90 Deutsche Mark – merely a third of an average wage and below the subsistence level – an increase in social benefits was deemed urgent.

Wilfrid Schreiber, a pre-war writer and journalist, proposed a reform plan. Despite his controversial past, including membership in the NSDAP and involvement in wartime propaganda, the Association of Catholic Entrepreneurs (BKU) hired him as a consultant, and he also taught courses in economic theory, social policy, and statistics at the University of Bonn.

The Reform Draft

Schreiber’s reform proposal envisioned a unified mandatory statutory insurance to replace the separate schemes for disability, employee, and miner’s pensions. Crucially, it proposed replacing the existing funded system with a novel pay-as-you-go method. This so-called generational contract required each working individual to pay a certain percentage of their gross income into the pension fund, from which current pension payments would be made. Additionally, Schreiber suggested redefining how pensions were calculated. He developed a formula that was linked, among other things, to general wage developments. This principle of dynamic pensions was intended to bring about a significant increase in social benefits.

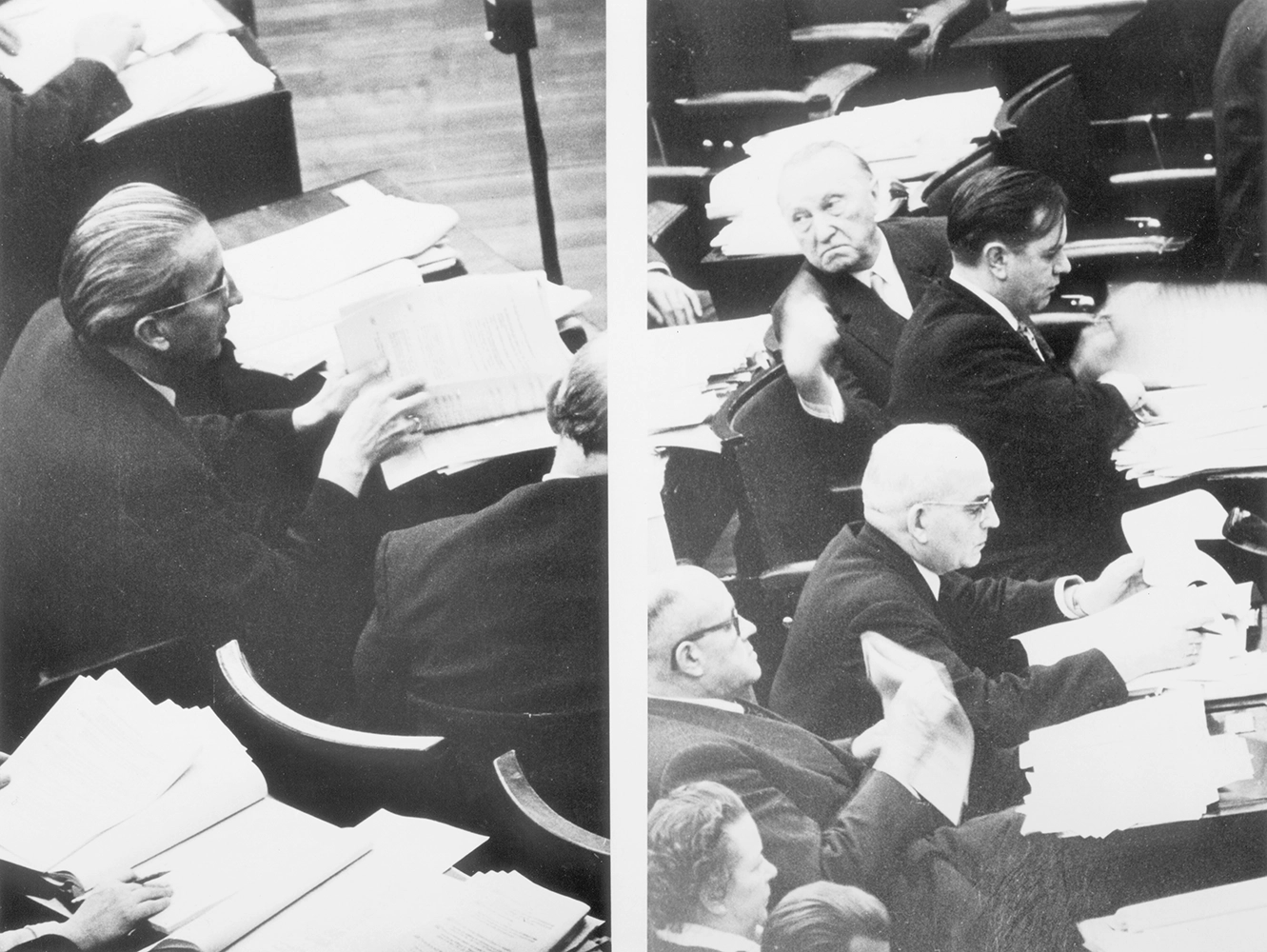

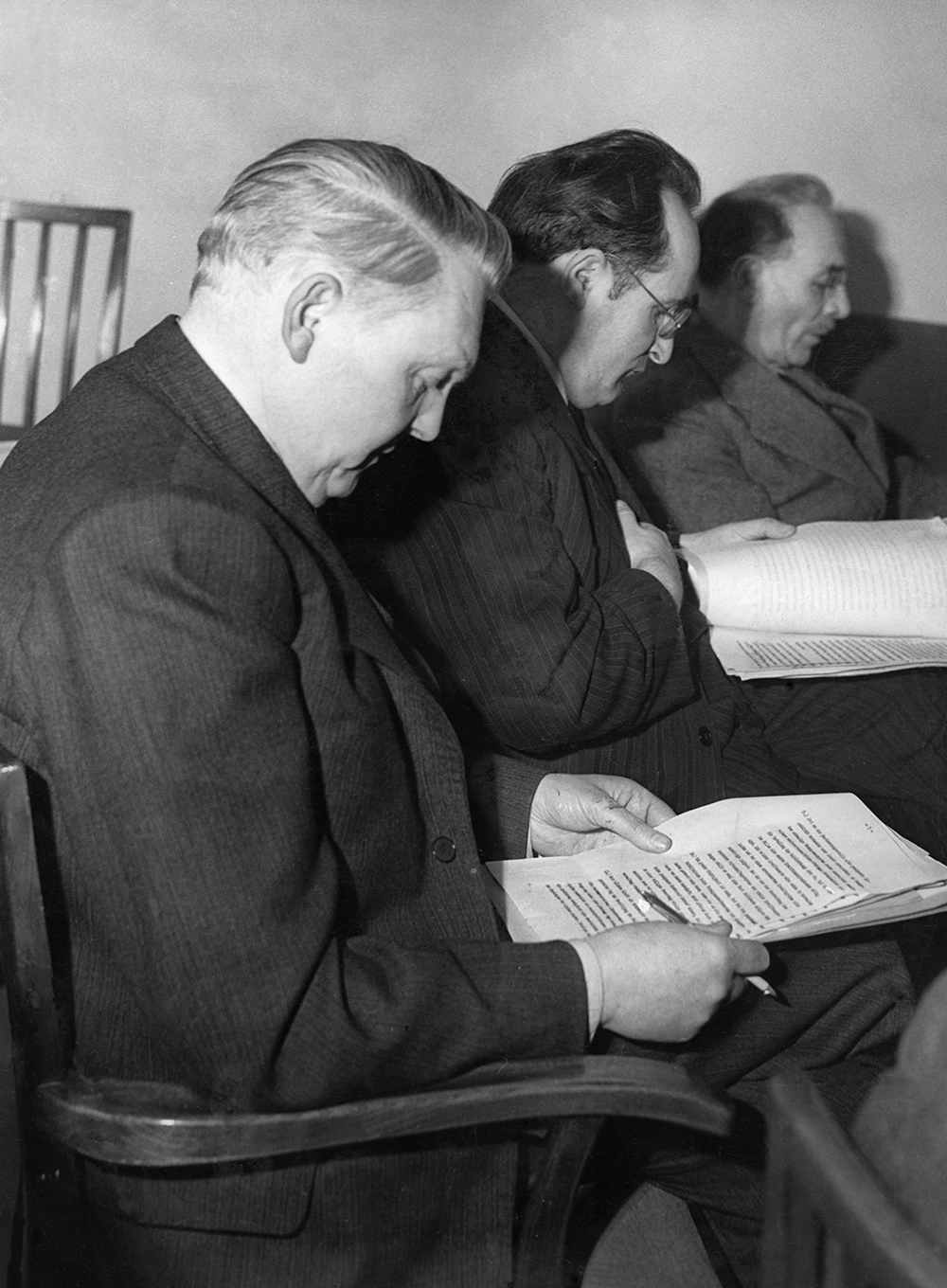

Intense Discussions and Historic Approval

The journey towards the enactment of the 1957 pension reform was marked by profound and, at times, heated debates, earning its place in history as the “pension battle.” In the Bundestag, Germany’s federal parliament, the debates reached their zenith. Members of the Social Policy Committee had already laid the groundwork with spirited discussions, but it was during the bill’s second reading that parliamentarians truly delved into the heart of the matter. For four days, a marathon of speeches unfolded, with parliament dissecting and debating hundreds of paragraphs and amendments. In the end, the Bundestag cast its votes on January 21, 1957, and the reform was approved by a substantial majority.

Konrad Adenauer, the Chancellor, had been a driving force behind the reform, strategically aligning its passage with an eye towards the upcoming Bundestag elections. The first payments under the new system were made in April 1957, setting the stage for a significant electoral victory for the CDU/CSU in the September 1957 Bundestag elections, where they achieved an absolute majority.

Ifo’s contribution to the pension debate

In the lead-up to the pivotal pension reform of 1957, the ifo Institute made significant contributions to the shaping of the debate. In 1956, it published a comprehensive study titled “On the economic problems of dynamic social pensions”.

The study brought to light several fundamental economic concerns associated with the forthcoming reform, which was anticipated to dramatically reshape the West German economy. It argued for minimal state intervention in the pension scheme, proposing that pension adjustments should occur automatically in line with wage and market trends. Moreover, the ifo Institute’s report emphasized the importance of individual responsibility and the need for clear incentives for personal pension planning.

By the time the reform took full effect, the level of benefits had increased by an average of 65 percent. Wages and pensions rose substantially in the years following the reform, with pensions increasing by 110.5 percent by 1969, nearly keeping pace with a 115.7 percent rise in wage levels. This alignment ensured that pensions were sufficient to cover living expenses, a marked improvement from the pre-reform era. The switch to the pay-as-you-go system also enhanced the reliability of the pension system, safeguarding it against the economic volatility that had previously eroded its value.

Milestone

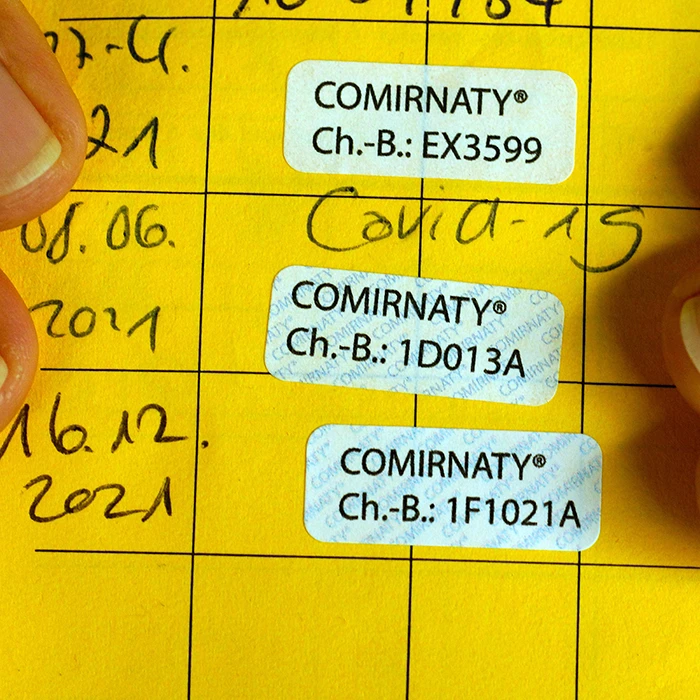

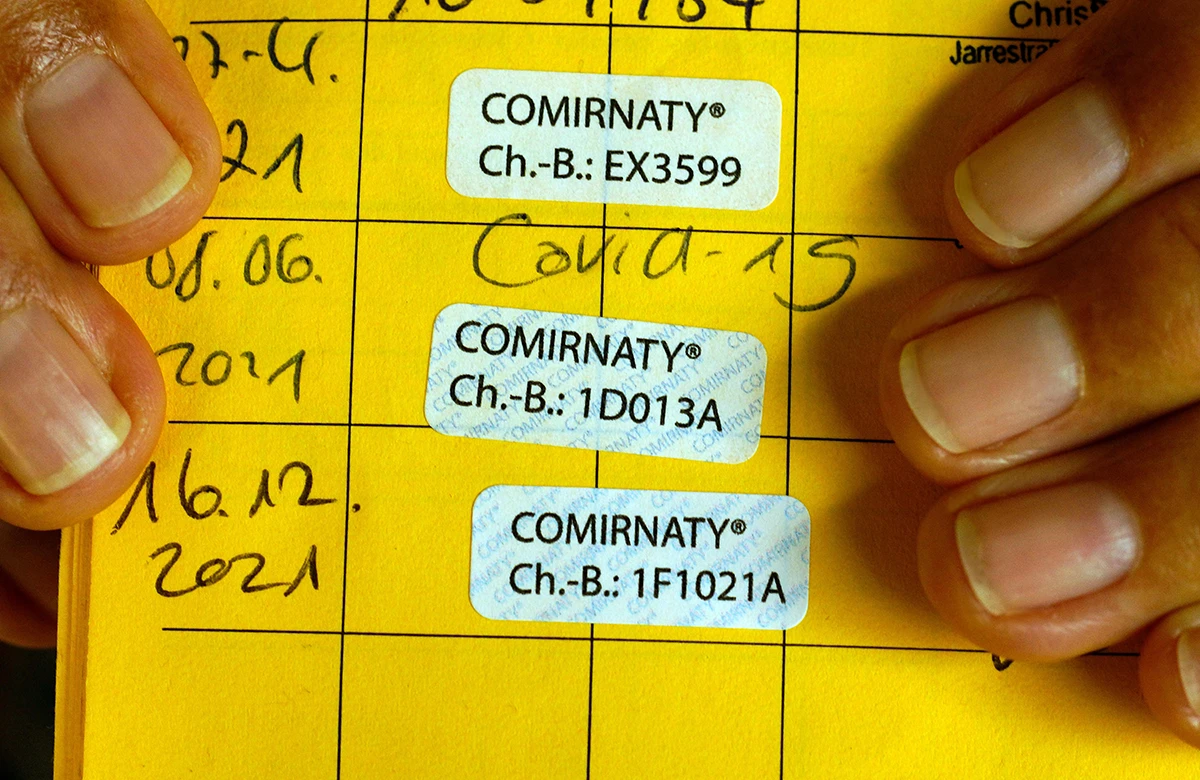

COVID: A Virus Changes the World

December 31, 2019: Authorities in the Chinese mega-city Wuhan informed the World Health Organization (WHO) about an outbreak of a previously unknown lung disease. A novel coronavirus variant was identified as the cause on January 7, 2020. On January 30, the WHO declared a public health emergency of international concern. The coronavirus pandemic spread rapidly, changing the world as we knew it. Right at the beginning of the pandemic, the ifo Institute showed that containing the number of infections and curbing the economic consequences went hand in hand – and were not conflicting goals, as many claimed.

Global Economic Impact

The global economic repercussions of the coronavirus outbreak were discussed at the G20 summit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on February 22, 2020. There was still hope of containing the virus’ spread and that there would only be a short-lived economic slump. Yet it was already too late. The international financial markets tumbled dramatically in February. The world stood on the brink of a severe economic crisis. For the first time in its history, the ifo Institute published an interim Business Climate Index on March 19, revealing the sharpest decline in business expectations in its 70-year history. Other indicators also plunged. In the assessment of ifo President Clemens Fuest, a global economic crisis with more dramatic consequences than the 2009 financial crisis loomed.

“It’s Serious. Take it Seriously Too!”

Angela Merkel addressed the German people with those dramatic words in a televised speech on March 18, 2020. And the calculations by the ifo Institute in February 2022 showed just how serious the pandemic’s consequences were not only for people’s lives and health, but also for prosperity. COVID caused EUR 330 billion in economic losses for Germany in 2020 and 2021, corresponding to a drop of ten percent compared to overall economic output in 2019. Before the pandemic, economic growth of 1.3 percent in each of those years had been forecast.

Exceptional Measures

A total of 13 researchers from various disciplines – including the virologist Melanie Brinkmann, the sociologist Heinz Bude, the internist Michael Hallek, the political scientists Maximilian Mayer and Elvira Rosert, the physicists Michael Meyer-Hermann and Matthias Schneider, and the economists Clemens Fuest and Andreas Peichl – published a joint paper on combating the pandemic in January 2021. Their main goal was to significantly reduce infections while maintaining industrial production and enabling local openings through extensive testing. The plans likewise included a testing, contact tracing and isolation strategy as well as local outbreak management. Phases necessitating rigorous measures would repeatedly be superseded by one where an easing of them was allowed. The strategy was envisaged as an infection prevention concept for the whole European Union.

Economy under Pressure

German industry in particular suffered heavy losses during the first coronavirus wave in spring 2020. That was due to the lockdowns and company closures, but also to impediments to international trade and the growing recession in countries that were important trading partners. For instance, German goods exports dropped by almost 33 percent in March and April 2020, while industrial production fell by around 25 percent.

Sectors of the economy that relied on personal contact with customers experienced a rapid slump. The ones mainly hit were brick-and-mortar retail, hospitality, arts and entertainment, and service businesses such as hairdressing salons and beauty studios. In 2020, around 3.3 million people were employed in brick-and-mortar retail, 2.4 million in hospitality, 1.3 million in arts and culture, and 0.3 million in the social service sector.

Government Aid in Germany

In view of these dramatic developments, the German government adopted comprehensive aid packages. For example, the income lost by the unprecedented figure of 10.2 million short-time workers reported by the end of April 2020 was cushioned by compensation payments. The support measures for companies were able to prevent the anticipated wave of insolvencies. In contrast to the temporary and targeted aid measures, the EUR 130 billion economic stimulus package, which Finance Minister Olaf Scholz termed “Ka-Boom” when it was passed on June 3, aimed to boost future economic growth and innovations so as to ensure competitiveness.

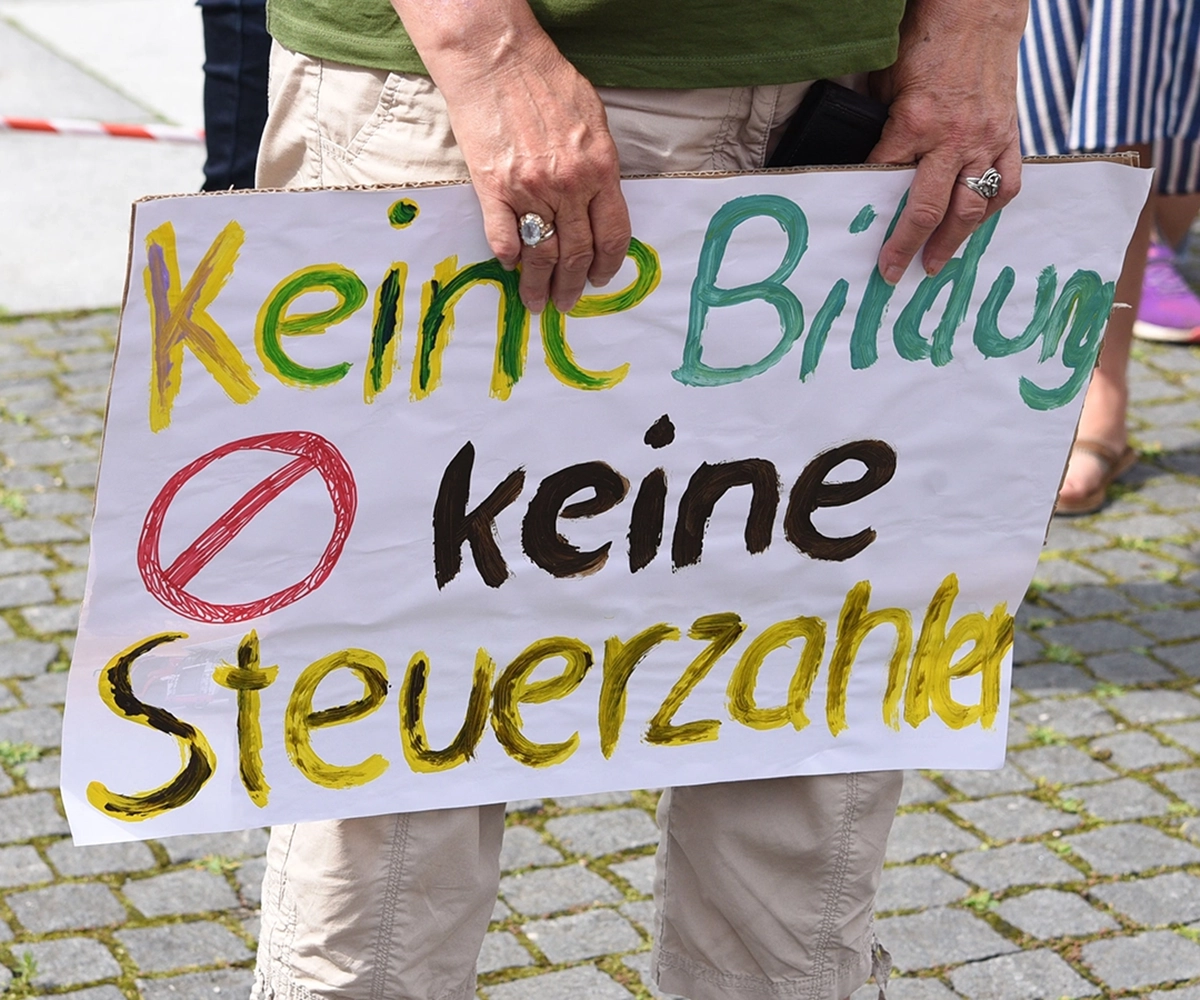

Pupils without School

The coronavirus crisis posed particular challenges for the education system. Surveys by the ifo Institute came to the conclusion that school closures had halved the time in which pupils were able to engage with subject matter in lessons together. Remote learning was not able to plug that gap. Moreover, the lockdown meant children spent far more time on their smartphones and computers. If they were from educationally disadvantaged families, they were particularly handicapped because they had no one at home to help them learn. Germany also had a lot of catching up to do when it came to developing digital teaching methods. In the assessment of the ifo Center for the Economics of Education, the skills not acquired during the coronavirus pandemic may have repercussions and effects on future careers and reduce lifetime earnings by around 3 percent – with the foreseeable negative impact that would have on the entire German economy.

After the Crisis...

In April 2023, Minister of Health Karl Lauterbach announced the end of the coronavirus prevention measures, but the long-term consequences of the pandemic remain serious. According to WHO estimates, six to ten million people fell victim to it, while 65 million suffered or are still suffering from long COVID. The trend toward working from home has presented many companies with the challenge of pressing ahead even more resolutely with digitalizing their work processes. Everyday office life and interaction as part of work have to be redefined. Vacant office buildings and the upswing in e-commerce are changing the demands on urban infrastructure.

In many areas, however, the crisis was also seen as an opportunity to instigate important structural changes that would unleash new growth potential. Development prospects in all areas, from ecological restructuring of the economy to expansion of the European single market, meant researchers were hopeful that there would be a rapid economic recovery and a consolidation of public finances. However, these hopes were dashed when Russian troops invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

Milestone

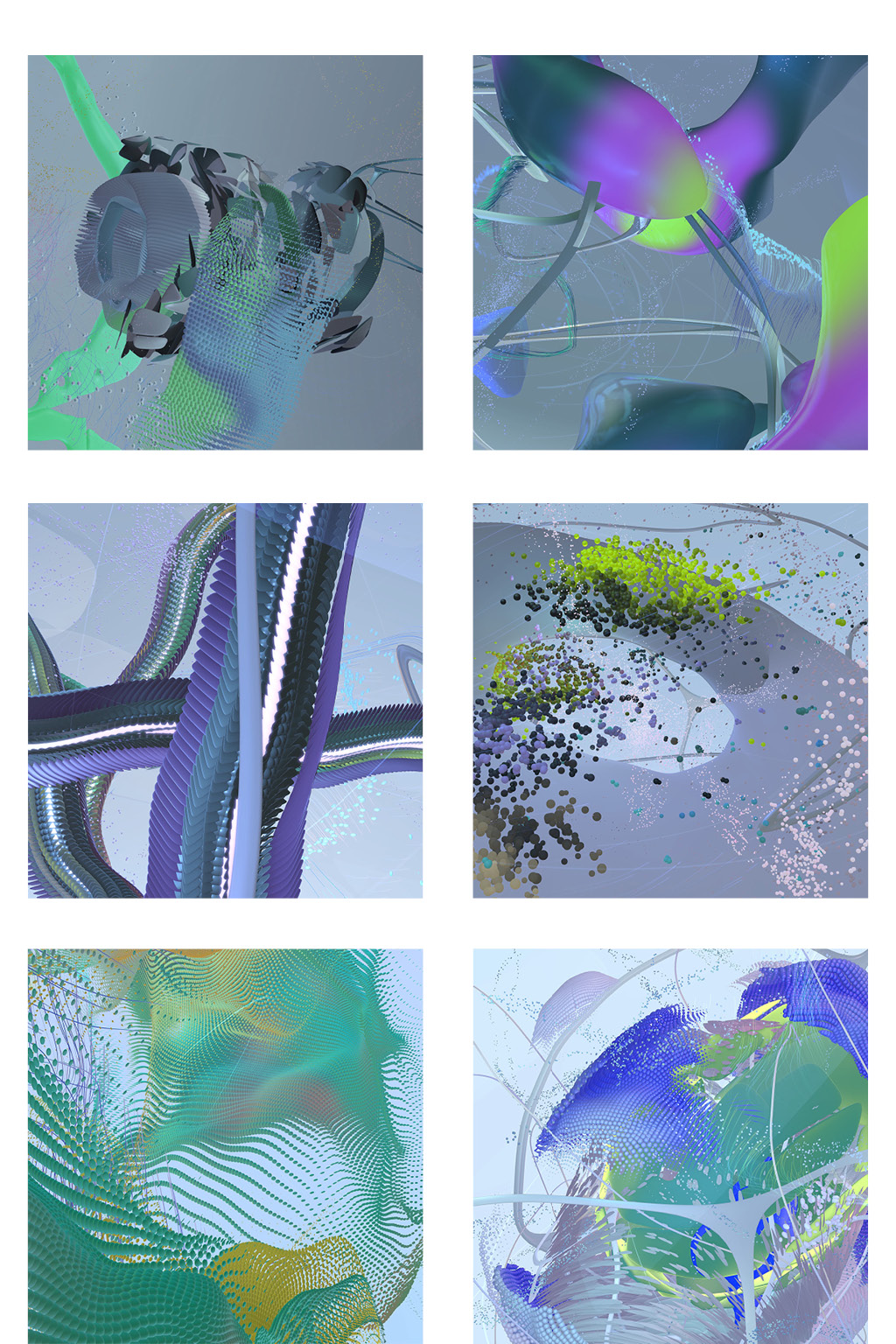

Data Art: Patrick Doan’s “FlowStates” in the ifo Institute

Data expertise meets art. The ifo Institute presents 75 years of expertise with economic data – its collection, analysis and interpretation – in the shape of the data artwork “FlowStates.” And it shows innovative ways of using this expertise to build bridges to society. The result? Forms, seemingly organic, in motion, constantly forming new patterns, flow in time with real data updates across a huge screen in the foyer of ifo’s main building.

The Beauty of Data

Colorful, but discreet, always in motion, seemingly without a beginning or an end – that is how data streams in the guise of abstract visual organisms currently move across the monitor at Poschingerstrasse 5. It is certainly not an everyday sight at the ifo Institute, where economic data tends to be cast in mathematical models and presented in tables, Excel charts, and text. And yet the “FlowStates” installation carries ifo’s DNA within it: It consists of six fixed data series of the ifo Business Climate Index, which are continuously updated and interwoven with data from Eurostat, such as figures on international trade on the European market or production volumes in the construction industry. An algorithm converts the data streams into forms that are presented in a random temporal sequence, determined by a day and night cycle. The result is an interplay between the real flow of data and the corresponding visual translation into movement, form, speed, or color.

“FlowStates” and the ifo Institute

Art is open to the processing of data – and the ifo Institute is open to art. “FlowStates” symbolizes the constant, dynamic change in our economy and society, just as ifo’s research takes up current trends in the economy and society, evaluates them and proposes new options in response. The locally created artwork has an impact, transcends geographical and disciplinary boundaries, and reaches an international audience through digital distribution – just like the Institute’s scientific findings. “FlowStates” underscores the Institute’s commitment to the future of economic research with big data.

For information about the artist, check out the story “The Creator of the ifo Data Painting”.

You can go to the artwork here:

Publications

Elinor Ostrom: A Legacy of Community and Sustainability

Elinor Ostrom (1933-2012), a professor of economics at Indiana University, Bloomington, USA, alongside her husband Vincent Ostrom, was instrumental in founding the so-called Bloomington School. Her work focused on bridging the gap between state and market forces, advocating for efficient, hybrid governance systems. Ostrom championed the principles of self-organization, steering away from centralized state control. The “Elinor Ostrom Villa” at the ifo Institute, adjacent to the main building at Poschingerstrasse 5, honors her Nobel-winning legacy.

Recognition of a Trailblazer: The Nobel Prize

In 2009, Elinor Ostrom broke new ground by becoming the first woman awarded the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences lauded her for demonstrating “how common property can be successfully managed by user organizations.” Her path to this pinnacle was fraught with challenges. Initially, when she secured her first scholarship at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1960, there was skepticism from faculty members who considered it a “waste of scarce resources” to invest in a woman who, they believed, was unlikely to ascend to a professorship.

Such skepticism was proven unfounded as Ostrom’s career unfolded, marked by significant contributions to environmental economics and the study of commons. According to the Nobel Committee, she explored how communities often devise sophisticated decision-making and enforcement mechanisms to avert “imminent conflicts of interest” in managing shared resources, effectively sidestepping the need for dominant state or market interventions.

Her research was concerned with the question of how people organise themselves in order to tackle complex tasks together. She analysed how the rules of institutions affect the actions of individuals who are exposed to certain incentives and have to make decisions. And she presented comprehensive solutions to these challenges.

Sustainable Self-Organization

Ostrom gained international recognition with her seminal work, “Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action” (1990), where she argued that local cooperation, rather than state administration or privatization, often leads to the most sustainable management of commons. Through her global research, Ostrom identified successful and unsuccessful instances of community-based resource management, formulating the “Design Principles” for effective governance. These principles stress the importance of clearly defined boundaries for resource use, collective decision-making processes, and accessible, direct conflict resolution methods.

Wisely Managing Common Resources

The challenge of resource depletion, such as overfishing in oceans, deforestation, and the exhaustion of natural resources, raises the question: Is this inevitable? Advocates of centralized resource management often cite the “tragedy of the commons” to justify their approach. This concept, introduced by U.S. microbiologist and ecologist Garrett Hardin in his 1968 essay, paints a grim picture of communal resource exploitation. He uses a vivid image: a pasture open to all, where each herd owner, motivated by profit, increases their sheep count, leading to overgrazing and eventual ruin. According to Hardin, unrestricted access to limited resources invariably results in their overexploitation, concluding that “Freedom in the commons brings ruin to all concerned.” But Elinor Ostrom’s research uncovered that privatization or centralized government control are not the only paths to preventing resource depletion, highlighting the potential for local communities and resources.

Innovations Beyond Market and State

The assumption that the market is the sole mechanism for managing private goods, and that centralized control is necessary to curb selfish behavior in the management of public goods, is challenged by Elinor Ostrom’s extensive body of work. Her database at the Center for the Study of Institutional Diversity in Tempe, Arizona, contains over 1,000 case studies on the shared use of scarce resources, showcasing a vast array of instances where individuals cooperatively manage resources in environmentally sustainable ways.

One of her earliest field studies in the 1970s focused on groundwater management in Southern California, an area facing the critical challenge of dwindling groundwater reserves amid a growing population. Through her investigation, Ostrom encountered a variety of structures and flexible networks that local municipalities had developed to regulate groundwater extraction. This study uncovered that that the communities in small and medium-sized towns, through necessity, had formed governance structures more adept at addressing the challenges of water management than larger, centralized state institutions.

Learning from Lobster Fishermen in Maine

In the 1920s, the lobster populations off the coast of Maine faced near extinction due to overfishing. This crisis prompted the local fishermen to take innovative steps towards self-organization to preserve their livelihoods and the lobster stocks. They instituted a series of creative rules aimed at sustaining the lobster population. One notable measure was the tagging of pregnant female lobsters before releasing them back into the ocean, ensuring they could continue to contribute to the reproductive cycle. A trader who offered an animal with a tag at a market was ostracized by fishermen and buyers alike. This practice discouraged fishermen from catching these crucial contributors to the lobster population’s regeneration.

This example from Maine and other cases are a testament to Elinor Ostrom’s assertion that complexity in managing common resources does not inevitably lead to chaos. Instead, it shows how localized, community-based approaches can yield sustainable solutions, ensuring the long-term viability of shared resources.

People

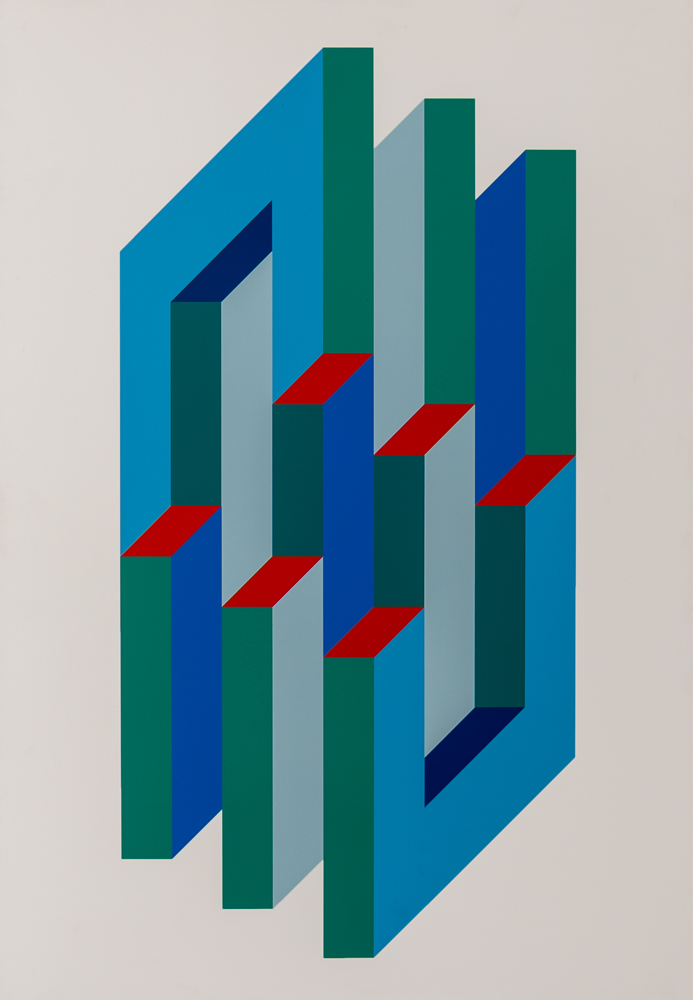

Ernst Helmstädter: Economist and Artist

The vibrant screen prints by Ernst Helmstädter (1924–2018) are a striking feature in the corridors of the ifo Institute. These works were acquired in the 1980s by Karl Heinrich Oppenländer for the ifo, forming a unique connection between economics and fine art. In parallel to his academic career, Helmstädter engaged deeply with aesthetic theories, discovering surprising parallels along the way.

A Distinguished Career in Economics

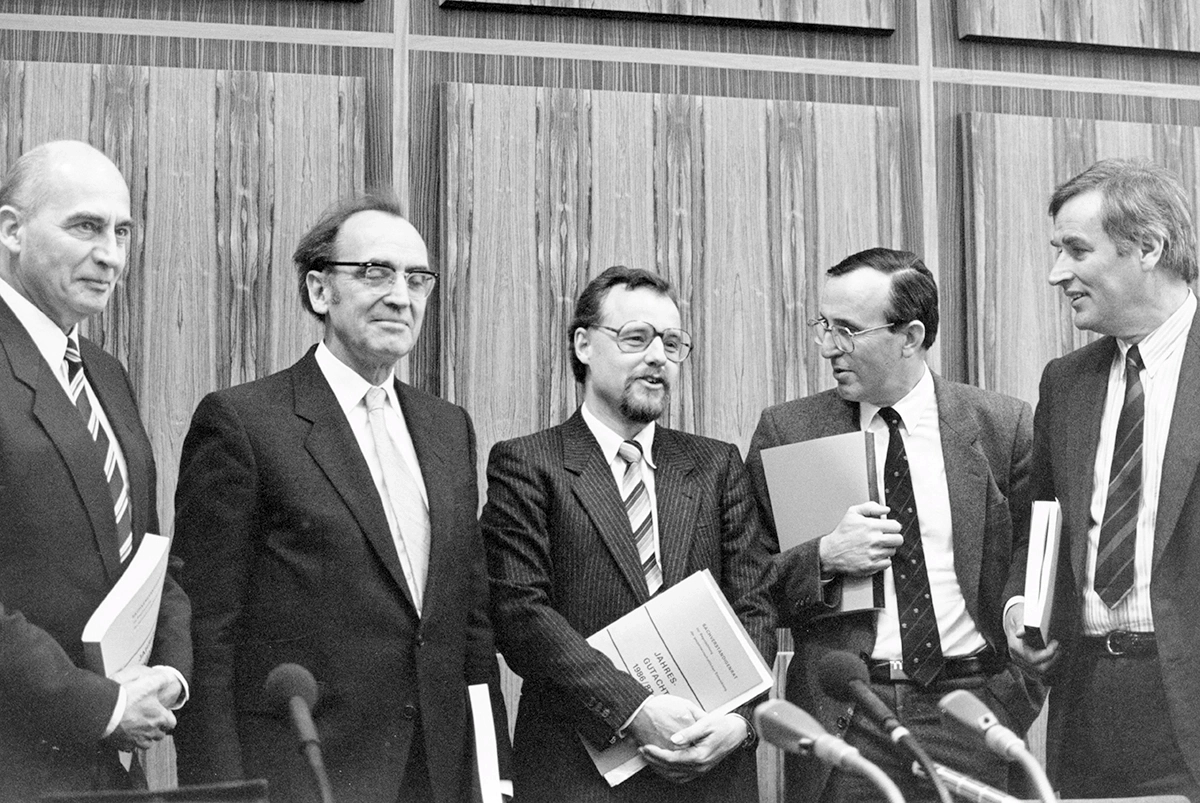

Born in Mannheim in 1924, Ernst Helmstädter studied economics and sociology at the University of Heidelberg, where he earned his doctorate in 1956. After working at the Federal Ministry of Finance and the Federal Office for Economics and Export Control, he became a research assistant at the University of Bonn in 1961, where he later earned his habilitation in 1965. In 1969, Helmstädter was appointed Professor of Economics at the University of Münster, where he led the Institute for Industrial Economics Research and the Research Center for General and Textile Market Economics. Throughout his career, he was active in academic administration and cultural promotion, leading the Senate Committee for Art and Culture in Münster for nearly a decade after his retirement in 1989. Renowned for his research in growth and structural economics as well as distribution theory, Helmstädter authored numerous publications, notably his two-volume textbook “Economic Theory.” He also served on the German Council of Economic Experts from 1983 to 1987.

Helmstädter’s Exploration of Op Art

Op Art, short for Optical Art, is an artistic movement that avoids symbolic meanings and narrative content, instead relying solely on form, color, and structure to create its effects. Through geometric shapes and bold contrasts, it generates illusions of three-dimensionality, movement, and vibration. Artists in the Op Art movement applied the latest theoretical insights and technologies, adhered to strict compositional rules, and saw their work as an aesthetic contribution to the theory of perception.

The 1965 exhibition “The Responsive Eye” at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York marked the beginning of Op Art’s broader recognition. Curated by William C. Seitz, the exhibition featured works by artists such as Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley, and Richard Anuszkiewicz, bringing Op Art principles to a wider audience and establishing the movement as a significant part of modern art.

A pivotal moment in Helmstädter’s artistic development occurred during his 1969 research stay at Harvard University. Here, he deepened his engagement with fine art, particularly with the works of Op Art, which was especially popular in New York at the time. In addition to the works of Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley, Helmstädter was especially influenced by the art of Josef Albers, a key figure in the Op Art movement.

Artistic Career

Helmstädter’s artwork plays with viewer perception, using complex patterns and structures to create dynamic visual effects that appear to move and change. His works reflect an ambivalence in the perception of images, a concept central to both his artistic and economic thinking. To bring his visual concepts to life, he preferred techniques such as carefully crafted collages and screen printing. His artistic creations have been featured in exhibitions in cities like New York, Montreal, and Vienna.

Bridging Art and Economics

The dynamic effects central to Op Art also resonate with Helmstädter’s economic research. Just as Op Art simulates movement and transformation through visual illusions, his economic studies focused on dynamic processes in growth, structural economics, and distribution theory. He often emphasized the inherent ambiguity in interpreting data, a theme explored in perception theory at the time, which found parallels in Op Art compositions. This overlap between art and economics inspired Helmstädter’s own creative works.

People

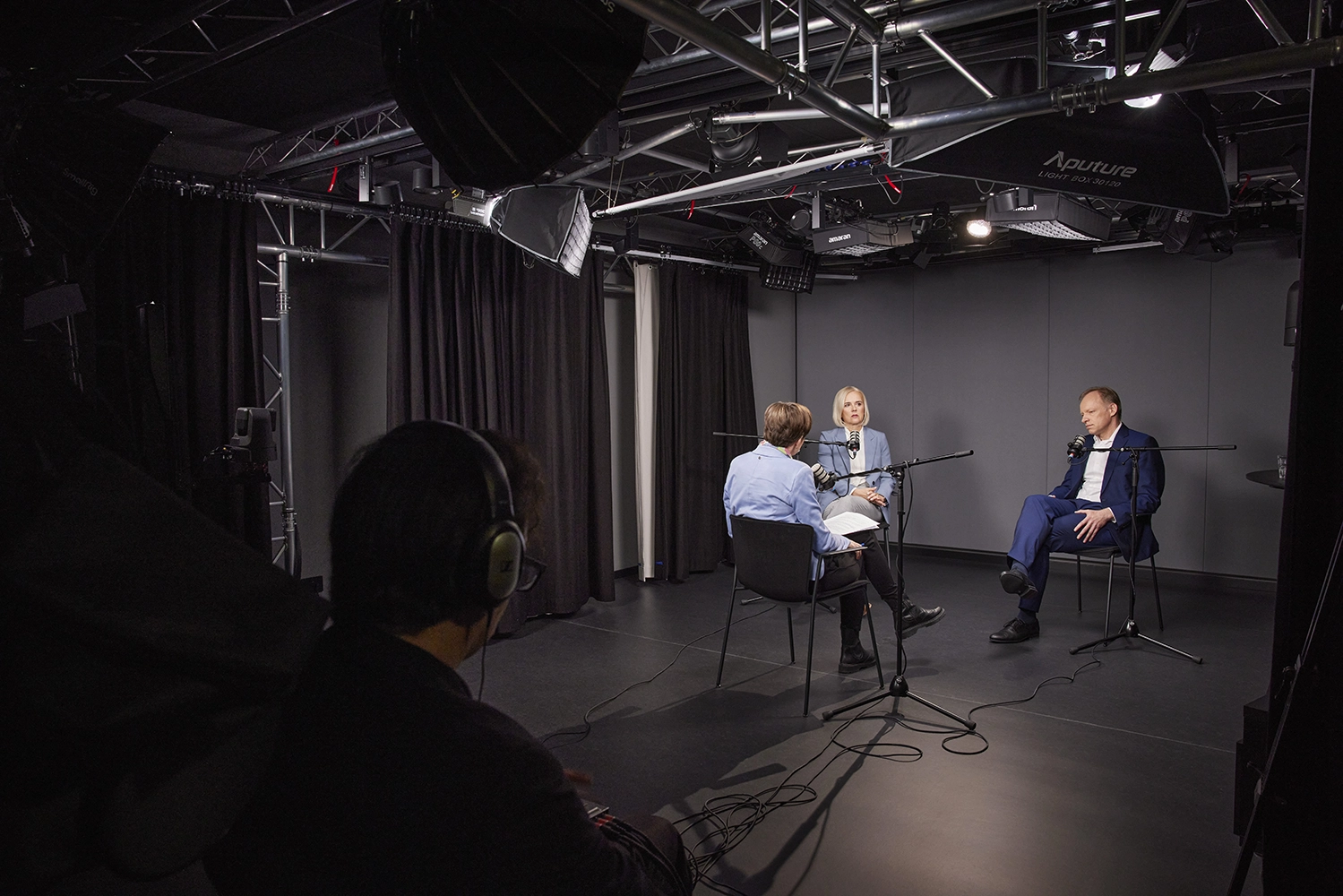

Exploring Dual Leadership: Podcast with Stephanie Dittmer and Clemens Fuest

Can two heads lead better than one? Stephanie Dittmer and Clemens Fuest, co-leaders of the ifo Institute, embody this approach, balancing the scientific freedom and administrative necessities inherent in managing a renowned research institute. Their leadership style, characterized by shared responsibilities, not only fosters a culture of collaboration but also integrates the nuances of managing such dynamic tensions within their organizational framework.

In the realm of research, maintaining independence from political and societal influences while delivering top-notch research poses significant challenges. How does ifo navigate these waters, and what metrics are effective for guiding staff performance?

Tania Lieckweg, a consultant specializing in strategy development, leadership, and organizational growth, sheds light on the efficacy of dual leadership. She highlights the importance of embracing dissent, aligning under a unified strategy, and prioritizing more than just output metrics to ensure leadership success.

This insightful discussion is available in a podcast as part of the series "Die Zukunftsmacher*innen" (The Future Makers) produced by osb international systematic consulting, first released as a "Science Special" in December 2023 (German only).

Impulse

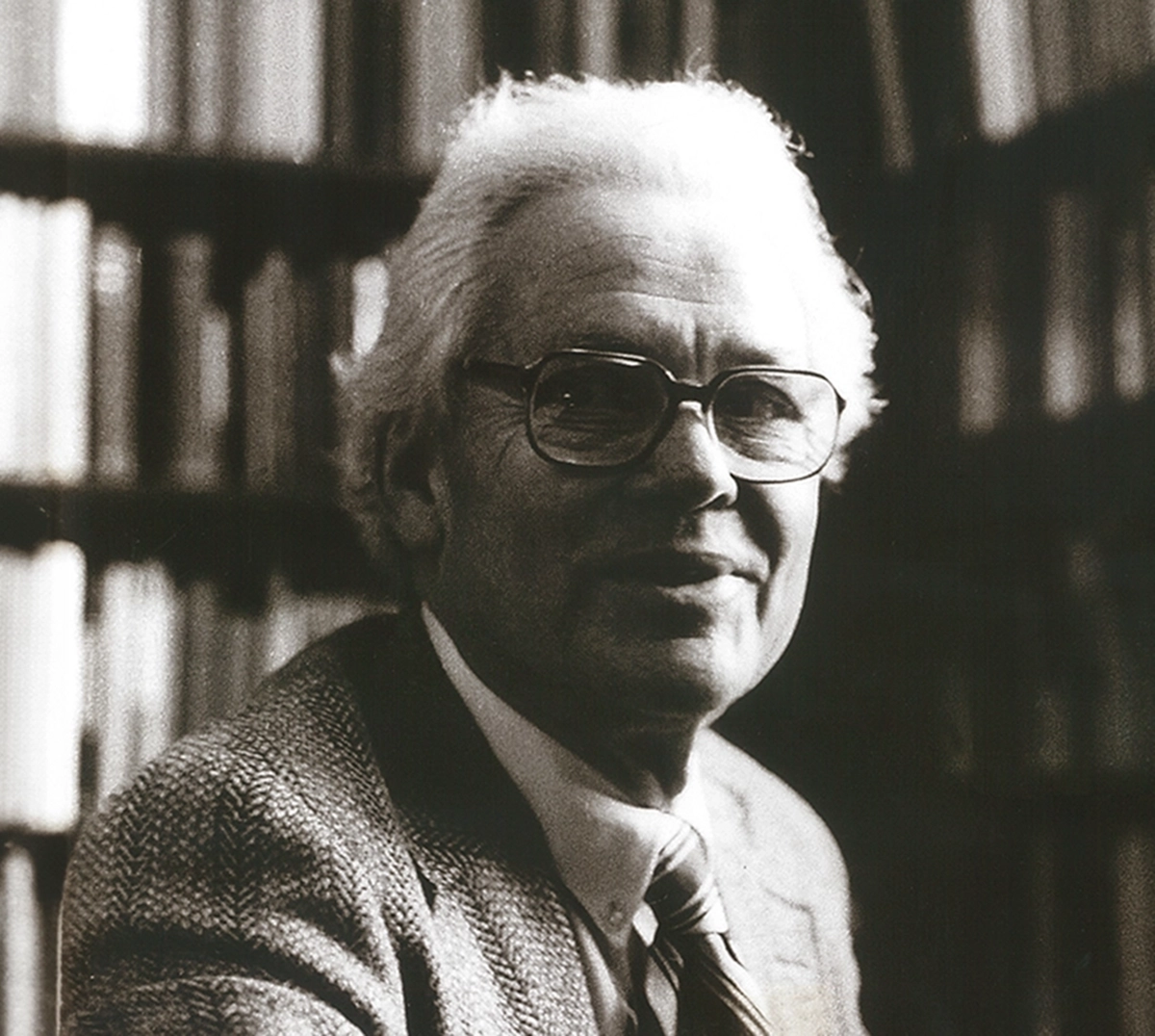

From the White House to the ifo Institute: David Bradford

“David Bradford worked tirelessly and enthusiastically for the ifo Institute. His impartial judgment, wisdom and friendship were a great help.” This is what the ifo Institute wrote in its obituary about the American economist and political advisor David Bradford, who was one of the most important chairmen of the ifo Institute’s Scientific Advisory Council. Bradford died in 2005 at the age of 66. In his honor, the ifo Institute’s main building in Munich was renamed the “David Bradford House” that same year.

An Illustrious Academic and Political Career

David Bradford’s educational journey took him from Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he studied from 1956 to 1960, to advanced degrees at MIT, Harvard University, and ultimately a doctorate from Stanford in 1966. He served as a Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton, and from 1993 at the Law School of New York University. Known as a leading expert in US tax policy, Bradford also held significant roles in government. He was the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Tax Policy from 1975 to 1976 and played a pivotal role in President Ronald Reagan’s tax reforms during the 1980s. From 1991 to 1993, he served as a personal advisor to President George H. W. Bush.

Bradford’s academic contributions significantly shaped public debate on consumer taxation, public goods pricing, urban planning, and environmental policy. A staunch advocate of the 2005 Kyoto Protocol, he was deeply involved in global efforts to combat climate change.

A Quantum Leap in Tax Policy

David Bradford’s seminal work “Blueprints for Basic Tax Reform” laid the groundwork for the sweeping 1986 tax reforms under Reagan, which dramatically reduced the top tax rate from 70 percent to 28 percent, positioning it as the lowest among industrialized nations at that time. His book “Untangling the Income Tax,” published in the same year as the reforms, offered an exhaustive analysis of income tax variations and championed the idea of a consumption tax.

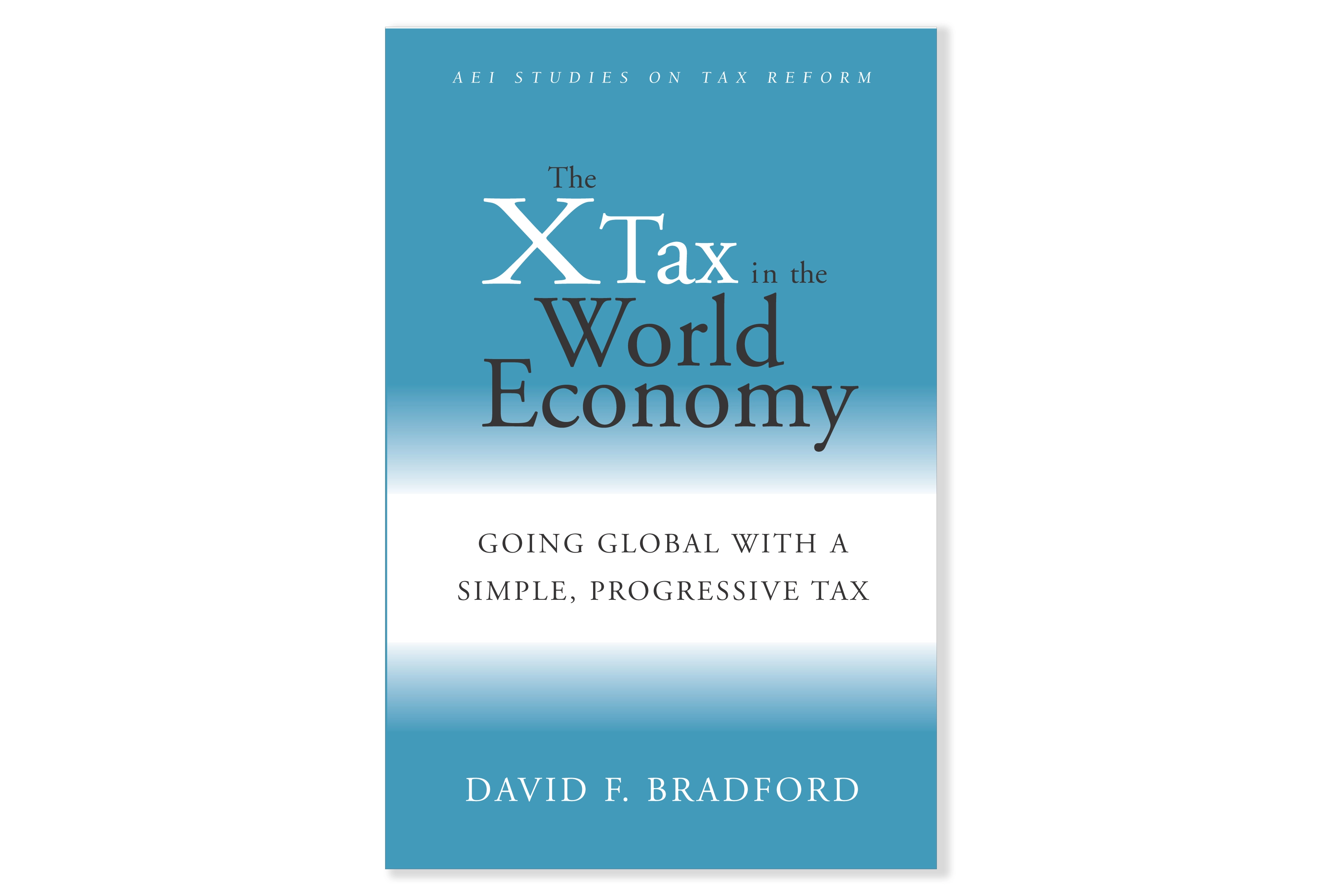

The “X-Tax” Concept

Bradford’s X-Tax proposal sought to simplify and make the tax system fairer through a dual approach: taxing companies after allowing deductions for investments and payroll, thereby incentivizing job creation and innovation; and imposing a progressive income tax on individuals after subtracting private savings and investments, thus facilitating long-term financial planning for families. His vision was to exempt profits from financial transactions from taxes, creating a more streamlined and equitable fiscal environment.

Guiding the ifo Institute’s New Direction

When Hans-Werner Sinn assumed leadership of the ifo Institute in 1999, he faced a period of uncertainty about its future. Under his leadership, the institute’s Scientific Advisory Council was reconstituted, bringing on board twelve new members including Nobel laureate Robert Solow from MIT and David Bradford from Princeton University. After their appointment in May 2000, Bradford was elected Chairman of the Council in September of the same year. Under Bradford’s chairmanship, the Advisory Council played a crucial role in redefining the ifo Institute’s scientific direction, significantly contributing to its ascent as a premier global economic research institution.

People

Hey Teacher – We Don’t Leave You Alone

School is an important place to acquire skills in the field of economics. Teachers are ambassadors: They have a significant influence on what students know and think about the economy. In times of fake news and an overabundance of information, the ifo Institute sees it as a central task to be a credible and reliable source of economic information for teachers and their students. To this end, we have a well-coordinated portfolio of offers, which we implement partly on our own and partly in cooperation with established partners. Partners are the Association of Bavarian Business Philologists (wpv) and the Dillingen Academy for Teacher Training and Personnel Management (ALP).

Bringing research into the classroom

The ifo Institute views teacher training and continuing education as a means of keeping business educators up to speed with information, preferably firsthand, on current research and debates. To this end, we launched the ifo Hands-On Modern Economics Teaching Days training series in 2018. It is aimed at economics teachers from Bavaria at general education and vocational schools. Since 2019, the Center for Economics Education in Siegen (ZöBiS) has been providing additional support for teaching the contents of this advanced training course, which is conducted in cooperation with the wpv.

Every spring, 25-30 teachers are guests at the ifo Institute for two days. ifo President Clemens Fuest presents a current economic policy topic to discuss with the teachers. ifo business surveys and economic forecasts are also a fixed part of the curricula. The presentations also take into account current developments, such as inflation.

Other contributions include foreign trade, energy, and taxes. At the same time, the needs of the teachers are also surveyed. One result of the needs survey was the introduction of our teacher newsletter, the ifo Klassenzimmer (classroom).

New impetus for teachers

The ifo Klassenzimmer newsletter provides teachers five times a year with current information grouped by topic for lesson preparation. It contains both opinion pieces by ifo experts and research articles on a specific topic and supplements these with data and editable graphics. Another special perk ifo offers teachers is a protected area on its website, where they can access all the newsletter content.

Since 2018, we have also been offering a training initiative together with the ALP that focuses on the practical implementation in classrooms of economic policy research results. For the annual event, the ifo Institute provides the specialist speakers, while ALP provides the premises and organization . The event is a useful addition to ifo’s own offerings as a way of reaching teachers in other parts of Bavaria.

Economy as competition

Since the 2018/19 school year, our researchers and subject specialists have been involved in YES! (Young Economic Solutions). This national and now largest school competition on global challenges in the economy, society, politics, and the environment for grades 10+ is a joint project of the Leibniz Information Centre for Economics (ZBW) and the Joachim Herz Foundation under the patronage of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action.