In 1990, Chancellor Helmut Kohl made a bold promise to transform the regions of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony-Anhalt, Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia into thriving landscapes where people would want to live and work. Despite these aspirations, even three decades after the Berlin Wall came down, the economic vitality of former East Germany remained markedly below that of the West. The ifo Institute’s Dresden branch has been tracking this structural transformation since 1993.

Merging Economic Landscapes

The Berlin Wall’s fall in 1989 paved the way for the State Treaty on Economic, Monetary, and Social Union in July 1990, heralding the economic merger of Germany. The Deutsche Mark became the national currency across both East and West Germany, extending the social market economy’s principles to the newly incorporated federal states. This transition placed immense pressure on East German enterprises to adapt quickly. The Treuhandanstalt, a public agency tasked with privatizing over 12,000 state-owned businesses, failed to find buyers for about 3,000, leading to their closure. To stave off an economic downturn, the federal government launched the “Gemeinschaftswerk Aufschwung Ost” (Joint Initiative for East Germany) in 1991, introducing the solidarity surcharge among other tax increases to fund this support.

Economic Progress Since 1989

By the late ’80s, East Germany’s economy lagged in competitiveness. The conversion rate between the GDR Mark and the Deutsche Mark was unfavorably high. Overnight, West German laws took effect in the East, further straining its struggling economy. “Looking at East Germany’s economic trajectory from the initial years post-reunification, the strides made are impressive,” notes Joachim Ragnitz, Deputy Director of the ifo Institute’s Dresden branch. Following reunification, East Germany saw a significant population decline due to lower birth rates and mass emigration, reducing the population by over 2 million since 1991 and those of working-age by more than 10 percent.

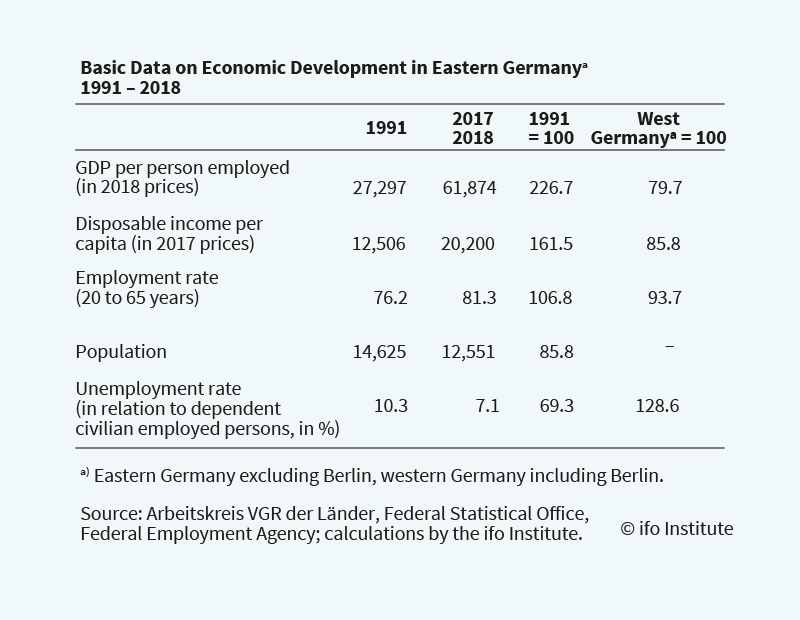

Yet, by the end of 2023, unemployment had drastically fallen from highs of around 20 percent to just 7.1 percent, after having averaged 7.6 percent in 2018. Economic output, risen by 127 percent, real disposable income, risen by 62 percent, and job numbers per working-age individual had seen substantial increases by 2018.

Comparison with the West

Residents of the eastern states often measured their progress against the West, feeling dissatisfied despite considerable advancements. Economic output and wages in the East only reached about 80 percent of the West’s average, with disposable income just catching up to the levels of Bremen and Saarland.

“Public perception of wage disparities fuels discontent,” Ragnitz explains. In 2018, the median wages for full-time workers in the East were 79 percent of those in the West, partly due to structural differences, such as a higher percentage of workers in low-wage sectors, 38.1 percent in the West and 42.9 percent in the East, and a scarcity of large corporations in the East, affecting overall wage averages.

Addressing Structural Shortfalls

Three decades post-reunification, East Germany had only managed to match West Germany’s economic output from the mid-80s. Persistent structural challenges – like fewer large firms, limited headquarters presence, a shortage of skilled professionals, and reduced research and development activities – continued to impede the East’s growth. “Considering these challenges... it’s notable that the East has managed to keep pace with the West’s economic growth in recent years at all and not falling further back,” Ragnitz points out. He suggests that the general sentiment might be gloomier than the actual circumstances, advising politicians to navigate beyond perceived public moods.