The economic reconstruction of Europe post-World War II was intrinsically linked to renewed efforts towards European unification. This vision took a concrete shape with the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 by France, Germany, Italy, and the Benelux countries. This marked the initial step to-wards creating a common European economic area, laying the groundwork for the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957. The ifo Institute provided in-depth analysis throughout this process, closely monitoring the unfolding integration.

Challenges Along the Way

The journey towards integration wasn’t without its hurdles. In 1954, the proposed European Defense Community (EDC) stumbled due to a veto from the French Na-tional Assembly, highlighting the complexities of aligning not just economic but also military and political interests across nations. A pivotal moment came in 1955, when the stalled unification efforts were revitalized by focusing on economic collaboration based on the successful model of the ECSC.

Strategic Economic Discussions

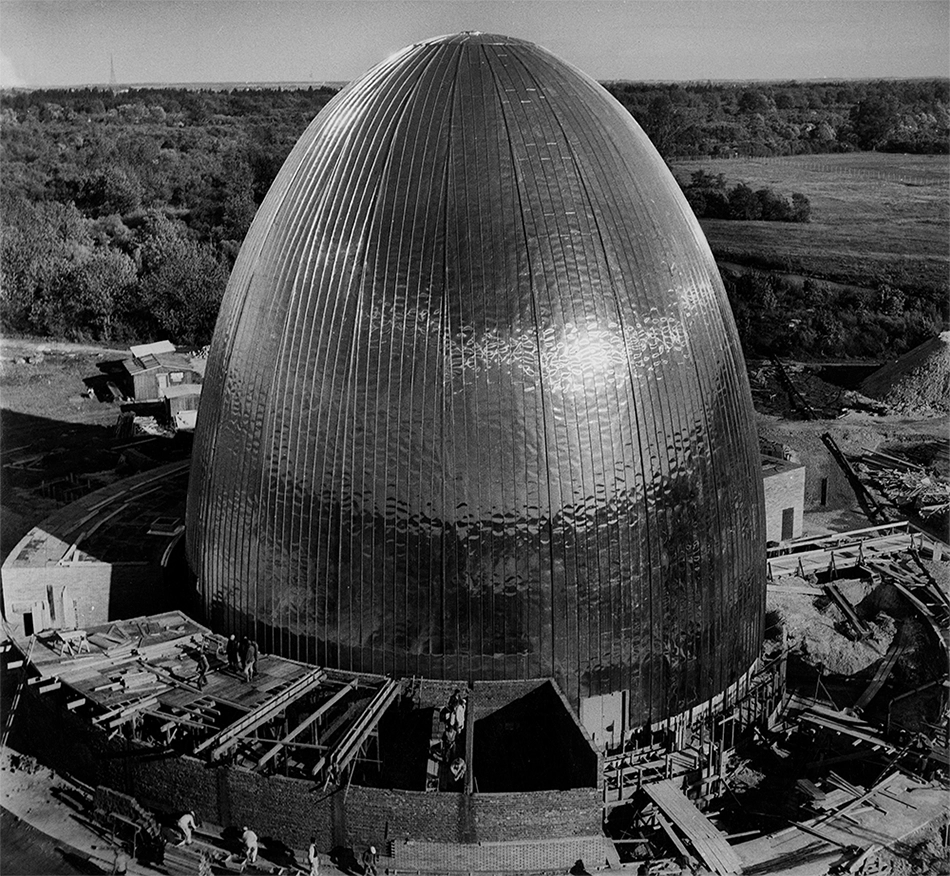

The revival of integration efforts gained momentum at the Messina Conference in 1955, where ECSC members convened to discuss a new economic community. The conference, led by French Foreign Minister Jean Monnet, who was instrumental in proposing the economic unification, also prioritized cooperation in the nuclear sec-tor, seeing the peaceful use of nuclear energy as a key component of their collective progress.

Formulating the Common Market

The “Spaak Commission,” named after Belgian Foreign Minister Paul-Henri Spaak and set up as a result of the conference, developed recommendations that formed the basis for establishing a common market. This market was envisioned to encom-pass free movement of goods, services, capital, and people, alongside a common agricultural market and a unified European trade policy. These initiatives were aimed at eliminating customs barriers and quotas, thereby fostering a more integrated Eu-ropean economy.

Significant Milestones in Rome

On March 25, 1957, the six founding states signed the Treaties of Rome, establishing the EEC and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM). These treaties, which came into effect on January 1, 1958, were seen by German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer not just as economic agreements but as pivotal political instruments aimed at furthering European political integration through economic collaboration: “The Common Market must be seen not primarily as an economic treaty, but as a political instrument. It must be seen in conjunction with the Council of Europe, the Coal and Steel Community and EURATOM; in short, it is a series of political facts. The EEC is essentially a political treaty, the purpose of which is to achieve the political integration of Europe by means of economic commonality.”

The ifo Institute’s Role and Perspective

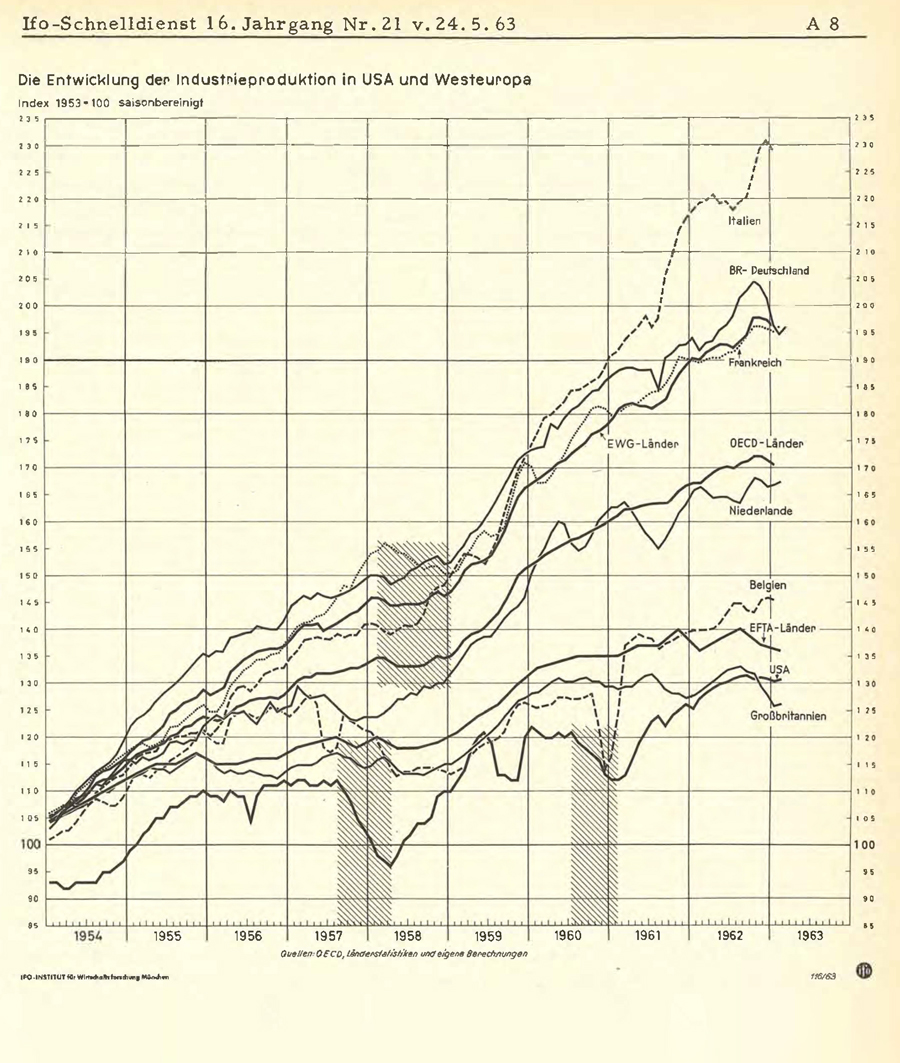

From the beginning, the ifo Schnelldienst, a publication of the ifo Institute, covered various facets of European cooperation, starting with discussions on meat produc-tion within the EEC in 1957. From 1961 onwards, the focus broadened. As the EEC’s Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs sought to standardize official statistics and introduce industry surveys, ifo was tasked in 1961 with implementing these surveys in Western Germany. Closely based on the ifo tendency surveys, the European Business Survey was published monthly from spring 1962 onwards and was carried out in around 14,000 industrial companies in the European Economic Community. An annual investment survey was added somewhat later. The results of both surveys have been published regularly in the Schnelldienst since 1963.

A Critical Voice Amidst Economic Optimism

While the EEC was generally viewed positively, the ifo Institute maintained a critical stance, questioning the direct correlation between the EEC and economic upturns in member states. This skepticism was articulated in the Schnelldienst on May 24, 1963, arguing that while economic integration contributed to growth, the real drivers were the intrinsic economic strengths of member countries like France, Italy, and West Germany. The ifo’s objection to the generally positive assessment of the effectiveness of the new economic community, was based on the institute’s own surveys, which intervened in the public debate with fact-based arguments. Even today, develop-ments and policy decisions in the EU are a strategically important field for the ifo Institute and for the political platform EconPol.