In a glowing recommendation letter from November 1953, Oskar Anderson highlighted the impressive grades with which Hildegard Harlander, then 43, had completed her economics studies. Further endorsed by Adolf Weber, Harlander successfully joined the ifo Institute in 1954, where she remained a key figure until her retirement in 1975, despite being denied a traditional career trajectory.

From Bookstores to Breakthroughs in Economics

Born on November 9, 1910, in Heilbronn, Harlander initially trained as a bookseller and worked as an interpreter before pursuing economics at the University of Munich in 1933. After her engagement in 1935, she broke off her studies. Her two sons were born in 1939 and 1946. Looking back, she considered dropping out of university a mistake and wrote: “In the Third Reich, women were pushed out of the professions.” Her marriage ended in divorce in 1951. As a single mother who soon had to return to work, Hildegard Harlander was a rare exception in the early post-war years.

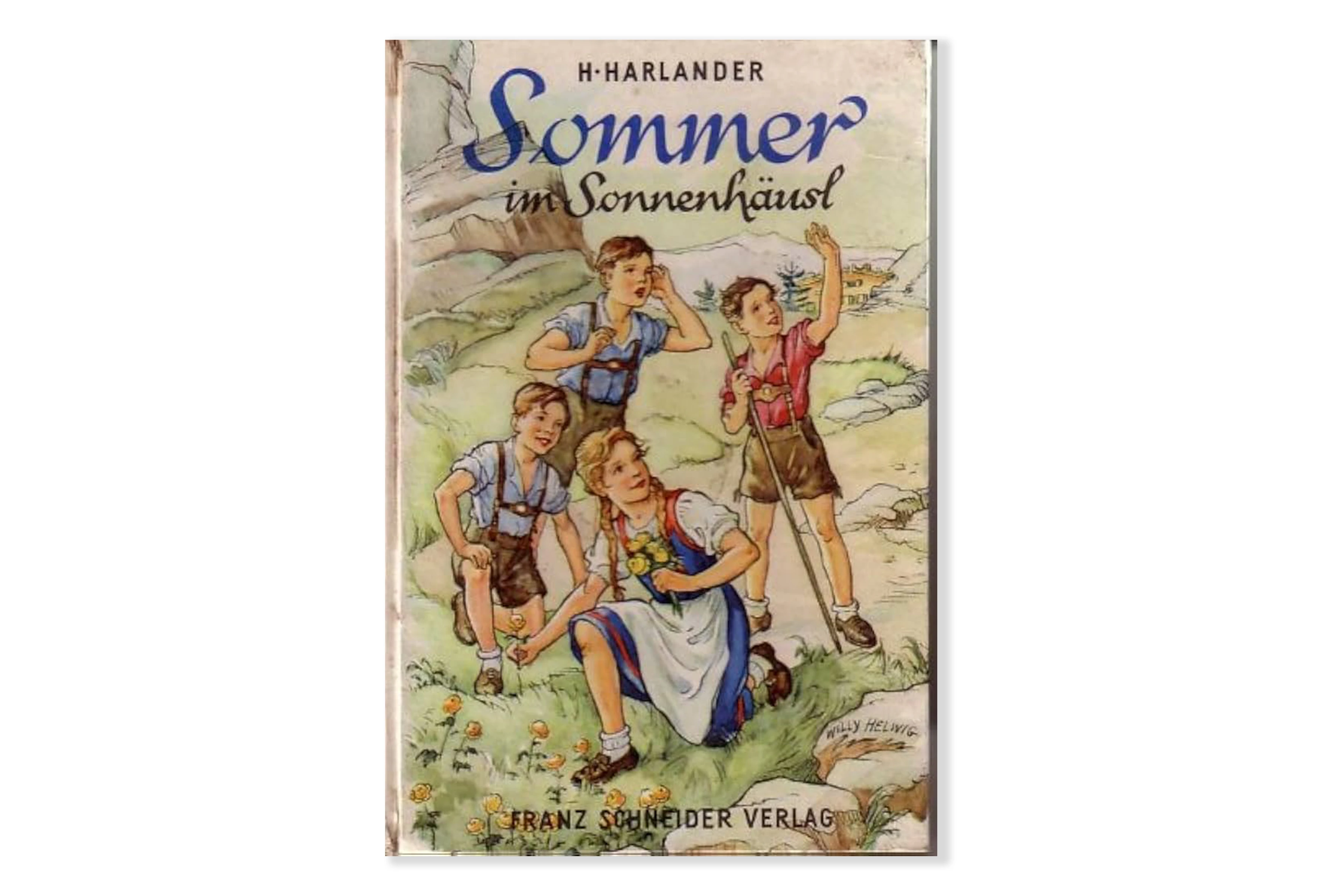

Summer in the Sonnenhäusl

Hildegard Harlander decided to resume her studies. She returned to university in May 1952, completed the remaining seminars by October 1953, and passed her exams in the same year. To fund her studies and support her family, Harlander drew on her passion for the outdoors, authoring two children’s books inspired by her extensive hikes in Austria’s “Loferer Steinberge.” Published by Franz Schneider Verlag in 1950 and 1951, Bei uns im Sonnenhäusl and Sommer im Sonnenhäusl enjoyed several reprints, contributing financially during her academic pursuits.

From Munich to East Africa: Expanding Research Horizons

Hildegard Harlander was hired by the ifo Institute on January 1, 1954, as an assistant to Hans Langelütke and found herself as one of the few women in a scientific community dominated by men. She took part in important conferences and meetings and wrote reports and minutes as secretary. Over time, she became well-versed in all areas of research at the institute. In 1961, when the Fritz Thyssen Foundation agreed to finance a multi-year project to research the economic situation in East Africa and the scientific basis of an appropriate development policy, Hildegard Harlander undertook her first trip there with Hans Langelütke and two colleagues from the Board of Directors. Here she found a field that matched her interests perfectly. From July 1965, she was able to devote half of her working hours to the “Africa Study Unit” headed by Wilhelm Marquardt at the ifo Institute and researched the role of women in the economic and social development of East Africa with great commitment. In 1966, she spent two months visiting the continent’s major research institutes, and in 1971, together with her colleague Dorothea Metzger, published a study with seven case studies on African development banks.

Environmental Expert from the Very Beginning

In April 1971, Harlander authored an important internal study titled “Problems of Environmental Protection,” offering a pioneering look at the then-nascent issue of environmental sustainability. She provided a comprehensive review of scientific and political discussions on environmental pollution and energy, highlighting her foresight and analytical prowess. Above all, however, she had the courage to bring attention to this pressing issue, which at the time was not yet being taken seriously by the wider scientific community – including at the ifo Institute. In contrast, she recognized early on the challenges that the environment would pose for those responsible in politics and business in the future.

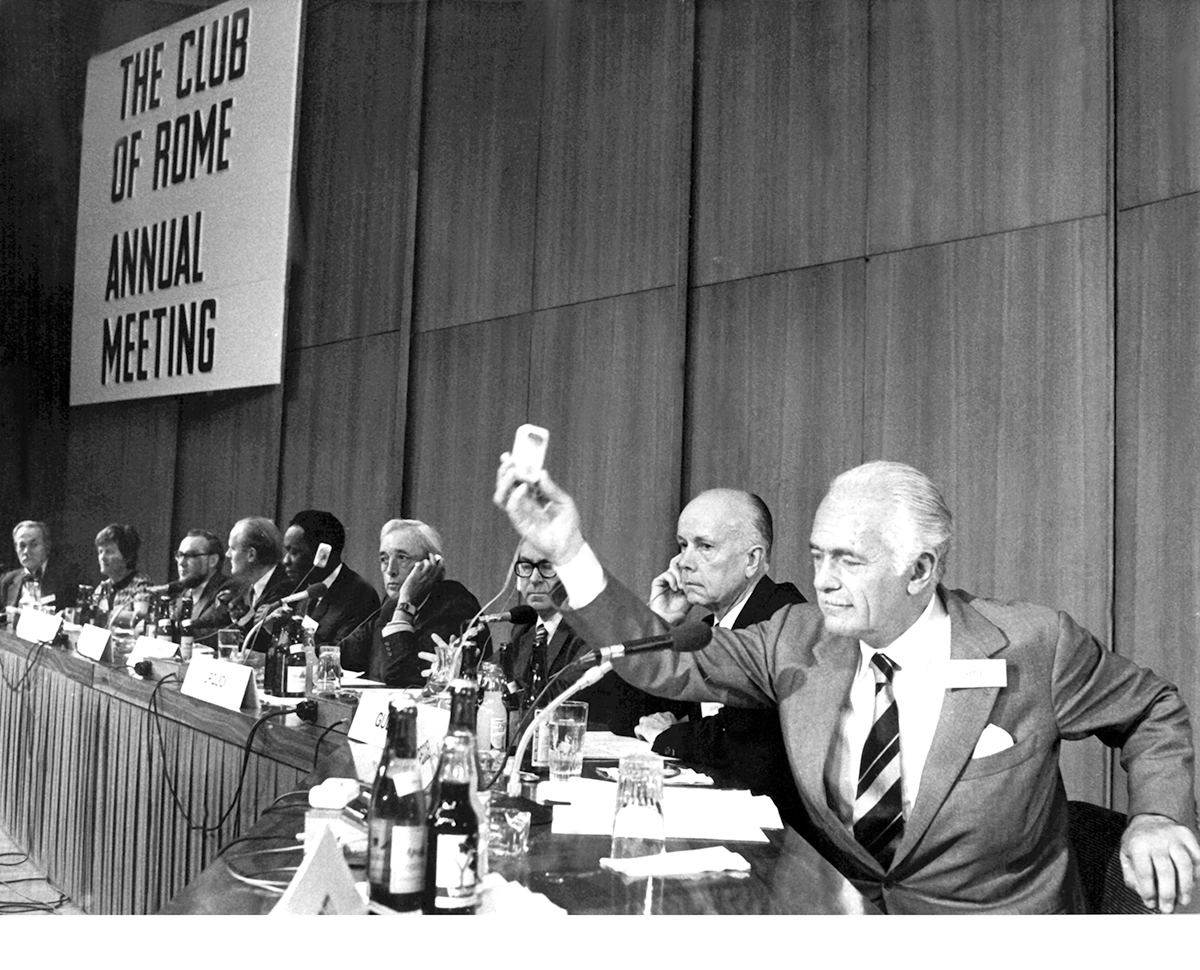

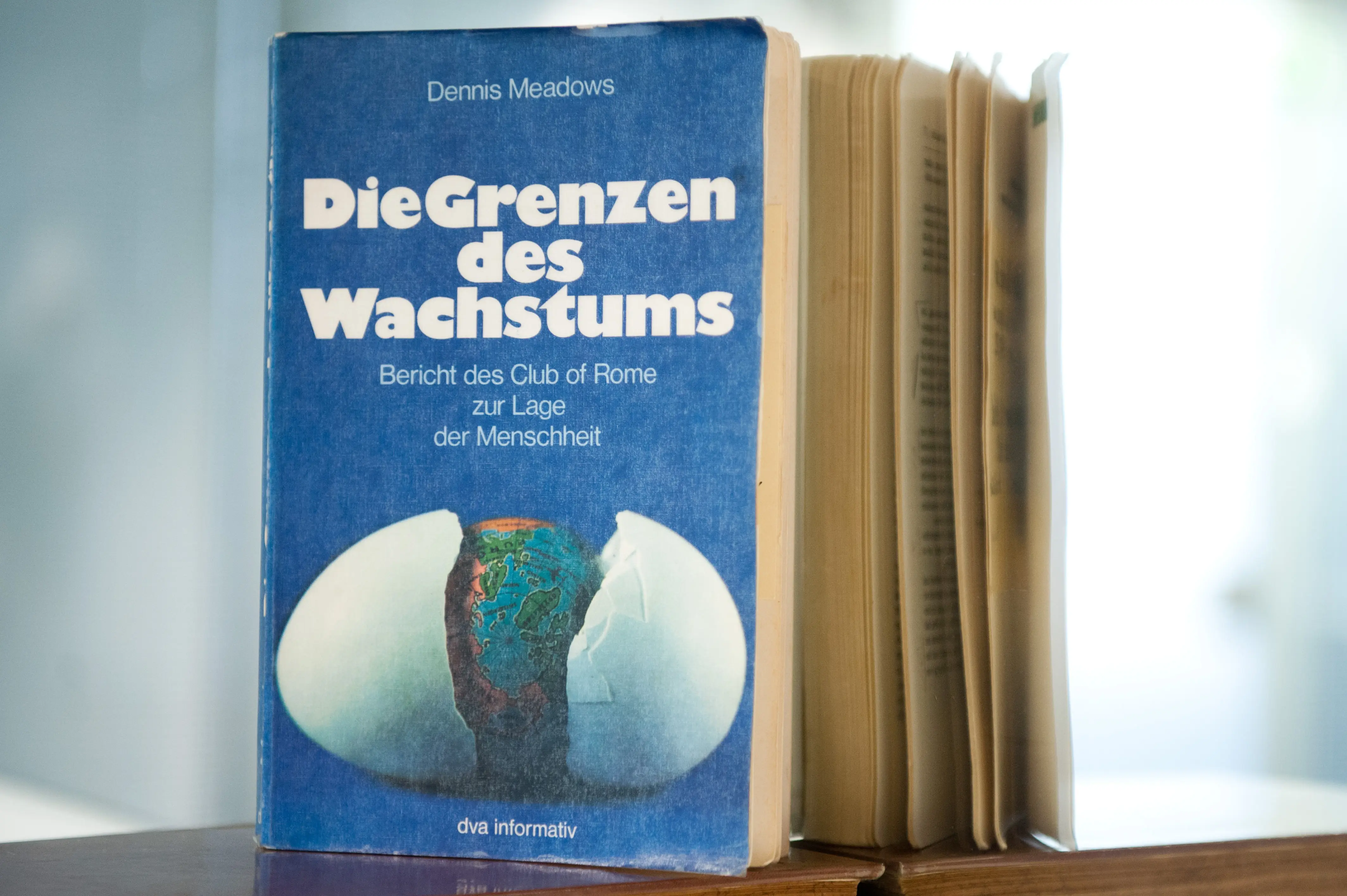

“Not a dolce vita organization” – The Club of Rome

Less than a year later, in March 1972, she reported on the study “The Limits to Growth,” a founding document of the environmental movement, which had just been presented by the Club of Rome. In her conclusion, she argued against the claim derived from the study that only an immediate abandonment of the growth principle could save the world. In contrast, she took a pragmatic stance: why not react to the long-term perspectives set out in the study with short- and medium-term decisions and thus gain time to “demonstrate meaningful chances of survival and the possibility of their realization with new models?”

In February 1973, Harlander summarized the unusually broad response to the Club of Rome’s study. She was interested in “why many economists, of all people, reacted so unusually allergically and aggressively.” She suspected a fear of new scientific horizons: “Economic research puts so much effort into short-term (economic) analysis and forecasting and obviously neglects long-term perspectives.” This is where economists could benefit from the study because it made it clear to them “that they need to broaden their horizons, namely in terms of subject matter to an interdisciplinary view, in terms of time to a longer-term perspective, and in terms of space to global connections.”