The ifo Institute was born from the union of two pioneering institutions in January 1949. The merger of the Süddeutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung and the Informations- und Forschungsstelle für Wirtschaftsbeobachtung created a hub that has profoundly influenced economic policy and research for over seventy-five years. How did this merger come about? Let‘s take a look at the complex history of the ifo‘s foundation.

The Genesis of Practical Economic Research

The story begins in 1925, with the founding of the Institute for Economic Observation of German Finished Goods at the Nuremberg School of Commerce by Wilhelm Vershofen, around the same time as the Institut für Konjunkturforschung (IfK), now known as the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), in Berlin. Ludwig Erhard, who later became a pivotal figure in German economic policy, joined this Nuremberg institute in 1928, contributing significantly to its development, especially in industrial market research. After facing a career setback in 1942 by being denied a succession at the head of the institute, Erhard established his own institute, laying the groundwork for future endeavors.

From Economic Research to Political Influence

Ludwig Erhard’s career was a blend of academic prowess and political acumen. Following World War II, as U.S. troops entered his hometown of Fürth on April 19, 1945, Erhard quickly aligned himself with the American military authorities, offering his expertise as an economist. By October 1945, he was appointed Minister for Trade and Industry in Bavaria. His roles within the economic frameworks of post-war Germany, including his leadership in preparing for the currency reform and his position as Director of the Economic Council of the Bizone in March 1948, were instrumental in shaping his path to becoming the first Minister of Economics in Adenauer’s government.

Bridging Science and Practice

The “Institute for Industrial Research” founded by Erhard in 1942 became the “Institute for Economic Observation and Economic Consulting” (from 1946) and in 1947 the “South German Institute for Economic Research.” Erhard’s vision was clear: he believed that non-university economic research institutes should serve as bridges between academic research and practical economic and state applications. He soon used the metaphor of the “bridge” that an economic research institute had to build between university economic research on the one hand and state and economic practice on the other. This vision was rooted in a commitment to non-partisan, scientifically rigorous work that directly engaged with the challenges and opportunities of post-war Germany.

Challenges and Merger

Despite its ambitious beginnings, the South German Institute for Economic Research faced financial difficulties by 1947, struggling to secure the necessary funds for expansion. Erhard and his colleagues had relied on private-sector support, but without public funding, the future of the institute was uncertain. Simultaneously, another economic monitoring institute, initiated by Karl Wagner at the Bavarian State Statistical Office, was expanding its capabilities. Together with Hans Langelütke, Wagner continued to expand the information services in the field of economic observation at the State Office from April 1948, before bundling them into the “Information and Research Center for Economic Observation” (ifo). This institute began conducting company surveys immediately after the currency reform and launched the “Ifo-Schnelldienst” in 1948, which became a critical resource for economic data.

The Formation of the ifo Institute

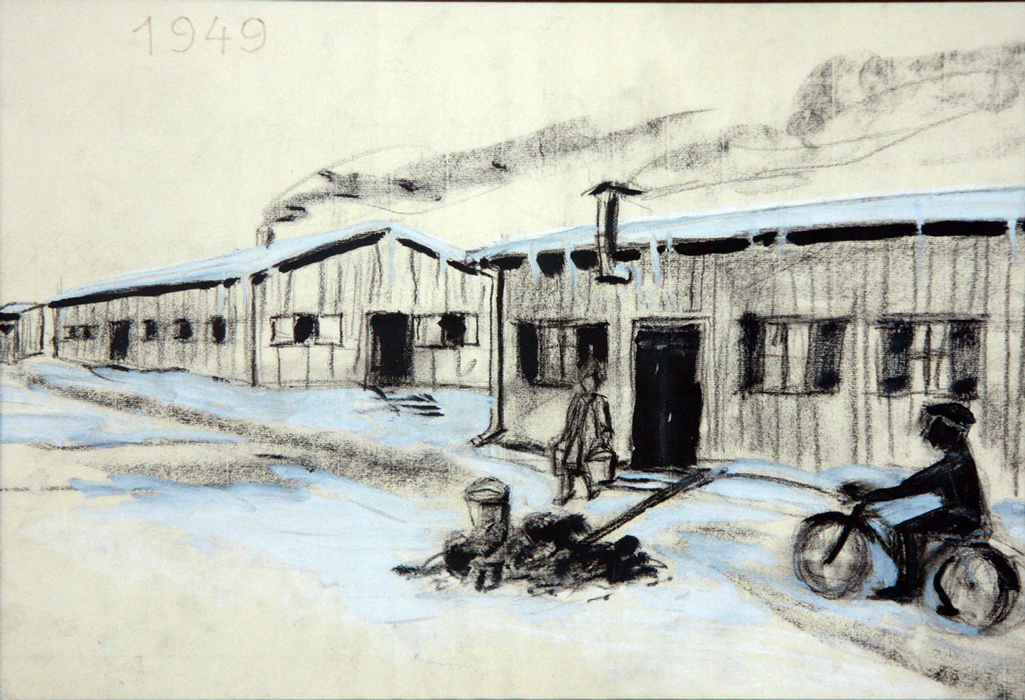

The Bavarian state government, recognizing the potential of consolidating resources, encouraged the merger of these two institutes. On January 24, 1949, the agreement was signed to form the Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung e.V. München – shortened to the ifo Institute. Starting its operations in March 1949 with specialist departments in economics, industry, and business administration, the institute quickly established itself as a leader in applied economic research, despite the modest beginnings in makeshift barracks. The Bavarian State Statistical Office provided the institute with some rooms in the buildings at Rosenheimer Strasse 130 – a former, partially bombed-out police barracks – as an interim solution. Most of the staff were housed in two wooden barracks on the former parade ground of the barracks.

Note: For the sources used in this text, click on the imprint.