Herzogpark, nestled in the Bogenhausen district of Munich, serves as the picturesque locale for the ifo Institute’s headquarters. This elite residential enclave, steeped in cultural and intellectual history, has been a fertile ground for what is now an internationally acclaimed economic research center.

Founding of a Prestigious Neighborhood

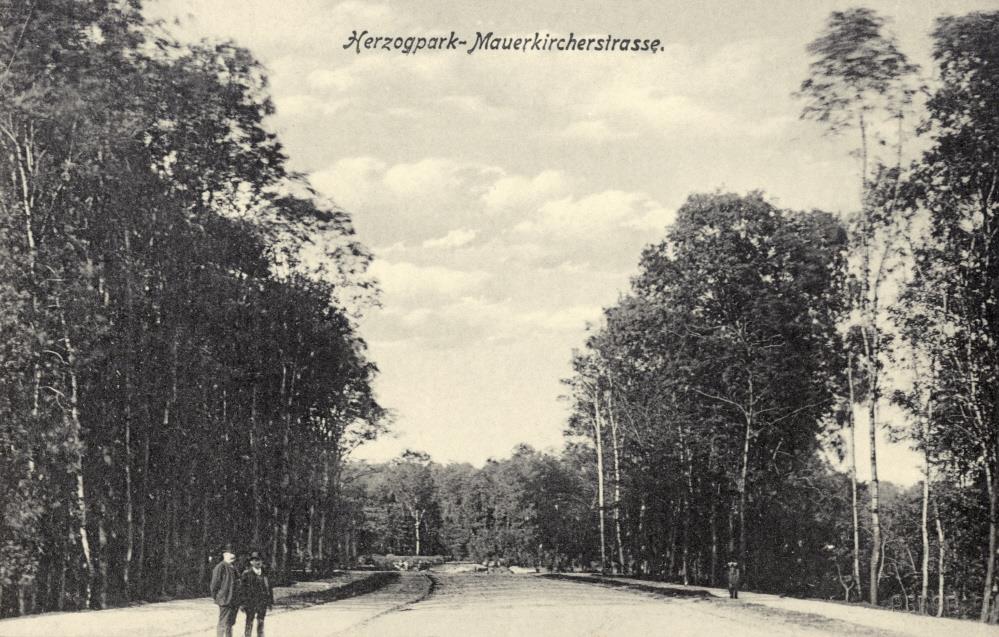

Herzogpark is named after its original owner, Duke Max in Bavaria (1808-1888), the father of the later Empress Elisabeth of Austria, known as Sisi. His son, Archduke Karl Theodor, sold the expansive land along the eastern banks of the Isar River to the Terrain-Aktiengesellschaft Bogenhausen-Gern in the early 1900s. At that time, the duke's former hunting grounds were still wild, untouched nature, an impression of which is conveyed in Thomas Mann’s story “Herr und Hund.” The new development area was initially opened up by a long main street named after the Archbishop of Passau, Friedrich Mauerkircher, and later, the parallel Pienzenauerstraße was laid out, named after a Bavarian noble family. During World War I, construction was halted, and many plots along the streets of Herzogpark, often named after famous poets from Gellert to Stifter, remained undeveloped for a long time.

In the nascent days of Herzogpark, pioneers of art and intellect carved out a space where creativity and thought flourished. Ludwig Freiherr von Gumppenberg-Pöttmes-Oberprennberg, an early settler, established his residence in a grand villa at by 1906, signaling the area’s burgeoning appeal to Munich’s cultural elite. Across from him, Alfred von Heymel, a luminary in the literary world, set roots at Poschingerstrasse 5 in 1909, marking the area as a magnet for creative minds. The enclave also attracted figures like Robert Hallgarten, a scholar with a keen intellect, and his wife, Constanze Hallgarten, a stalwart in women’s rights and peace activism, who together contributed to the area’s intellectual vibrancy. Notably, Thomas Mann, seeking a conducive environment for his family and work, and Bruno Walter, a maestro with a passion beyond the podium, chose Herzogpark for its serene yet stimulating atmosphere. They were joined by Erich Marcks, a historian and Bismarck biographer, setting the stage for a neighborhood rich in dialogue and discovery.

Expansion and Cultural Flourishing

As Herzogpark’s reputation as a haven for the arts and intellect grew, it drew a wider circle of notables. The actor duo Herta von Hagen and Gustl Waldau, celebrated for their contributions to the stage, made their home here, adding to the neighborhood’s artistic flair. Ludwig Ritter von Zumbusch, a professor at the Academy of Arts renowned for his child portraits, moved into a villa designed by architect Otto Riemerschmid at 9 Schönbergstraße in 1910. The arrival of Leopold Stokowski, a friend and peer of Bruno Walter, underscored the area’s appeal to musical virtuosos. This period also saw Thomas Mann, celebrated for his literary work, moving into the notable Villa at Poschingerstraße 1 in 1914. Bruno Frank, another torchbearer of literature, along with the distinguished banker and bibliophile Otto Deutsch-Zeltmann, member of the “Society of Munich Book Lovers” and the Maximiliansgesellschaft, found in Herzogpark not just a home but a community of like-minded individuals. It was here too that Adolf Weber, an economist who significantly influenced the direction of economic research and policy in Germany, his involvement with the “Economic Working Group for Bavaria” and meetings held in his home in Herzogpark contributed to the foundational ideas that continue to inform the work of the ifo Institute.

A Place of Intellectual Exchange

The ifo Institute itself found a home in Herzogpark thanks to a tip from Adolf Weber about the building at Poschingerstrasse being for sale post-World War II. Starting in 1952, the institute’s staff worked here and later occupied spaces within Herzogpark’s iconic triplet villas, cementing the institute’s success story in an area renowned for its intellectual legacy. Today, the ifo Institute’s buildings still echo the vibrant intel-lectual and cultural history of Herzogpark and its esteemed past inhabitants.